Democracy: Its Uses and Annoying Bits

I enjoyed Fred Reed’s April 24 essay “Ignorance, Its Uses and Nurture,” which refers to universal suffrage in anything larger than a small town as a “crackpot” idea. In a mere thousand words, Reed painted the American public as entirely incapable and unqualified to understand United States foreign policy, let alone vote on it. Therefore, he concludes, the entire democratic system is a sham. Yes, the statistics he presents bolster his point admirably. But maybe not as much as epic burns such as this one:

If we ignore exceptions and degrees, the public can be regarded as a vast, semi-comatose polyp that knows only whether it is comfortable or cold and wet and has enough to eat. If the economy is good, people will vote for incumbents, whether these have any responsibility for the prosperity or not. If wars can be fought without inconveniencing them, in places not actually within their visual horizon, they will pay scant attention. They will not concern themselves with education as long as their children get good grades, however unrelated to anything learned. Their interests are local, though they can be stirred up over this football team or that, this Trump or that Biden, or morality plays about police brutality or the righteous heroism of Ukrainians.

Yeesh. Who would want to be ruled by a bunch of rubes like that?

While Reed does an excellent job promoting democracy’s drawbacks, he’s effectively painting only one half of the picture. Anyone wishing to highlight the uselessness and stupidity of universal suffrage must first get past the classic defense of democracy, which owns up to its drawbacks yet proclaims it superior to all other options — namely fascism, Communism, or any other system in which there is top-down authority that cannot be changed. Now, I am not going to defend this defense, since I too oppose universal suffrage. But it’s simply not enough to bash the voting public as lizard-brain peons, unless one can also show how putting decisive power in the hands of another group of people is the better way to go.

Then there’s the second, more substantive, defense of democracy – that authoritarian systems have drawbacks, too. They tend to work quite well — until they don’t. One of the first things we learn in political science classes is that the very best form of government is a monarchy run by a good king. And that’s great. Everybody loves a good king. But what happens when you get a bad king? Then all sorts of misery can follow, and history is rife with examples of that. Further, it is often impossible to know who is going to be a bad king until it is too late. And since, according to Graham Chapman, “Ya don’t vote for kings,” what do you do then? Convince your wealthy friends to bribe some charismatic military leaders into forming a junta and storming the palace, while you write up your lengthy assassination plans and hope not to get the oval end of a rope?

According to Robert Graves in his assiduously-researched historical novel I, Claudius, Rome went from having a more-or-less good and honorable king (Augustus) to a competent and corrupt king (Tiberius) to a delusional and sadistic king (Caligula) all within 25 years. And do you know why Tiberius selected the obviously insane Caligula to succeed him? Because he was concerned that his tepid popularity with the Roman public would taint his legacy, and so wanted to be followed by someone so fiendishly awful that he, Tiberius, could only look good in comparison. Of course, whatever damage this Caligula kid would end up doing to the Roman people after Tiberius’ inevitable demise was of little concern.

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s Western Civilization Bites Back here.

Of all the petty, pig-headed, egotistical, and sand-poundingly stupid reasons for nearly destroying an empire, this has to take the cake. And you cannot pin that one on democracy.

In another assiduously-researched study, David Hoggan’s The Forced War (recently reviewed at Counter-Currents and The Occidental Observer gives us National Socialist Germany’s perspective on the lead-up to the Second World War. In my view, Hoggan convincingly argues that Adolf Hitler made reasonable demands throughout the 1930s for the sake of the Germanic people, which had been left scattered and disorganized across the European continent by the Treaty of Versailles. The war started not with Germany’s (and the Soviet Union’s) invasion of a clearly intractable and belligerent Poland, but with a warmongering England and America that used every underhanded tactic they could to goad Germany into starting a war.

Whether he realized it or not, Hoggan uncovered the Achilles’ heel of all authoritative (read: non-democratic) governments: They are relatively easy to goad into war. Look at it like this: Democracy, in theory, will put people from all corners of the political spectrum into one room, where they can bicker all day about how best to waste taxpayer money. I know it may not be quite like that in reality, but any semi-functional democracy will end up with at least some people in government who not only possess opposing ideologies, but actual power as well.

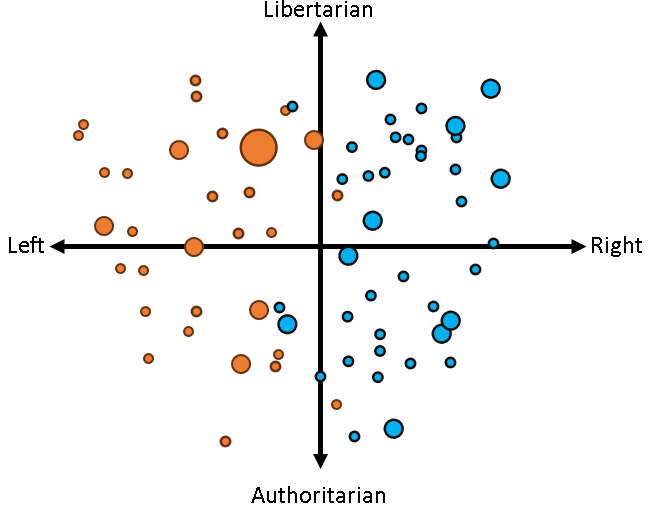

I suppose a totally unscientific, armchair theoretician’s scatterplot of such a theoretical democratic government might look like this, with the colors representing political parties and sizes representing a certain individual’s power or influence:

As you can see, the elites in this theoretical democratic country have drastically different perspectives and agendas. In order for the elites of another country to goad this one into war without actually attacking it, they would have to alienate quite a few people in quite a few different ways. This is not particularly easy to do, as the British discovered in the late 1930s. President Franklin Roosevelt really did want to declare war on Germany, but was hamstrung because he was merely the President of a democracy. He faced too much ideological opposition in government to get away with such a bold move.

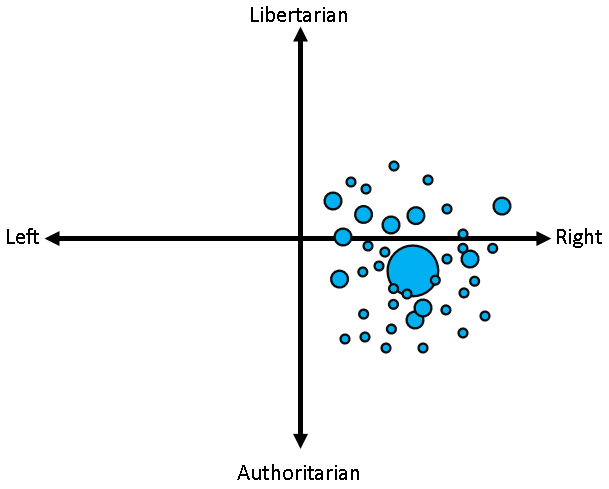

On the other hand, an equally unscientific armchair analysis of Nazi Germany’s government might look something like this (and take a wild guess at who the big circle in the middle represents):

Because the leaders of Nazi Germany were so concentrated in one section of the 2D ideological continuum and shared so many of the same concerns and sensibilities, it was relatively easy for its enemies to goad them into war. Make a few angry threats over Danzig, harass the German minority in Poland, fabricate a hoax or two, spread propagandistic lies about the German leaders, call them “Huns” in a radio broadcast, and soon enough you’ll have a majority of the German leadership that matters ready and willing to launch an invasion. Yes, it wasn’t quite as simple as that, but could the goading tactics used against Germany have worked against Roosevelt or Neville Chamberlain? Probably not — not because those men wanted peace at all costs, but because they were leading fractious democratic governments that had been given to them by the people, which, due to constant ideological squabbling, are not suited for quick, bold action without a quick, bold form of instigation — such as a Pearl Harbor (or for that matter, a Fort Sumter, a Maine, a Gulf of Tonkin, or a 9/11).

I’m reminded of the “Romantics and Utilitarians” chapter in Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind, which praises the slowness of conservative government. Governments that are strapped by checks and balances and must go through a tremendous rigmarole to get things accomplished can be frustrating. At the same time, however, such a government will be less tempted by tyranny.

In the view of men like [Edmund] Burke and [Sir Walter] Scott, the slowness and clumsiness of old-fashioned law must be tolerated (at least until gradual adjustment may be arranged) for the sake of the safeguards to liberty and property that wither away in any legal system which accords pride of place to speed and neatness.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here.

Democracy as we know it today is rather like that. Having the shrewd brainwash the dumb into electing the corrupt, and then giving the corrupt and their shrewd handlers trillions in Monopoly money, is certainly an invitation for all sorts of domestic acrimony and shady shenanigans. But such a government will not be easily goaded into war, because in such a clown show there is a good chance that some of the bickerers might sympathize with the people doing the goading.

That’s basically my point, and I could be right or wrong about this. But I think that any condemnation of democracy should at least pay lip service to the fact that it was democracy’s opposite that may have contributed most to the onset of Western civilization’s greatest catastrophe.

In closing, I would like to point out a few things that this essay is not:

- As with any political theory, I’m sure there are historical examples which either do not support or outright refute it (Iraq War, I’m looking at you). My point is that relatively speaking, it may be easier to goad a more authoritarian and centralized government into launching full-scale invasions of other countries than a more democratic, decentralized one. It can be argued that without 9/11 there would not have been an Iraq War, while the reasons for Hitler’s invasion of Poland were much less dramatic and easier to pull off.

- A condemnation of Nazi Germany or fascism. Despite their virtues, any system of government will have its natural drawbacks. It could very well be that having big, prominent buttons which say “Don’t push me!” is one of those for both of these systems.

- A criticism of Hitler’s decision to invade Poland. At least according to Hoggan, the Poles, as a result of their hostile and deceitful behavior in the late 1930s, were practically asking to be invaded by the Germans. The point is that it was basically Hitler’s decision, and he could have reversed it if he had wanted. On the other hand, it took a Pearl Harbor and over a thousand dead American servicemen to convince not just Roosevelt, but a majority of his political and ideological opponents in the American government to go to war. That’s a big difference.

- An argument in favor of universal suffrage. Reed does an excellent job of blasting this idea. I do see the upside in the constant bickering among lawmakers in a functioning democracy, however. The fact that we have so many special interests wrangling dishonestly over whatever wasteful and self-serving projects they can foist upon their opponent’s constituents before their representatives get voted out may be a bad thing, but it may also be a good safeguard against a powerful dictator waking up one morning and feeling war in his loins.

- A theory without a proposed solution. Maybe there is a way we can distill the best aspects of democracy while eschewing the worst. Perhaps forming a meritocratic aristocracy among the populace to determine who gets to vote and who doesn’t might be an improvement on what we’ve encountered in the past century. In this way, the squabbling in government won’t change, but the quality of the people doing the squabbling will — all while preserving the natural safeguards against going to war. This may be a topic for a future essay.