Big money versus small farmers

| By winter oak on August 9, 2024 |

Number 95

In this issue:

- Big money versus small farmers

- The two-way mirror of oppression

- Fanfare for Anarchism: A Home for the Homeless

- Renaud Garcia: an organic radical inspiration

- Acorninfo

1. Big money versus small farmers

A war is being waged on small farmers by a combination of Big Business and the state, a campaigner from Brittany, France, has warned.

In an interview with the journal La Décroissance, farmer and author Yannick Ogor explains that the weapon being wielded is that of regulations, supposedly intended to protect animals and punish bad husbandry.

In particular he describes the “traceability” being imposed by the authorities – farmers have, for instance, to identify a new calf within seven days of its birth and transmit the information to the state.

He says: “This ‘traceability’ is the central plank of agricultural policies aimed at ‘preventing health risks’ and ‘guaranteeing the quality of meat’.

“The majority of the public support it on the understanding that it allows better control of our food and to slow down the industrialisation of agriculture.

“But, in actual fact, it does exactly the opposite! It is the open-air farms that find themselves in difficulty: it is more difficult for them to deal with traceability than in factory farms where everything is controlled”.

Ogor adds that the authorities can sometimes come down very hard on farmers who don’t tick the required boxes.

He cites the case Jérôme Laronze whose four-year dispute with the state over the “traceability” issue led to the authorities arriving to seize his herd and to him being shot dead, in the back, by armed police, in 2017.

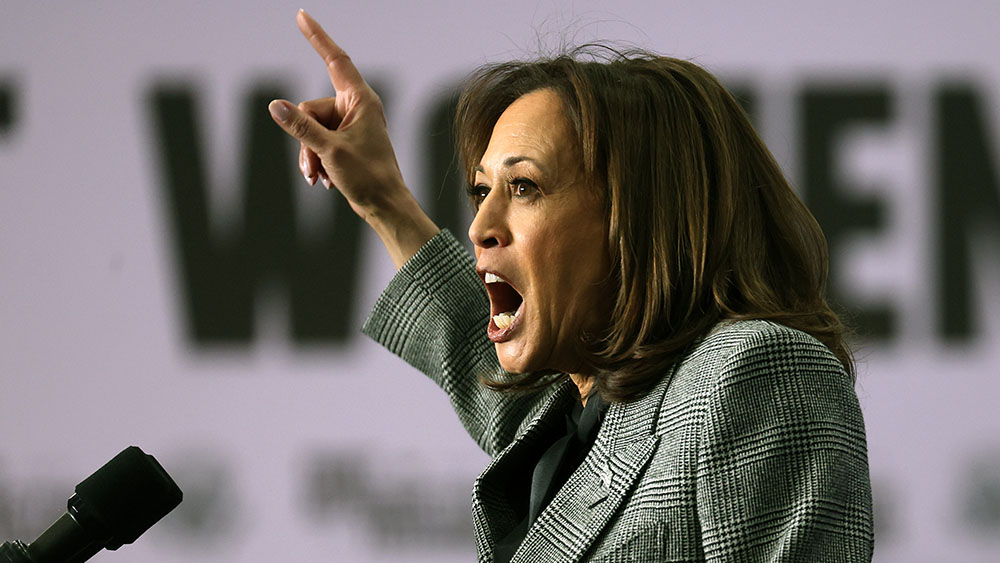

Laronze’s death sparked widespread anger and protests, such as the one pictured at the top of this article.

A further scandal surrounds the fate of those animals that are confiscated by the state because of failure to comply with regulations, explains Ogor.

They are given to animal welfare organisations like the OABA (Organisation pour l’Amélioration du Bien-être Animal), ostensibly to live out their lives in happy “retirement”.

But, in reality, such bodies cannot manage to keep them for very long and end up selling them for meat.

“And the money from the sale of their herds goes not into the farmers’ pockets but into those of the animal organisations and of the dodgy dealers who deal with the sale,” adds Ogor.

“Under cover of protecting animals and the public, farmers are truly being robbed – ruined by administrative punishment”.

The left has generally not taken up this issue, blinded by its love of state control into wrongly imagining that the regulations are a good thing and are targeting industrial agriculture.

The state’s “biosecurity” agenda also disproportionally affects smaller, more traditional farmers, since their open air livestock are in contact with wild animals that are supposed to spread diseases.

Ogor insists that these illnesses are really caused by the growth of agro-industry: constantly breeding animals with the sole aim of producing more meat has weakened their immune systems.

Furthermore, packing them closer together encourages the spread of sickness, as does the fact that they are transported all over the world.

The interviewer concludes by asking Ogor if this was a question of a class war waged on small farmers by the rich, whose only interest is in economic growth and profit.

He replies: “Who are the directors of the OABA? Big business leaders, veterinary surgeons, highly-ranked government officials, and so on.

“It’s the French elite telling the ‘country bumpkins’ how to do things. It’s crucial to keep that in mind.

“The official emphasis is on maximised economic growth and export results, in support of the big supermarket groups. And that is what certain environmentalists, and the left, are supporting”.

Yannick Ogor has just brought out a short book on this issue, entitled Abattages à la ferme. Info via Editions Quartz, BP 8, 23260 Crocq, France.

2. The two-way mirror of oppression

by Paul Cudenec

“Two-way mirror” must be one of the more misleading terms in the English language.

It is defined by my dictionary as “a half-silvered sheet of glass that functions as a mirror when viewed from one side but is translucent from the other”.

It is therefore not so much two-way as doubly one-way, both in terms of its role as a mirror and as a window.

The most obvious use of this one-way/two-way device is to spy on people.

Behind what appears to be an ordinary mirror in a hotel or an interview room hide people who are watching what is going on without their victims’ knowledge or consent.

If one imagines this spying device as horizontal, rather than vertical, it makes an excellent metaphor for the society in which we currently live.

Up above sit those who designed the “mirror”, watching from the translucent side every last movement made by their prey.

Down below are those pour their life energy into increasing the wealth and power of the parasite class.

All they see above them is a mirror, which seems to confirm that their little prison-world is all that there is.

If sometimes they find their lives slightly unpleasant, unhealthy, unnatural and restricted, this is, they tell themselves, a reflection of something that simply exists, by itself, and for which they have to accept their fair share of collective responsibility.

It’s “today’s society” or that person or party voted into power where they live.

If more general factors are identified and blamed, these will be apparently “neutral” phenomena such as a “pandemic”, “climate change”, “terrorism” or some other vague “threat”.

Because, when they look up, they see only the mirrored side of the glass, they are incapable of seeing that the things they don’t like are being deliberately inflicted on them by a hidden group of rulers.

Even the idea that there could be any such people, behind the mirror of society, will not enter into the minds of many.

So this horizontal mirror acts against our interests in, appropriately enough, two ways.

It allows the ruling mafia to spy on every detail of our lives and it hides that same mafia from view.

There are no two ways about it, some mirrors are meant to be smashed!

3. Fanfare for Anarchism: A Home for the Homeless

by Darren Allen

Occasionally you hear people complain about being ‘politically homeless’. What they tend to mean is either that there is no longer a traditional left-wing, which sought to manage people and nature in the name of a global ‘society’, or that there is no longer a traditional right-wing, which sought to subjugate people and nature in the name of a national ‘tradition’. The reason they’ve departed from political life is that in our neoliberal, postmodern, online unworld, society no longer exists, the Western working class has been either weakened or subsumed into the [decaying] middle-class and nations are now irrelevant, as are institutions, so there is no place left for either the ideology of the traditional management class (socialism) or for the traditional owner class (capitalism), and this has left those who still adhere to them, ‘homeless’. While such people remain blind to the true nature of the postmodern condition — a consequence of technocratic capitalism and technocratic socialism — they will be unable to even consider the only home that can ever welcome them; Anarchism…

I say ‘perennial’ because, as I have argued in an introductory article, nature is anarchist, friendship is anarchist, work is anarchist (when the boss is absent), romantic love is anarchist, scientific endeavour is anarchist, all primal (pre-agricultural, pre-conquest) societies were anarchist and artistic creation is anarchist. Life itself is anarchist, which explains why anarchistic forms of sociality surface again and again, throughout history, even in the teeth of the most oppressive social conditions imaginable. Anarchism springs up in prisons, in shanty towns, in peasant communes and even occasionally, and most amazingly, in the modern workplace. Anarchism sprouts through the cracks of the system as weeds do between its paving stones, because it represents the root and spring of our social nature.

You would think then that anarchism would be a popular way of life today. You would think that a movement which in essence includes all great artists and scientists [1] would be extremely attractive. You’d think that a genuine alternative to the system-friendly managerialism of the left and the system-friendly capitalism of the right would be an easy pitch. You’d think that an approach to politics which, like the majority of populations everywhere, pushes leftwards economically (redistributing wealth) and rightwards socially (enforcing organic cultural borders), would find a great deal of popular support. You’d think! But I’m afraid you’d be wrong, for two basic reasons.

Firstly, most people do not want the spiritual and intellectual freedom that anarchism represents. It terrifies them. They want to avoid the crushing oppression of worldly life, but they cling to the institutions, the money, the capital, the comfort, the routine, the technology and the mindless work that are all preconditions of that life. What they are seeking is not freedom from systemic confinement, but reform within it — a better run prison, with nicer guards, cosier cells and some power within it to push other prisoners around. Generally speaking, those on the left seek power through management (and through knowledge), while those on the right seek power through property (and through violence), [2] but nobody seek freedom from a system in which one cannot survive without such power, which is why the institutionalised inmates of our world all unite to crush genuine movement towards such freedom. [3]

We all love a rose in the garden, we love look upon its elegant form and to

inhale its gentle fragrance, but nature is not, in the first instance,

a rose in the garden, it is a trillion weeds on the motorway verge.

Everyone knows, instinctively, that anarchism represents the truth, which is why critics never directly address it (preferring to destroy it, ignore it, laugh at it or offer peripheral objections [4]) and why they colonise its surface form. This is the second reason anarchism [5] is not popular, because it has been, like every other word which can express the truth co-opted, by traditional leftists (socialist thinkers—so called ‘anarcho-syndicalists’ like David Graeber, Noam Chomsky and, less seriously, Russell Brand), postmodern leftists (mainstream anarchism today is essentially a genderless, reasonless, borderless bastion of identity politics), the criminal underclass (the scrags that tend to accumulate in squats [6] and shelters and who naturally gravitate to an ideology that seems to be against everything), and even, believe it or not, capitalists (the laughable oxymoron of ‘anarcho-capitalism’).

It’s not unlike being an outsider. In a decadent society on its last legs, nobody fits in, nobody belongs; which, naturally enough, everybody takes pride in. The quickest way out of feeling unpleasantly cruel, weak or fearful is to be proud of being a sadist, a weakling or a coward; and so it is with feeling lonely, bored, atomised and alienated — it’s easier to enjoy the idea that you’re a rebel than to actually rebel. [7] Thus, the pose of genuine dissent only ever goes so far, never extending beyond the subgroup that one belongs to, one’s church (including the church of atheism), one’s political affiliation (including the ideology of neutrality) or one’s hobby set (including the popular pastime of being interested in nothing), which critical censure never seriously interrupts, as evidenced by the fact that the most ‘rebellious’ writers and artists never seriously jeopardise their popularity with their own readers.

Groupthink extends far beyond such localised affiliations though. A deeper, far more terrible conformity binds a much larger group — humanity itself — which, no matter how conspicuously its constituent nations, factions and institutions conflict, no matter how diverse its individuals appear to be, rests upon a single, selfish foundation, a sad, selfish, miserable omniself, which, when prodded, responds with the same egoic fear and violence. The same unconscious emotionality, the same fear of ridicule, the same anxiety at being alive, the same wilful unhappiness, the same proud stupidity, the same mediocre craving for stimulation or attention. The same, the same, the same. And this featureless, domesticated monoself knows it’s the same, which is why it so desperately reaches out for a reason to seem different, a rebellious badge it can wear that sets it apart from the unhappy mass it secretly knows it is part of.

The free individual is as rare in the world as the wild animal — and his fate is the same — which is why the one political ideology which addresses the free individual, anarchism, is hated, feared and co-opted, made to look like a rather more exciting version of democratic socialism, with much gladness, tolerance, body-positivity, pacifism and play, but all under the roof of a technocratic institution, or compelled by a pitiless capitalist economy. Anarchism, as an honest proposition, will never be presented to people as it is, as a natural principle, common to us all, or as a profound and inspiring philosophy of existence — far deeper than mere politics — and it will never be accepted by a domesticated mass.

But it doesn’t have to be, for, ultimately, anarchism is not a proposition. It is life itself, the social expression of nature. It does not therefore need to be argued for, organised, voted for, pushed or promoted. Put your feet up! Like nature, anarchism will emerge by itself when the conditions for doing so allow it — is already emerging, reaching through the cracks in the pavement of the system. True, this is very difficult to see, in the winter of our world, when visible culture is as dead as the wilderness we crave. But for those who have learnt to look under the surface, life still seethes, even in the wasteland. Even here, in this little room, the day has come.

[1] Yes, all of them, but by ‘in essence’ I mean when they are at their most creative — not necessarily in their political opinions, or lack thereof. Many anarchists rarely discuss politics or social theory and the like, and have no interest in them at all.

[2] And everyone, left and right, seeks power through prestige, or fame, but all this power and comfort tends to make people feel guilty, which is why their prisons must have charities, welfare and the like.

[3] The most famous case in recent history was the Spanish anarchist revolution of the 1930s which was slaughtered by the nationalist right and asphyxiated by the republican / communist left. The situation was similar in the Russian revolution, but you don’t need to journey into history to find cases of the left and right uniting to prevent even the slightest movement towards genuine independence. This is why socialists and capitalists alike tend to oppose home schooling, for example, or self-medication, or genuine self-governance.

[4] Again, see… https://expressiveegg.substack.com/p/anarchism-at-the-end-of-the-world

[5] In some respects using the word ‘anarchism’ is misleading, given the fact that it has been co-opted and given the fact that, etymologically, the word ‘anarchism’ — society without leaders — is rather misleading, when anarchists societies have, and must have, leaders and laws. This is why I offer the term ‘primalism’, to distance the heart of anarchism from its various corrupted forms. But what position would we be in if we had to rewrite every perverted word we use? We’d be speechless. No bad thing, in a sense, because anarchism, being synonymous with life, really requires no word at all to describe it. We only really need to use the word ‘home’ when we’re homeless.

[6] I’m referring here to the typical British squat. I’ve lived in inspiring, well-organised, socially diverse squats.

[7] Another analogy is the co-option of basic decency. Everyone knows that it is morally wrong to be fundamentally selfish, which is why everyone, no matter how abominably, laughably, ridiculously self-obsessed they are, tells themselves that they are fundamentally selfless, honest and fair. It can boggle the mind to hear moral cowards and monsters justify themselves in this way, until you grasp that basic decency has to be co-opted by those without it.

4. Renaud Garcia: an organic radical inspiration

The latest in our series of profiles from the orgrad website.

“In this world of artifice, going beyond the surface to a deeper level, that of the sheer essence of things, is no longer conceivable”

Renaud Garcia (1981-) is a contemporary anti-capitalist philosopher and writer who has voiced strong criticisms of the ideological direction taken by the modern left.

He caused quite a storm (1) in France in 2015 when he warned in his book Le Désert de la critique (2) that certain postmodernist strands of thinking were diverting left-wingers into a dead-end of disempowerment and irrelevancy.

Their deconstruction of reality went well beyond the anarchist insight of denying fake concepts which were used to deceive and dominate – such as “property” or “law” or “nation”.

Postmodernist “leftism” questioned instead whether the entities or structures which exploit and dominate us even exist.

Garcia said that if one accepted Michel Foucault’s claim that power relations existed everywhere, “it becomes illusory to suppose the existence of a subject which has not already been included in these power relationships, in other words a ‘human nature’ whose universal characteristics allow us to imagine an emancipation from repressive power”. (3)

In his 2018 book Le Sens des limites: contre l’abstraction capitaliste, (4) Garcia argued that the artificiality and abstraction of life under contemporary capitalism was dragging us further and further away from a real sense of being alive – in our bodies, in our daily lives, in our environment.

A new call had to go out to humankind, he wrote, particularly to its youngest generations, warning of this debilitating loss of contact with physical reality and demanding another way of living.

This could come from amongst radical environmentalists and anti-industrialists and “from the best of the anarchist and unorthodox Marxist traditions”. (5)

Garcia described our Western world as “a civilization with money as its universal mediation” (6) in which capitalism “encloses” and privatises all aspects of life.

It could not tolerate the idea of anyone living outside of its enclosure, hence its need to stamp out the practice of “subsistence” farming, where communities have the cheek to simply produce enough food for their own requirements, rather than for the requirements of the capitalist profit-machine.

Capitalism forced people into its system by giving them no choice, he explained: “Declaring war on subsistence means dissolving the autonomous ways of life of thousands of people and thereby enslaving them to commercial needs which they can only fulfil by going out to earn a wage”. (7)

Garcia also devoted an important section of his book to condemning the capitalist concept of “work”, which it tries to persuade us has always been a “natural” part of human life.

He pointed out that this was not at all the case: “It only came into existence, as a basic social function, when the capitalist system consolidated and expanded, at the turning point of the 17th and 18th centuries in England”. (8)

The primacy of “work” in our modern society devoured any deeper sense of existence and purpose, said Garcia.

“‘What do you do in life?’ This familiar question, which is supposed to be the first point of contact with another person, says a lot about the place that work takes in our lives. It reduces the individual to what he does in life, thus supposing a central role for work, which fills the otherwise neutral space of life”. (9)

Garcia echoed Ferdinand Tönnies (with his contrast between communal Gemeinschaft and commercial Gesellschaft) in drawing a distinction between what he called “vital praxis”, an individual’s effort and contribution to the community, and “abstract work”.

He explained that “work”, in this latter capitalist sense, was not about actually doing something useful or creative. It was just about spending a certain amount of hours in paid employment, the value of which was irrelevant. It was purely about quantity (of hours, of money) rather than about quality.

Garcia wrote that he regretted that so many on the left remain fixated with the capitalist fetichisation of work and even regarded it as central to their anti-capitalist struggles. This, he concluded, was “a blind spot for the whole of traditional Marxism”. (10)

He argued that it was pointless to merely point out the contradictions of capitalism, while remaining attached to the excessive optimism regarding technological progress that was essentially itself part of capitalism.

He declared: ” If we want to develop a critical theory of society which is not content with mere adjustments to the centre of the system of producing goods (defending ‘jobs’) or on its fringes (through a more quality-orientated form of economic growth) then we will definitely need to imagine going beyond work. This aim might well seem utopian, but it is also precisely the most realistic way of escaping from the false life of this economic abstraction”. (11)

The idea of defending a natural world which included human communities’ relationships with the environment, had been neglected by Western anti-capitalism, he said, particularly under the influence of mainstream Marxism.

Uprooted from our previous rural existences, we today often found ourselves living in a sterile and life-denying suburban sprawl, a space created “for the demands of capital”, where people were trapped in a dependence on their cars and thus on the oil industry. (12)

In Le Sens des limites, Garcia also echoed William Morris’s critique of the artificiality of industrial capitalism: “In this world of artifice, going beyond the surface to a deeper level, that of the sheer essence of things, is no longer conceivable”. (13)

In place of this, he proposed, like Morris, a different, socialist, world, where quality rather than quantity was the guiding principle: “Opposed to the world of having, this world of being will differ from it in the same way that a cultured eye differs from a vulgar eye, a musical ear from a non-musical one, a stiff and clumsy body from a supple and graceful one, a finely developed sense of taste from one brought up on the quick sensations of ersatz industrial food”. (14)

Garcia dedicated another section of the book to examining, and condemning, transhumanism, which he termed “the official ideology of technological capitalism”. (15)

This ideology “reduces the human brain to a simple processor of information, a mere calculating machine” (16) and is built on the “basic negation of the reality of living organisms”. (17)

Behind it lurked a “brutal dualism” which regarded mind and body as completely separate, and thus imagined the possibility of a “posthuman” self with no fleshly existence.

Worryingly, this ultra-capitalist creed was also embraced by some who termed themselves left-wing and who had swallowed the lie that technological and social progress amounted to the same thing.

The UK transhumanist Kevin Warwick wrote in I, Cyborg (2002) that his robotic future would leave behind those human beings who refused to abandon their real bodily existence and separate themselves from that hopelessly reactionary concept of nature: “If you are happy with your state as a human then so be it, you can remain as you are. But be warned – just as we humans split from our chimpanzee cousins years ago, so cyborgs will split from humans. Those who remain as humans are likely to become a sub-species. They will, effectively, be the chimpanzees of the future”. (18)

Garcia concluded his book by turning this label into a banner of defiance against the arrogant industrial-capitalist elite exemplified by Warwick.

He said that his work could be seen as fuel for an ideological movement opposing the life-hating transhumanist nightmare, an anti-capitalist, anti-industrialist “party of the chimpanzees of the future”. (19)

In an earlier work, Garcia praised the holistic and organic version of anarchism set out by Peter Kropotkin which “allows us, for instance, to see in every human society an organism which lives in a form most appropriately adapted to the environmental conditions, by means of increasingly active co-operation between its constituent parts”. (20)

Concluding a 2021 article on film director Terry Gilliam, in particular his classic film Brazil, Garcia wrote: “If we want to find a way out of the industrial labyrinth, let’s transform ourselves into free-swirling spirits”. (21)

Video link: Renaud Garcia – Le désert de la critique (3 mins)

1. network23.org/paulcudenec/25/12/26/deconstructing-our-resistance

2. Renaud Garcia, Le désert de la critique: Déconstruction et politique (Paris: L’Échappée, 2015).

3. Garcia, Le désert de la critique, p. 18.

4. Renaud Garcia, Le Sens des limites: contre l’abstraction capitaliste (Paris: L’Échappée, 2018).

5. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 288.

6. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 64.

7. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 36.

8. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 178.

9. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 111.

10. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 136.

11. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 169.

12. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, pp. 58-59.

13. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 90.

14. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 102.

15. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 205.

16. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, pp. 208-09.

17. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 210.

18. Kevin Warwick, I, Cyborg (London: Century, 2002), p. 4.

19. Garcia, Le Sens des limites, p. 287.

20. Renaud Garcia, La nature de l’entraide: Pierre Kropotkine et les fondements biologiques de l’anarchisme (Lyon: ENS Éditions, 2015), p. 63.

21. Renaud Garcia, ‘Terry Gilliam (vu de Brazil)‘.

5. Acorninfo

Questions are being asked by shrewd people across the UK about recent happenings which have been stoking up conflict on the streets. As one comment on a Substack post put it: “There have been several ‘events’ over the past two-three weeks (just after Labour entered office) – the attack on the solider in London, Leeds, Manchester Airport and this week Southport. All seem very well timed to nudge the public into accepting the components of a new ‘national capability’. It also all fits in very well with Agenda 2030 (restrictions on movement and more digital/tech surveillance). Just like the scamdemic, it looks like the public are being played again”.

* * *

In a fascinating video conversation with Mike Robinson and Vanessa Beeley of UK Column, academic David Miller reveals how Zionists have managed to control both “anti-fascism” and the “far right” in the UK (and notably Tommy Robinson, pictured). That particular section starts from around 40 mins.

* * *

Meanwhile, in a UK Column news broadcast, Ben Rubin has joined the dots between the new Labour government in the UK, the Fabian Society, Marxism and the Rothschilds. For more historical background on what lies behind the “left”, see ‘The false red flag‘ by Paul Cudenec.

* * *

In this good 15-minute video – with nearly three million views – investigative journalist Whitney Webb warns about the plan from BlackRock and the rest of the criminocracy to use a major crisis, such as war, to reset the economic system to their gain and everybody else’s loss. Whitney also recently took part in an excellent broad-ranging 80-minute interview with Neil Oliver.

* * *

“I am of the opinion that NATO was conceived from inception as the globalist World Army/Police Force. To complement the one-world financial system (e.g. IMF, World Bank, WTO), the world government (e.g. UN, EU, WEF), and so forth”. So says the ever-astute Hrvoje Morić of Geopolitics and Empire, who also recently conducted an in-depth interview with Winter Oak contributor Mees Baaijen.

* * *

Anti-globalist dissident Yuri Roshka – a journalist, editor, and politician in the Republic of Moldova who founded the Chisinau Forum – is about to be jailed for six years by the corrupt regime there. As he explains in an August 7 article, his prison sentence, on ridiculous trumped-up “corruption” charges, is clearly a political move by a state “controlled by the vast network of mercenaries of the international bankster George Soros”.

* * *

“For us as anarchists, all wars are capitalist wars and wars of capital. The only thing that wars produce are losers, death, misery and a pile of profit in the pockets of the capitalists… The conflict is not between right and left, but between ‘for the State’ and ‘against the State’ and as for anarchists it is very clear to us which side we are on”. The organisers of the Berlin-Kreuzberg Anarchist Bookfair explain why “anarchists” who want to fight for Ukraine are nothing of the sort.

* * *

Praising the “efficiency and functionality” of the Bank of Russia’s CBDC, Russian President Vladimir Putin has instructed his government to prepare for the widespread introduction of the digital ruble. “Now we need to take the next step, namely: move to a broader, full-scale implementation of the digital ruble in the economy, in business activities and in the financial sector”. This report from the Edward Slavsquat blog provides a useful reminder that a “multi-polar” world order will simply be the same world order in a new disguise.

* * *

“If we pause to think about this for a moment, the implications in a supposed democratic society are truly chilling. Individuals may well be prosecuted if they publish anything that someone else perceives to be ‘harmful’.” Iain Davis has published a very interesting series of articles on ‘The Bizarre Trial of Richard D. Hall’, the researcher who concluded that the Manchester Arena “bombing” was probably a psy-ops. Iain has also just brought out a book of his own on the question, entitled The Manchester Attack: An Independent Investigation.

* * *

“I am concerned about the privatising of the welfare system. I am concerned about creating a market of human vulnerability. I am concerned about the model where philanthropic foundations work hand in hand with the government, where they sit on investor roundtables and where the influence government policy and then they make money from people being harmed by the system”. In ‘Democracy 2.0 Capitalism 2.0‘, Kate Mason focuses on the threat to our lives, and our children’s lives, presented by the parasitical and totalitarian impact investment industry, aka impact slavery.

* * *

“What part does facial recognition and ANPR play in these CCTV policies and do Impact Investors have an interest in this data?” Ursula Edgington asks some important questions about the move towards smart cities and totalitarian surveillance in New Zealand – questions that need to be asked everywhere!

* * *

“The capture of public policymaking space by the private sector is set to accelerate due to a recent spate of memorandums of understanding between state institutions and influential private corporations involved in agriculture and agricultural services, including Bayer and Amazon”. A report from India – ‘Amazon Gets Fresh, Bayer Loves Basmati: Toxic Influences in Indian Agriculture‘.

* * *

“People want to live in safe communities and have lives with meaning and purpose. The way the modern world is going, it’s increasingly the case that people feel less safe and that their lives have no real meaning or purpose”. The latest overview of where we are today from our friends at Stirrings from Below.

* * *

“The individual cannot bargain with the State. The State recognises no coinage but power: and it issues the coins itself”. Ursula Le Guin