Ross Perot and the US Presidential Election of 1992

words

The Chernobyl nuclear reactor in the Soviet Union suffered a catastrophic meltdown in April 1986. The disaster was too big to ignore, and it shattered the prestige upon which the Evil Empire was built. Thereafter the entirety of the Communist bloc in Europe started to collapse. In November 1989 the Berlin Wall came down, and then anti-Communist revolutions swept across Eastern Europe. “The world,” according to a 1991 hit song, “woke up from history.” The Soviet Union was officially dissolved on Christmas Day in 1991. The end of the Cold War brought a moment of euphoria to the Zionist-aligned political elite in the United States, and many globalist intellectuals thought that “liberal democracy” had reached a global permanence.

The end of the Cold War and the uncertainties that resulted from it underpinned the United States presidential election of 1992. At the time, however, the election only seemed notable in that an independent candidate, Ross Perot, made an unusually strong third-party run. Perot and the other candidates that represented the “fringe” in 1992 are worth reexamining.

The establishment incumbent

At the United States’ helm at the end of the Cold War was President George Herbert Walker Bush. President Bush began his career as a pilot in the United States Navy during the Second World War. The character of his service during the war was beyond valorous. Bush was a Yankee who later moved to Texas, where he got into in the oil business and became wealthy. He entered politics in the early 1960s, just as the Republicans were beginning to capture voters in the traditionally Democrat-dominated South. Bush successfully maneuvered his career through the social revolutions of the 1960s and was nominated as Ronald Reagan’s Vice President in the 1980 election. Eight years later, he was elected President in his own right.

Bush was the right man for the job on the international scene. He successfully navigated the US through the collapse of the Communist bloc and then assembled and led a diverse coalition to remove the Iraqi army from Kuwait in 1991. At the end of the Persian Gulf War, Bush’s approval rating reached 90%. He seemed unbeatable heading into the 1992 election.

Communism in Romania collapsed in December of 1989. Romania had been one of the last loyal Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe.

Events beyond Bush’s control cut into his reelection chances, however. The first wound to his presidency came just before he was first elected in 1988, when the savings and loan industry collapsed and the US government had to step in with an expensive bailout. One of President Bush’s sons was working in the industry, so the appearance of impropriety remained a sore point for many Americans. The entire economy fell into a recession in the summer of 1990. It was short and mild, but only became clear in retrospect. In the spring of 1992, sub-Saharans rioted in response to the acquittal of four Los Angeles policemen who’d been filmed beating a sub-Saharan suspect named Rodney King. Meanwhile, deindustrialization was cutting deeply into the prosperity of those in the Rust Belt. Besides all this, George H. W. Bush was an establishment Republican and a supporter of “civil rights.” He signed the Civil Rights Act of 1991 into law in order to further shore up the illicit second constitution that is the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Bush also raised taxes after promising not to, a move that enraged many Republicans.

Bush’s vulnerability first manifested within the Republican Party itself. Pat Buchanan, a leading member of the conservative movement, launched his own candidacy in early 1992. Another challenger was David Duke, a Louisiana politician and principled white advocate who would go on to write an excellent book on the Jewish Question. Incumbent presidents who face significant primary challengers are in deep political trouble.

The Democratic challengers

As for the Democrats, a series of moderate liberals put their hats in the ring. They were mostly old-stock Americans or assimilated white ethnics. The Democratic challengers had sympathies which overlapped with those of conservative voters who might otherwise vote Republican. The 1990s was a time when one could politically be a “social liberal” while also being a “fiscal conservative” as well as “tough on crime.” The Democrats eventually nominated a moderate named Bill Clinton.

If one rewatches the 1992 presidential debates from a non-partisan perspective, Bill Clinton and Al Gore clearly dominated. Additionally, Clinton could genuinely empathize with others. George H. W. Bush was unable to formulate a winning message and came across as having low energy. Ultimately, both the Republicans and Democrats offered neo-liberal economic policies. Bush and Quayle wanted to shove the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) down America’s deindustrializing throat, and Clinton and Gore wanted to ensure that Mexico followed environmental laws before they strip-mined America of its jobs through NAFTA and other neo-liberal free trade agreements.

The independent challenger

The outsider who shook things up in 1992 was Henry Ross Perot, a native Texan who rose from a humble background to become a successful businessman in the computer industry. He declared himself as an independent candidate for the presidency in February 1992. His quixotic run took votes away from Bush and most certainly left the winner, Bill Clinton, without a popular mandate, allowing for a slow burn of discontent through the first two years of Clinton’s presidency.

Perot was not a white advocate, but he was well outside the political mainstream regardless. The social problems which led to his presidential run had their roots in the “civil rights” disaster, although this wasn’t so clear in 1992. Perot was a prophet in that he predicted the problems that would ensue from neo-liberal trade deals such as NAFTA, and he likewise had opposed the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Although his views were largely ignored at the time, in retrospect we can see that the war created more problems than it solved. Perot also sought to tackle a terrible problem of the time: the plight of those Americans who had been taken as prisoners of war and who were still being held hostage abroad.

The man from Texarkana

Ross Perot was born in Texarkana, Texas on June 27, 1930 to a strict Christian family. Instead of revolting against his parents’ piety, he embraced it. He worked hard at every task he was given. Perot was accepted at the US Naval Academy in 1949 and commissioned as an Ensign in 1953. His first assignment was on a destroyer bound for Korea, where the war was still being waged. Word reached the ship that the war had ended when the destroyer reached Midway Island. Perot thus had the fortune — or misfortune, depending on one’s point of view — of just missing the chance to see combat.

Perot thrived in the Navy for a time, but once the Korean War ended he became bored, finding his fellow sailors to be undisciplined. He spent much of his stint in the Navy as a junior officer who was responsible for bailing drunken sailors out of local prisons and handing out penicillin to treat venereal diseases. Perot applied for an early discharge, but before he left the service he was assigned to manage an early form of the computer; the experience allowed him to land a job at IBM following his release from service in 1957.

Perot worked as a salesman for IBM, and soon realized three things about the company’s clients: they needed technical support, computers were often left idle, and that data was the thing they wanted most. With a $1,000 investment from his wife, Margot Birmingham Perot, he started Electronic Data Systems (EDS) in 1962.

EDS rented time on computers which would have otherwise been idle to process payroll for various clients, manage insurance claims, and analyze other forms of data. Perot had tapped into a new industry that was soon to become extremely important. His real talent was for hiring good people, however. He preferred married white men, and his employees wore coats and ties to work and kept their hair short. By the end of the 1960s, Perot started to focus on hiring Vietnam veterans who were in their early twenties but who had attained a great deal of maturity from their time in the service. This was at a time when many Vietnam vets found it difficult to find employment after reentering civilian life.

EDS began to make real money when President Lyndon Baines Johnson enacted Medicare and Medicaid as part of his broader Great Society reforms. EDS carried out the data processing for those programs in Texas, and the company’s profits jumped massively starting in 1965. EDS then expanded across the country to help all the states with these programs. Perot was on his way to becoming the first tech billionaire.

Although Perot was a “self-made man,” the way in which he acquired his fortune needs to be critically analyzed. His main client in the 1960s was a federal welfare program that had been enacted by a President who was among the last of the genuine believers in Keynesianism and “New Deal” economic systems. Perot was a capitalist, but he was one whose prosperity depended upon a socialist program.

Data processing is a vital function, but EDS ultimately became a catchment area to receive federal funds. Perot was in an industry in which money came from taxing other parts of the American economy — and those parts, such as manufacturing, were collapsing. Missing tax revenues were made up by borrowing money.

Managing Medicare and Medicaid accounts were Perot’s cash cows. To keep his grip on his government clients, Perot hired lobbyists, a platoon of good lawyers, and played for keeps. When he lost a lucrative government contract, for example, he fought hard by claiming that the contracting process had been unfair, and thus won the contract back. Eventually EDS merged with General Motors. Perot predictably clashed with the auto executives and was bought out for $750 million. EDS saved General Motors $200 million per year.

To bring out the prisoners and them that sit in darkness

On August 5, 1964, Lieutenant J. G. Everett Alvarez, Jr. of the US Navy was shot down over North Vietnam while piloting an A-4 Skyhawk. He was the first of hundreds of American prisoners of war during the Vietnam conflict. Once the Nixon administration began the US withdrawal from Vietnam, the prisoner of war issue became embedded in the collective American consciousness. Ross Perot became prominent advocate for the POWs and their families.

Perot attempted to fly aid packages to the prisoners in North Vietnam in 1968. The North Vietnamese wouldn’t allow Perot’s plane to land, however, so he stopped in Laos. The North Vietnamese were willing to accept the aid packages provided that they were smaller in size, so Perot flew them to Alaska and organized a repacking team made up of ordinary citizens. Then, Perot attempted to get the supplies to the POWs via the Soviet Union. He eventually flew the supplies from Alaska to Europe by flying over the Arctic Sea before finally realizing that the Communists were never going to cooperate. The mission was a failure, but Perot’s quixotic attempt to get supplies to the prisoners was a major story in the American media and made him a household name. When the POWs were finally released, Perot hosted them at an event in San Francisco.

EDS expanded its operations into the Middle East during the 1970s, and also began handling Iran’s social security program. The Shah’s regime was on the verge of collapse, however. Just before the Iranian Revolution, two EDS employees, Bill Gaylord and Paul Chiapparone, were arrested by the Shah’s underlings and imprisoned. Americans began leaving Iran as the situation deteriorated.

Perot was determined to free his employees. He hired retired US Army Colonel “Bull” Simons to lead and train a team of EDS employees who were veterans to rescue the prisoners. Simons had led a raid on a POW camp in Vietnam and was an experienced soldier. Simon’s “commando team” consisted of married men in their late 30s. The effort had all the makings of a fiasco. Perot’s legal team advised him against making a private effort to retrieve the jailed men and instead recommended that he go through official channels. Perot was insistent, however. He even went to Tehran himself and spoke with his imprisoned employees at great risk.

Col. Simons and the team infiltrated into Iran and carefully considered every potential course of action. Simons realized that the Iranian Revolution was progressing similarly to how the French one had, and that a mob of pro-Ayatollah supporters could storm the prison and release the inmates at the jail, many of whom were political prisoners, as happened at the Bastille in Paris in July 1789. Simons and an Iranian EDS employee organized such a mob, and every prisoner was freed along with the two Americans. The group then fled overland and across the mountains to Turkey, and from there to the United States.

Ken Follett wrote a book based on the affair that was turned into miniseries on NBC in 1986. It is an engaging fictionalized account of the event, and it hits all the right notes: a loyal employer carrying out noblesse oblige, chaste wives fighting for their captured husbands, and valorous Americans who refuse to leave any man behind. There was an all-star cast as well: Burt Lancaster played Simons, and Perot was played by Richard Crenna.

Perot remained involved in the POW/MIA issue, which continued to linger after the Vietnam War ended. There were widespread rumors that some Americans were still being secretly held by the Vietnamese. Ultimately, no prisoners were ever found, although it is nevertheless the case that more than a thousand Americans had gone missing across Southeast Asia at the time. The POW/MIA issue became a cultural force in the 1970s and persisted for decades afterwards. There were several popular movies made about Americans captured or stranded in Vietnam such as The Deer Hunter, the Missing in Action series, Rambo: First Blood Part II, and Bat*21. The issue was bolstered by the Iranian Hostage Crisis in 1979-81 as well as the Lebanese hostage crisis which plagued the Reagan administration during the 1980s. Perot donated money to Oliver North in an attempt to free the Americans in Lebanon.

Perot poured a great deal of money into POW/MIA causes, funding expeditions and investigations. One such investigator was a colorful retired Special Forces operator named Bo Gritz, who would also run for President via the small Populist Party in 1992. (David Duke had been the party’s nominee in 1988.) The Populist Party had been founded by Willis Carto. Gritz didn’t focus his campaign on racial issues, however, instead speaking about the national debt, the Federal Reserve, and America’s loss of American sovereignty in George H. W. Bush’s “New World Order,” which he believed was leading to a “one-world government” that would enslave Americans.

It is possible that Perot’s money helped to keep the POW/MIA issue in the public’s mind long after the end of the Vietnam War. Retired soldiers seeking fame were certainly incentivized to keep the rumors of shackled American patriots forced into slave labor in Asian salt mines going. Perot was also initially involved in the building of the controversial Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. He pulled out, however, once the memorial’s design was revealed, feeling it was too negative. Some felt that he had come out of the affair appearing petty.

1992 presidential run

Perot had been involved in politics since the late 1960s. Aside from his POW/MIA activist and a brief foray into the War on Drugs, much of his activism was self-interested, consisting of lobbying efforts to further his business interests. By the late 1980s, crime had been spiraling out of control across the US for more than two decades. After three policemen were killed in Dallas in 1988, Perot got involved in police reform. He held listening sessions with police in order to get a grip on the issues, and the officers told him that the Citizens’ Review Board was holding them back, a Dallas government institution which allowed sub-Saharans to make spurious claims about “police brutality.” The Board had been established during the liberal reforms of the 1960s and itself helped bring forth the crime wave in the first place.

Perot began calling for the end of the Board, taking considerable risks while making positive political contributions for whites. Perot quickly found himself in a vicious conflict with sub-Saharan race activists. He was surprised by this, however. He had always hired his employees based on merit and claimed that he had always supported black uplift, and couldn’t understand why his “teeth were getting kicked in” and that he was being labeled a “racist.” Perot failed to realize that sub-Saharans are comfortable with crime and sympathize with criminals, nor did he understand the problems arising from the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990. The US, supported by the United Nations, immediately declared Operation Desert Shield and began sending hundreds of thousands of troops to Saudi Arabia. It was the first major American military operation since the Vietnam War. Perot was against it from the start, believing that the war was really about control of oil. After the US expelled Iraq from Kuwait the following year, Perot said:

We rescued the Emir [of Kuwait]. Now, if I knock on your door and say I’d like to borrow your son to go to the Middle East so that this dude with 70 wives, who’s got a minister for sex to find him a virgin every Thursday night, can have his throne back, you’d probably hit me in the mouth.

Although this was hyperbole, he was nevertheless making a valid point. Americans, many of whom come from humble backgrounds, are often asked to serve in wars on behalf of nations whose main interest for the US is that they have good lobbyists in Congress. These same Americans are heavily taxed to provide foreign aid to wealthy leaders abroad. The US government likewise gives enormous economic subsidies to foreign commercial competitors in order to buy compliance with policies that the US government wants but which do nothing for ordinary Americans (or in some cases even harm their interests), such as supporting the industrialization of South Korea.

Perot declared his candidacy for President in February 1992, calling for volunteers to get him on the ballot in all 50 states. Volunteers indeed came forward and did so, and Perot climbed in the polls. His message was a mix of fiscal conservativism, social liberalism, rejection of free trade agreements, and funding for medical research to end the AIDS epidemic, which was then a major fear. Perot ran many infomercials, some of which were mean-spirited; in one, he claimed that Arkansas, where Bill Clinton was Governor at the time, was an insignificant entity compared to big corporations such as the ones he ran.

Perot’s campaign was disorganized, however, due to Perot’s management style and personality quirks. He didn’t want to pay the money needed for good advertising, and became fixated upon the false stories that the media spread about him. One such story claimed that he had dynamited a coral reef in order to make a channel for his luxury yacht. He obsessed about this for much longer than he should have.

Perot attempted to woo Democrats Paul Tsongas and Al Gore as his running mate. He eventually picked retired Vice Admiral James Stockdale, who had been the highest-ranking POW in North Vietnam, enduring torture and starvation. He had been forced to wear shackles on his legs for two years.

Perot pulled out of the race in the midsummer of 1992. He claimed that the Bush administration was threatening to release lewd “computer generated” photos of his daughter. He also believed the administration was spying on him. Perot’s biographer, Gerald Posner, believed that an unsavory character in the POW/MIA Movement was in fact behind it all. But it’s entirely possible that Perot’s claims were correct.

Perot changed his mind and returned to the race on October 1, 1992. He was allowed to participate in the debates by both the Democrats and Republicans. He did reasonably well in the first two, but appeared uncomfortable and confused in the third, where “undecided” voters asked “unscripted” questions. In the vice-presidential debate, Stockdale continually paced around the stage, complaining that his legs were bothering him. He had been given less than two weeks to prepare, and also appeared confused.[1]

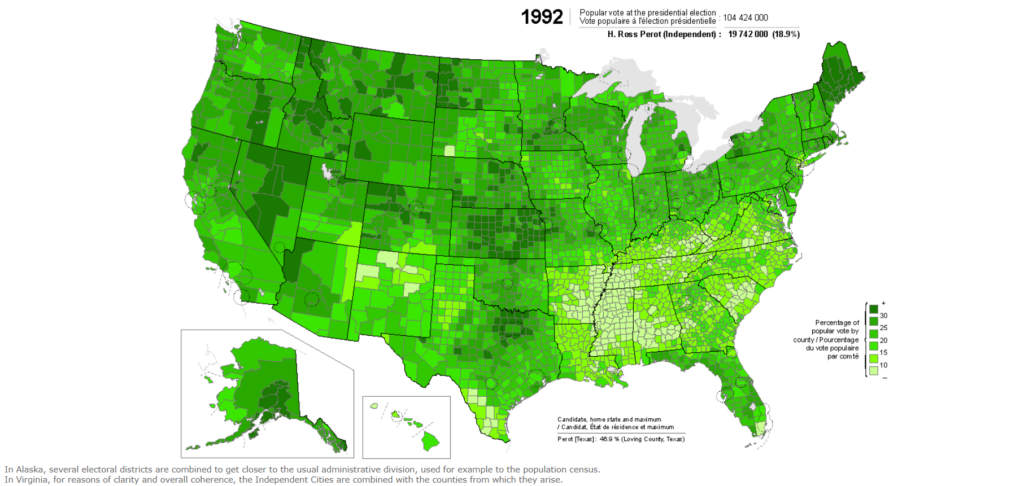

Ross Perot’s voters in the 1992 election. Perot failed to win any electoral college votes, but did have a remarkable showing.

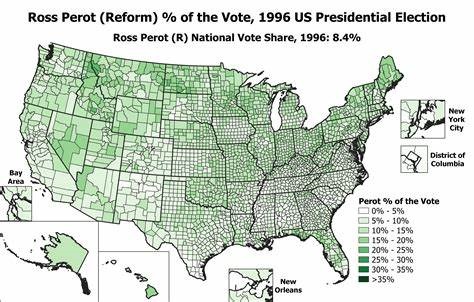

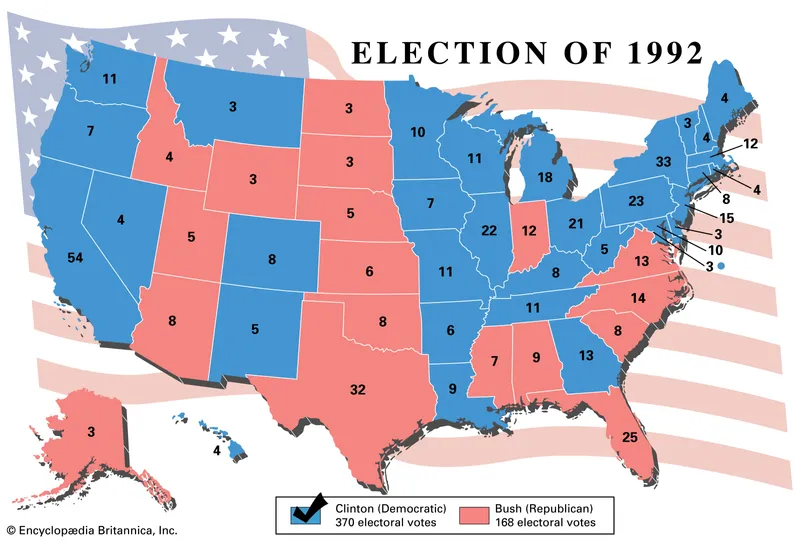

Perot won almost 19% of the vote on election night. It was an enormous showing for a third-party candidate who had run a less-than-ideal campaign. His ideas impacted the national conversation. Clinton didn’t entirely end the national debt, but he did achieve budget surpluses during his second term. Perot was unfortunately not able to stop NAFTA and the other neo-liberal free trade agreements, but his resistance to them set the stage for others to call for economic tariffs later. Perot ran again in 1996, but didn’t find the same level of success as in 1992.

The 1992 election is significant for the changes it brought at the margins of politics. White advocacy became part of the national conversation, as all the candidates –especially Pat Buchanan, who ran for the first time on an immigration restriction platform — expressed ideas of concern to white America specifically. All of the candidates were ultimately proved correct when they said that America was choosing a path of debt, deindustrialization, and anti-white racism which would ultimately destabilize America.

Note

[1] Both Stockdale and Perot became fodder for the late-night comedians.