Submerged Under a Black Sea: Paul Kersey’s Black Mecca Down

Paul Kersey

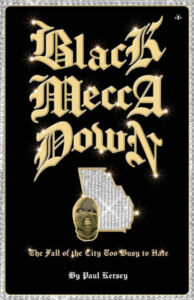

Black Mecca Down: The Fall of the City Too Busy to Hate

Allentown, Penn.: Antelope Hill, 2023

(originally published in 2012)

Paul Kersey has been focused on the effects of black majority rule in major cities across the United States for most of his writing career. He maintains a blog entitled Stuff Black People Don’t Like (SBPDL), currently hosted at The Unz Review, in order to document the criminality, incompetence, corruption, rapine destruction, and chaos that follow blacks wherever they go. It is bad enough when large numbers of dark denizens merely reside in a city; it is far worse when they are promoted far beyond their level of competency to leadership positions in public office. Black Mecca Down is a collection of essays pulled from the pages of SBPDL that focus on the precipitous decline of the once-idyllic city of Atlanta, Georgia. When the keys to the city — any city — are handed over to blacks, it is only a matter of time before it deteriorates into a derelict, disused ruin.

Blacks who attain positions of power in government and elsewhere seem to think that they should be immune to criticism. Paul Kersey has taken it upon himself to level a much-needed critique at a racial group that consistently and continually destroys whatever it touches. Not only are they incompetent, but their rampant nepotism and lack of any expertise whatsoever resigns any endeavour under their purview to the proverbial scrap heap. It is no wonder that a continent with unbound natural resources such as Africa remains a backward, Third World frontier slum when left to its native occupants. Without help from civilized peoples, it will remain that way in perpetuity.

Black Mecca Down, originally published in 2012, fell out of print. Thankfully it has been “resurrected and preserved” by Antelope Hill Publishing in a new edition. The eBook version is comprised of 45 chapters that originally appeared as individual articles in the pages of SBPDL during 2011 and 2012. They are thematically organized: each chapter documents instances where black incompetence, violence, cronyism, ethnocentrism, or a combination thereof contributed to Atlanta’s decline. From public transit, education, government, culture, criminality, and beyond, no area of the city has been beyond the reach of black malignancy. This new version also features footnotes and a bibliography. According to its author, Black Mecca Down is in many ways “a journey into why White people decided to create communities of their own, far from downtown Atlanta and, for a small period of time, devoid of Black residents.”

Kersey devotes the book’s first chapter to an examination of public transit in Atlanta, which is officially know as the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA). MARTA is colloquially known as Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta. He paints a picture of a public institution that is ostensibly tasked with providing transit to the city’s residents. In reality, however, it is less about mass transit and more about employing a vast horde of otherwise unemployable blacks in well-paid jobs, including lucrative leadership positions. Not only is the city’s leadership fraught with nepotistic race-based hiring, but so, too, is the transit authority. The system employs a unionized, black-mafia workforce that is not interested in giving up their monopolistic stranglehold on the system and its coveted jobs. This system, as you have already undoubtedly guessed, is also rife with crime. Kersey describes several violent incidents involving it based on reports in contemporary newspaper sources.

In the book’s second chapter, Kersey explores instances in the Atlanta educational system where teachers and other school officials were unjustifiably charged with racism. The author explains that unsubstantiated accusations of racism were often levelled at school staff or officials for frivolous, spiteful, or political reasons. In one instance, a teacher was charged with racism for not holding a celebratory reception for a black student who had been accepted to Harvard. While that may have been one of the purported reasons for the removal of a white principal and other staff, the real reason was racial cronyism and typical black academic underperformance.

Kersey reports in the book’s third chapter that even classical music and the racial makeup of student choirs are not beyond the reach of racial politics in Atlanta: “White people, no matter how much talent, are to be replaced in Black-Run America (BRA) with a continued energetic — and rapacious — drive for “diversity.””

The author’s approach to issues such as traffic and urban sprawl are refreshing, as they, too, are about race. Even though it is the elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about, Kersey is right to focus on what he calls Black-Run America (BRA)’s impact on all aspects of urban life. As the author sets out in his Introduction, the presence of blacks causes whites to take flight and set up communities of their own. Chapter Four documents yet another example of that phenomenon. Kersey cuts the Gordian Knot that is BRA and explains the real reason for Atlanta’s growing urban sprawl and related environmental degradation:

As has previously been stated here, Black people — and White people escaping from living near Black people — represent the greatest ecological threat to the United States. Some call it suburban sprawl; we simply call it escape from Black people (though you might hear neighbors, family members, or pundits call it “searching for good schools”). The Sierra Club published a report in 1998 where they labeled Atlanta as the worst city for “sprawl” (read: White people escaping from Black crime and property devaluations) . . .

The observational gems continue in Chapter Five as Kersey uses DeKalb County as a case study for the effect that large black populations have on property values. According to the author, “DeKalb County is the Prince Georges County of metro Atlanta for Blacks (54 percent Black and 33 percent White), considered by many to be the best place in the Black Mecca to call home.” Despite this glowing endorsement, the reality is much starker. Kersey goes on to point out that “DeKalb County saw eighteen thousand of its residents foreclosed upon in 2010, the third-highest number in Georgia, which contributed to the county seeing a drop in tax digest in early May of this year.” The author points out that the area’s affluent blacks, who are remunerated well beyond their competency, produce low-IQ progeny who underperform academically. This is reflected in their abysmal test scores.

Kersey points out an interesting correlation between academic performance and property values:

No one wants to mention the correlation between race and property value (in many cases — such as Fayette and Forsyth County — property value is tied to K–12 school system performance, which is directly tied to the race of the students enrolled), so it falls on SBPDL to point out that the halcyon days of unlimited growth in the Black Mecca are done.

You can buy Paul Kersey’s Whitey on the Moon here.

This chapter, and the book as a whole, can be summed up with by a single one of Kersey’s statements: “It’s time to call metro Atlanta for what it is: the black hole of America.”

No book that examines blacks’ deleterious effects is complete without taking a look at crime, especially murder. The book’s sixth chapter, entitled “The Atlanta Youth Murders and the Politics of Race,” describes the darkly hilarious period in Atlanta’s history when incompetent police work by Atlanta’s black officers led to an outrageous conspiracy theory about a white serial killer who was allegedly preying on black children. It is noteworthy that the incompetent black police leadership even resorted to employing psychics in order to hunt down this fictitious white perpetrator. Although a black criminal named Wayne Williams did indeed commit a few murders, there was no serial killer; it was merely another instance of blacks behaving like blacks. Kersey explains:

Blacks in Atlanta were whipped into a frenzy during this time period, attacking White firemen when they traveled into the areas where the “serial killer” was preying upon Black children, all because Organized Blackness had pointed an incriminating [finger] at a shadowy White person being behind these killings.

In actuality, it was just Black people killing Black people. It shouldn’t have taken a psychic to help Atlanta’s political class and police to figure this out, but then why would the federal government (Ronald Reagan authorized millions of dollars in aid to help combat the “serial killer”) and the nation’s media care about Black people randomly killing Black children? That’s not a juicy story!

Chapter 14 delves even further into the issue of black criminality. Some startling yet unsurprising facts serve as this chapter’s epigraph. Based on statistics from April 2011 through April 2012, blacks comprised 54% of the population of Atlanta, but were responsible for 100% of homicides, 95% of rapes, 94% of robberies, 84% of aggravated assault, and 93% of burglaries. Kersey goes on to examine the public statements, actions, and writings of a former judge in Atlanta, one Marvin Arrington, who is black. Arrington was appalled at black criminality and made attempts to reform black behavior. Although his intentions were good, the result was negligible.

Kersey then juxtaposes Arrington’s attempted reforms with examples of egregious black violence. The author documents, for example, the actions of one Brian Nichols, a black criminal, who in 2005 killed a judge, a court reporter, a federal agent, and a sheriff’s deputy in Atlanta, all in an attempt to wage a racial war on behalf of his perpetually oppressed black brethren.

Although Black Mecca Down documents black rule’s extremely negative consequences, it also offers glimmers of hope. Kersey makes the argument that white people have become aware that the artificial creation of a black ruling class through public sector sinecures and a myriad of other race-based incentives from hiring to housing has indirectly caused a reinvigorated white racial consciousness. In Chapter 31, entitled “Know Your Role and Shut Your Mouth: The Coming End of Black-Run America,” Kersey makes an astute and inspirational observation:

For too long White people in America have been told to know their role and shut their mouth. Pay taxes that go directly to fund the proliferation of a people whose only contribution to Atlanta (and America) has been crime, increased poverty, and the degradation of formerly great cities like Memphis, Birmingham, Baltimore, and Detroit.

Now, rumblings are being heard in the city too busy to hate. A fissure is developing of catastrophic potential.

With great power came the belief that the Blacks would forever play the race card and never expect “blowback” for race-based policies that require high taxation of the private sector (White people) to pay for an almost all-Black public sector.

With great power comes great responsibility.

The Blacks have reneged on this in Atlanta. Though it might not seem that obvious yet, the coming political war in Fulton County is the start of a series of clashes around the nation, as White people begin to slowly understand the burden of high taxation goes directly to pay for public jobs and services that go toward their dispossession.

Both Paul Kersey and Antelope Hill ought to be commended for putting Black Mecca Down back into print. The book is a prime example of how meticulous research along with references to copious primary and secondary sources helps can lay bare the issue of black dysfunction in a major American city. When no mainstream media outlets or commentators deigns to broach the crucial subject, Kersey delves into it.

I recommend Black Mecca Down to those readers and researchers who want to get to the heart of one of the key reasons for civilizational decline. There are many detailed observations made over the course of the book’s 45 chapters which demonstrate the author’s expertise. In this day and age, identifying the major sources of the problem is half the battle. Not only has Kersey done so in spades, but he is also providing hope for the future.