The End of Ireland's Great Consensus, by Keith Woods

Last Monday, May 6th, Irish people gathered in Dublin for a protest against the government’s immigration policy. This was the second Bank Holiday Monday in a row where an event like this happened, but this crowd was the biggest yet, reaching many thousands of people.

There is much that is very impressive about the anti-immigration movement in Ireland. This event was organised with little central leadership and promoted mostly by nationalist social media influencers. The crowd was diverse in age, with plenty of families and older people, a sight not typically seen at anti-immigration protests in Europe.

Another major strength of Ireland’s budding populism is the broad consensus on what Irish nationalism is. Because of Ireland’s unique history, our nationalists aren’t getting bogged down in sentimental attachments to dying empires and their civic conceptions of identity borrowed from imperial administrators. The idea that we would have to win a historical argument to make our case, or should identify with historical nationalist movements in other countries, is obviously ridiculous. Everyone in that crowd knows what an Irish person is, embraces Ireland’s revolutionary nationalist tradition, and is willing to affirm “Ireland belongs to the Irish”.

Of course, that doesn’t prevent infighting and party splits, and given the strength of this ‘Ur-Nationalism’ it is actually remarkable how many distinct factions and parties there exist within the populist scene, but that’s more a reflection of strategic disagreement (and a lot of egos involved) than fundamental ideological differences.

The rising populist movement in Ireland is all the more impressive considering that until recently Ireland had a very comfortable pro-immigration consensus. Regime journalists and politicians were proud that Ireland had no “far-right” movements. Irish liberals enjoyed tut-tutting at Brexit and Donald Trump and congratulating each other that we alone were showing the multicultural experiment could succeed if only everyone cast off their bigotries.

No more. The new way to signal status as a good steward of Official Ireland is to talk in solemn tones about “the increasing threat of the far right”, to nod thoughtfully at “extremism experts” who talk about how social media is fueling this threat, and to make allusions to “legitimate concerns” the far-right are exploiting, without ever really naming or addressing these legitimate concerns.

It’s becoming a great embarrassment for Ireland’s liberal establishment that a populist movement like this could arise, despite no institutional support, sympathetic media or significant financial support. It’s even more embarrassing for the left, who now cling to increasingly elaborate conspiracy theories about shadowy British forces pulling the strings of the far-right.

The alternative — that the working class is not interested in their message and has built their own “far-right”, because their top concern is replacement immigration — is unthinkable.

The Post-Troubles Consensus

Official Ireland could be forgiven for becoming complacent. The period from the Good Friday Agreement in 1997 to COVID and the Ukraine war was Official Ireland’s own unipolar moment: the great Post-Troubles Consensus.

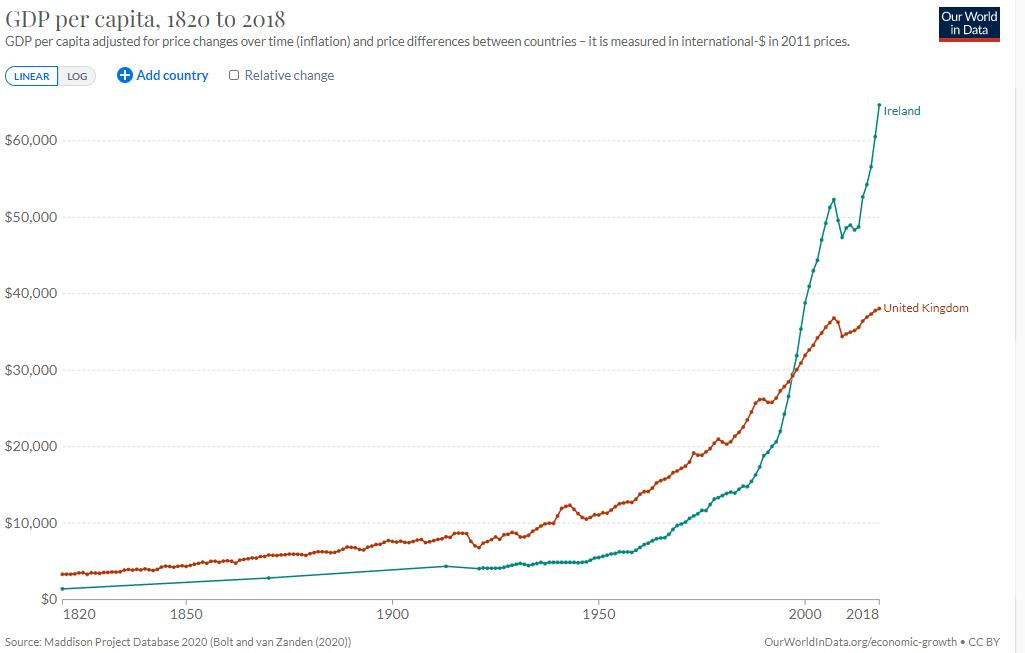

The sectarian conflict which had divided the island since partition was solved in a way satisfactory to all parties, with 94% of the Republic effectively voting for the agreement in a referendum. At the same time, Official Ireland’s liberal economic policies became a wild success, birthing the Celtic Tiger.

The Irish economy not only shed its status as a laggard in Europe, but with its spectacular growth rates became the envy of the world. Left/right divisions on economics were minimised by the vast wealth delivered by these policies — both generous tax breaks and massive increases in public spending were delivered, and those on the sidelines complaining about Ireland’s failure to more consistently follow a socialist or free market path seemed like cranks.

Ireland had a long consensus across elected parties, who all agreed on the path of economic liberalisation which Ireland had followed since the 1970s. Ireland’s future would be as a high tech, skilled economy closely integrated into the European Union. Even the Labour party and the fringe Trotskyist groupings in Dáil Éireann treated the 12.5% corporation tax — central to attracting multinational corporations to Ireland — as sacrosanct. Central also to this consensus was Ireland’s rapid embrace of social liberalism, and a shared narrative about the “old Ireland” — anything before the 1990s — where the Irish suffered under an oppressive Catholic orthodoxy.

The 2000s and 2010s were ripe with public self-flagellation rituals where we interrogated our past, and the worst abuses of the old regime — Magdalene Laundries, child sexual abuse in the church, the IRA, the climate of political corruption within the historically dominant Fianna Fáil party — were regular topics of exploration. This accelerated after a disastrous economic crash in 2008, where the Celtic Tiger optimism made way for widespread anger and cynicism about the whole establishment.

There was somewhat of a populist response in the 2011 election, but this was mostly non-ideological, as is typical of Irish politics. While the ruling Fianna Fáil party suffered it’s worst defeat ever, the major beneficiaries were parties which had supported the same economic excesses of the Celtic Tiger period themselves, as well as a large contingent of non-ideological or leftist independent candidates. Insofar as there was a populist opposition in this period, it was along the lines of early 2010s leftist economic populism, a similar energy and style to Occupy Wall Street, Greece’s Syriza or Spain’s Podemos. But the hard left was never taken seriously enough as a real alternative to be anything but a few loud voices of opposition.

When the economic ship was steadied after years of painful austerity, it seemed like a return to the predictable consensus politics of old. After the 2020 election, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael entered a coalition government for the first time in history. This was hugely significant, as their split in the origins of the Civil War had defined politics for a century in the Republic. If there had been historic ideological distinction between the parties, it had totally dissolved by 2020.

There was a time when Fianna Fáil had been “the Republican party”, and more closely associated with Irish nationalism, protectionism and economic populism, while Fine Gael was seen as more of a traditional center-right liberal party. Under the great consensus, these distinctions became meaningless. After Good Friday, we put behind us the Northern question and any grandstanding about who the real inheritors of the nationalist tradition were. After the success of EU integration and economic liberalism, protectionism and developmental nationalism were left behind.

The ideological uniparty had now coalesced (alongside the Green Party) into one great governing uniparty. The dominant opposition faction to emerge from this period was Sinn Féin, who, while fully embracing the liberal consensus, challenged the government with a more economically populist agenda. Sinn Féin became the largest party in the country. Their rise in popularity seemed inexorable, and the party seemed on course to lead a government, until the emergence of anti-immigration populism in recent years.

How could this happen? How could a country with the greatest popular support for EU membership, no popular right-wing party, and a strong elite and media consensus be ground for the growth of a popular anti-immigration movement?

In a sense, the success of the Irish liberal regime has been its undoing.

I have previously cited the book How Democracies Die, where political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt identified a strong center-right party as crucial to the maintenance of democracy. Of course, Levitsky and Ziblatt share the liberal idea of democracy as institutionalised pluralism and “democratic values”, so what they are really analysing is how to stifle the rise of populism, hence their identification of Trump and Orban as threats to democracy. They argue that the main reason for the rise of Hitler was the lack of a cohesive force on the center-right in the 1930s:

Before the 1940s, Germany never had a conservative party that was both well-organized and electorally successful, on the one hand, and moderate and democratic on the other. German conservatism was perennially wracked by internal division and organizational weakness. In particular, the highly charged divide between conservative Protestants and Catholics created a political vacuum on the center-right that extremist and authoritarian forces could exploit. This dynamic reached its nadir in Hitler’s march to power.

Remedying this defect, conservative parties like the German CDU became a pillar of Europe’s postwar democracies. Ireland’s case is quite unique here. While most European democracies have a major center-right and center-left party which trade power back and forth, Ireland’s bipartisan split has been along historical tribal lines rather than any ideological distinction. Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil represented the two sides of Ireland’s tragic civil war, and the tribal attachment to one side or the other lasted well beyond the conflict itself. There is also a good deal of personality politics involved, as Irish people tend to vote for parliamentary candidates on the basis of what they can “get done” for their constituency while in office.

But since Ireland was a very socially conservative country and there was no major leftist political force, both parties filled the kind of role that traditional center-right conservative parties did in the rest of Europe. However, since the 2000s, in the midst of the great consensus, the parties abandoned all traces of social conservatism and nationalism to become run of the mill liberal parties.

Every party supported the gay marriage referendum in 2015, which passed with 62% of the vote, and none opposed the 2018 amendment to the constitution to introduce abortion to Ireland, which only 33% rejected. But this left about a third of the Irish population who still believed in traditional marriage and were strongly pro-life with no representation.

Probably, a similar or higher number were also opposed to the government’s mass-immigration policies, but Official Ireland didn’t see this as much of a problem. The media was grown up enough to collude to protect “democratic values”, to freeze these bad opinions out. Politicians too, were responsible enough to not play with the dangerous forces of populism. With billions per year directed to Ireland’s bloated NGO complex, the last holdouts of Ireland’s backward past would eventually die or be socially engineered into conformity.

The lack of representation for the disenchanted in the new Ireland stacked up a mound of dry wood, but Official Ireland were confident they could deny it oxygen. Post-COVID, there was a convergence of factors whose sparks lit the fire that now threatens to explode the great Irish consensus.

Explosion

The Irish government pursued a particularly draconian path on COVID. In the summer of 2021, an Oxford University report labelled Ireland’s lockdown the strictest in the EU, and “one of the harshest coronavirus lockdowns in the world”. Still, no political party or popular publication dared to dissent on the wisdom of this path, which included limiting people to a 5km travel radius strictly enforced by Garda checkpoints.

As it did everywhere in the West, COVID contributed to a kind of populist (or at least anti-government) sentiment, but this was disorganised, undirected, and often prone to falling into wrong-headed and discrediting conspiracy theories. When the lockdowns ended and the country again opened its doors, events directed this back to immigration.

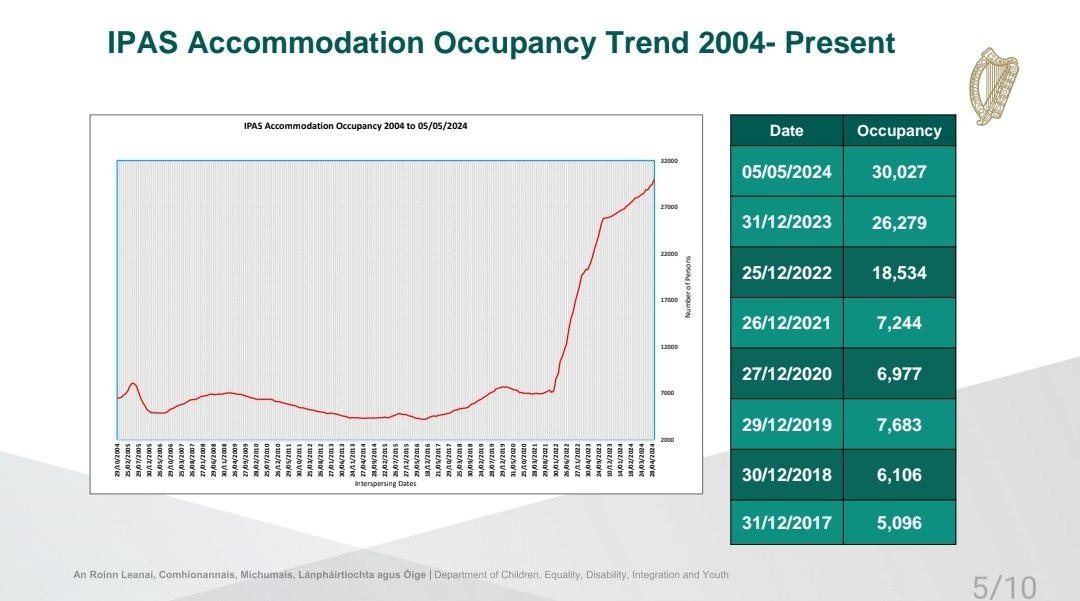

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was the black swan event that produced a refugee crisis and began to overwhelm the government’s management of the migration system. By December 2022, Ireland had accepted more than 67 thousand Ukrainian refugees. In 2023, the rate of Ukrainians who arrived in Ireland was a staggering 10 times the EU average, with half listing state provided accommodation as their reason for choosing Ireland.

At the same time, the influx of asylum seekers from outside Europe began to dramatically increase, with the government’s lax policy on deportations and generous benefits for asylum seekers making it an attractive target for human traffickers and illegal immigrants alike.

2022 was also the year of the tragic murder of Ashling Murphy, a primary school teacher butchered in broad daylight by a Roma Gypsy immigrant from Slovakia who had lived on welfare. Just three months later, the badly mutilated corpses of two gay men were found in their own homes in Sligo, with one decapitated. The perpetrator this time was a 23 year old Iraqi immigrant.

Due to the victims and the particularly brutal nature of these killings, they were highly publicised and discussed. The media tried to turn the blame for these murders onto Ireland’s culture of misogyny or homophobia, but by now much of the public was becoming frustrated with media silence on the immigration issue.

In November of that year, the budding populist sentiment found a focal point with the beginning of a large people’s movement in the working class community of East Wall in inner city Dublin, where former offices in the community were transformed into military style accommodation for hundreds of male migrants. East Wall residents held a number of successful protests, including a blockade of the Dublin Port Tunnel.

This not only forced the question of immigration to the front of political discussion, but also encouraged the spread of similar protest movements in other areas of the country hosting migrant centers. A year later, when an Algerian migrant stabbed three young children and a carer outside a school in Dublin, the discontent that was years building spilled onto the streets in a night of protest and rioting. This was also the point at which Conor McGregor began to express support and loudly condemn the Irish government over immigration policy.

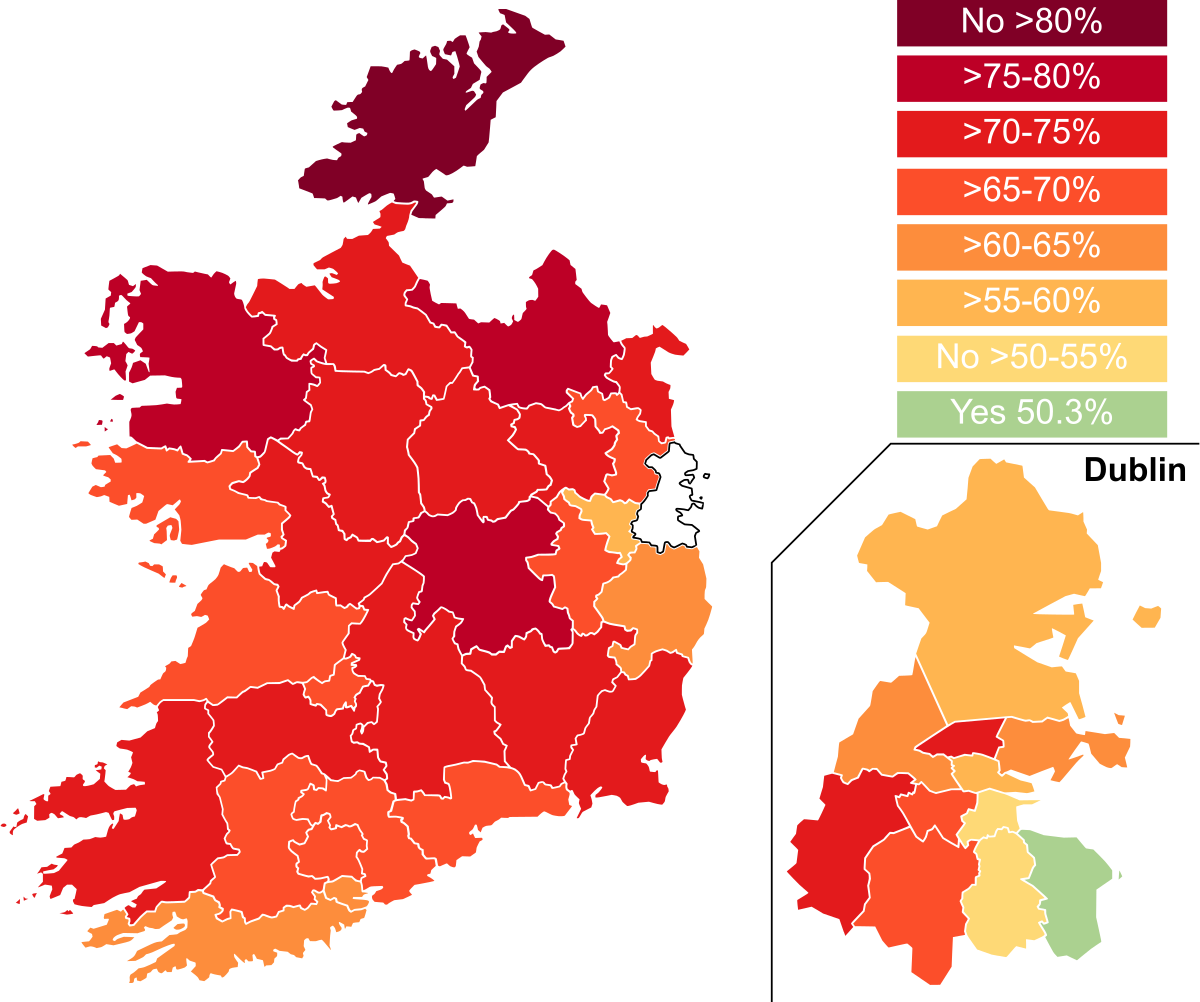

The rising populist spirit seemingly found electoral expression at last with the rejection of a government referendum in March. The government proposed amending the constitution, removing supposedly outdated language about the state’s obligation to “endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home” with gender neutral language about “durable relationships”.

Although every major party supported this change, it came to be seen variously as “woke”, part of the government’s liberal agenda, a pointless distraction from more pressing issues, and, potentially, a change that would facilitate “chain migration” to Ireland. Whatever the reasons for opposing the amendment, they were all populist in nature. And though the amendment was heavily favoured to be carried by a population that had voted a resounding “yes” to the gay marriage and abortion referendums, this referendum was soundly defeated. Over 67% of the electorate voted no, with only the highly affluent, liberal constituency of Dún Laoghaire supporting one of the two proposed amendments.

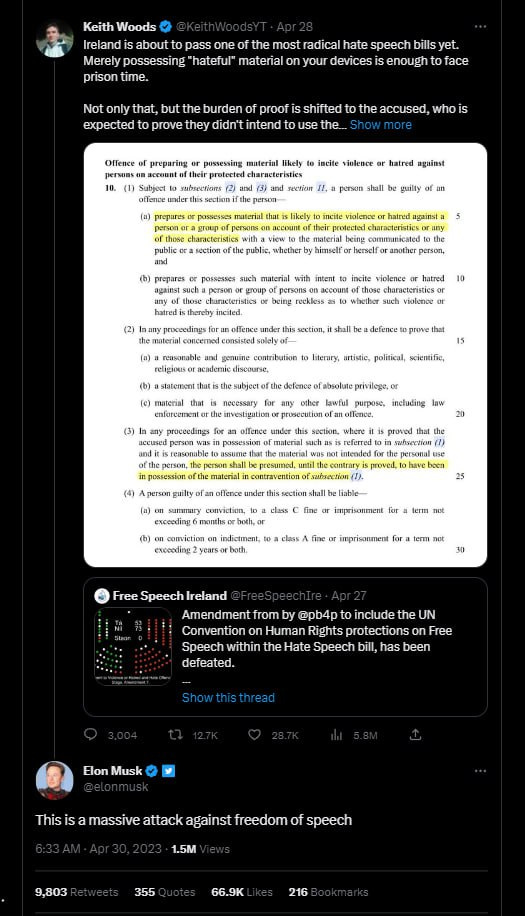

Apparently fearing the worst from this result, some government TD’s have begun to backtrack on “the woke agenda”, and many have now abandoned and begun to express criticism of Ireland’s controversial Hate Speech law, which was rolling through the legislative process unopposed until it was thrust it into public debate last year — sparked partly by international attention coming from Elon Musk’s response to my highlighting the most controversial aspects of the bill, and also by an energetic people’s campaign against it — and revealed it to be deeply unpopular.

To our elites’ shame, Ireland was late in embracing liberalism. And they compensated by making a show of embracing it with as much pace and enthusiasm as they could display. But they made a mistake in not boiling the frog slowly. Had they just gotten on top of illegal immigration and managed numbers, the backlash to mass-legal immigration would probably have remained manageable. Not only have they failed to tackle the explosion in illegal immigrants, but in the most recent year on record they increased the population by 3% through legal immigration, importing another 141,600 people.

Now, as Ireland heads for local and European elections this June, the immigration issue dominates politics. According to a recent poll, 41% of Irish people now consider immigration the top political issue, a rise of 15% in just one month. 54% rank housing as their top area of concern, a problem obviously heavily impacted by mass-immigration. Over a third of Irish people say they would consider voting for an explicitly anti-immigration party. Political candidates are reporting widespread concern at the doors of voters over immigration. It seems that, at last, there is now space for a national populist breakthrough in Irish politics.

Will this happen? These elections are a big unknown. In the past, the Irish electorate has flattered to deceive, with a sense of growing populism and unrest failing to translate to electoral breakthrough. The reasons for this are manifold. Politics is still a very middle class business here: working class areas of Dublin seem the most ripe for anti-immigration candidates, but they also have some of the lowest rates of voter registration. The most liberal, affluent areas have the highest rates of registration, because those are the people engaged with electoral politics.

There is also a good deal of tribalism and personality politics still common in Ireland which makes voters more reluctant to lend their vote to new parties and outsider candidates. I recently canvassed farmers and rural voters in Athenry, Co. Galway. Had they been polled issue by issue, I’m confident they would have come up with a platform much like the National Party’s, and they all saw immigration as a pressing issue. Widespread agreement, yet when it came to how they would vote, many were committed to an independent candidate who they were unaware had a terrible stance on immigration, but who they saw as a trustworthy representative for various other reasons.

Even more frustrating is the fact that in polls on immigration, Sinn Féin supporters consistently show some of the highest rates of opposition to mass-immigration, apparently disconnected from their leftist, open borders leadership. It may be that only many more years of betrayal on this issue will force voters to get behind radical change, but these elections should still provide a modest electoral breakthrough which will go a long way to legitimising anti-immigration populism as a serious force in Ireland with a real mandate.

Regardless of the fate of any party, and there are many that have now emerged to try and seize the opportunity to represent the nationalist vote, populist forces in Ireland have become extremely anti-fragile the last few years: the use of Telegram and WhatsApp groups to disseminate information quickly and organise protests; the dominance of Irish political Twitter by nationalist influencers, evident in the persistent dominance of hashtags like #IrelandisFull and their ability to organise large protests like the one witnessed recently; the rise of “citizen journalists” like Philip Dwyer giving people a direct feed of the problems caused by the immigration crisis; the emergence of independent online media like Gript and the Burkean which have filled a gap left by the mainstream media; and the hard alignment of Dublin’s “youngfellas” — working class inner city young men behind much of the civil disobedience — with the nationalist movement.

All these factors have helped make Ireland’s anti-immigration movement one of the most effective in Europe, even without elected representatives. And here, there is no phony liberal center-right party to gobble up nationalist votes with diversionary rhetoric focused solely on illegal immigration or other side issues. If the strength of Ireland’s liberal establishment for years was its consensus based politics and lack of a right-populist force, that cohesion has backfired.

Those on the outside have been forced to adapt and build their own force from the ground up. It is a force that can no longer be ignored or handwaved away as the fringes of the “far-right”, and as the government shows no signs of yielding on its accelerationist policies of replacement migration, it is a force destined to emerge as the only remaining challenge to the vision of Official Ireland, which would be the final death of the Irish nation.

Note

Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How democracies die. Crown, 2019.