The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

2,398 words

The 1893 World’s Fair, also known as the World’s Columbian Exposition, was held in celebration of the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus. Best known for its magisterial fairgrounds, the Fair was a landmark event in American history and showcased a large array of cultural and scientific achievements. It attracted an audience of over 27.5 million over the course of six months and exerted a significant influence on American culture.[1] The Fair was one of the world’s greatest achievements and a testament to the greatness of American civilization — as well as the foibles that contributed to its decline.

Chicago was proposed as a candidate for the Fair’s location on account of its abundance of available land and its proximity to the West, and after several rounds of voting in Congress, it was selected to be the host city. Jackson Park and the surrounding environs were chosen as the site. Daniel H. Burnham, a prominent Chicago architect, was selected as Director of Works and assembled a team of American architects, including Richard Morris Hunt, George B. Post, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles McKim, Robert Swain Peabody, Solon Spencer Beman, Louis Sullivan, and others. The exhibitions were overseen by the Smithsonian Institution. Ordinary Americans were given the opportunity to participate in preparing the exhibits via World’s Fair committees at the state and county level.

In advance of the Fair, Chicago organized a series of Columbus Day ceremonies in late October of 1892. The official Columbus Day parade stretched nearly ten miles, with 16 to 20 people marching in a row. The festivities included performances by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and a 5,500-voice choir. The orchestra performed George Chadwick’s Ode for the Opening of the World’s Fair, which set to music a poem by Harriet Monroe entitled “Columbian Ode.”

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here.

At around this time, Francis J. Bellamy, who was in charge of the Fair’s planning committee, had the idea of devising a flag salute — the Pledge of Allegiance — for use in Columbus Day ceremonies in public schools across the country coinciding with the Fair. The pledge was published in the Youth’s Companion, a children’s magazine Bellamy co-edited with James B. Upham, in September 1892. (The recitation of the pledge was accompanied by the “Bellamy salute,” which was replaced by the hand-over-heart gesture during the Second World War due to its resemblance to the Nazi salute.)

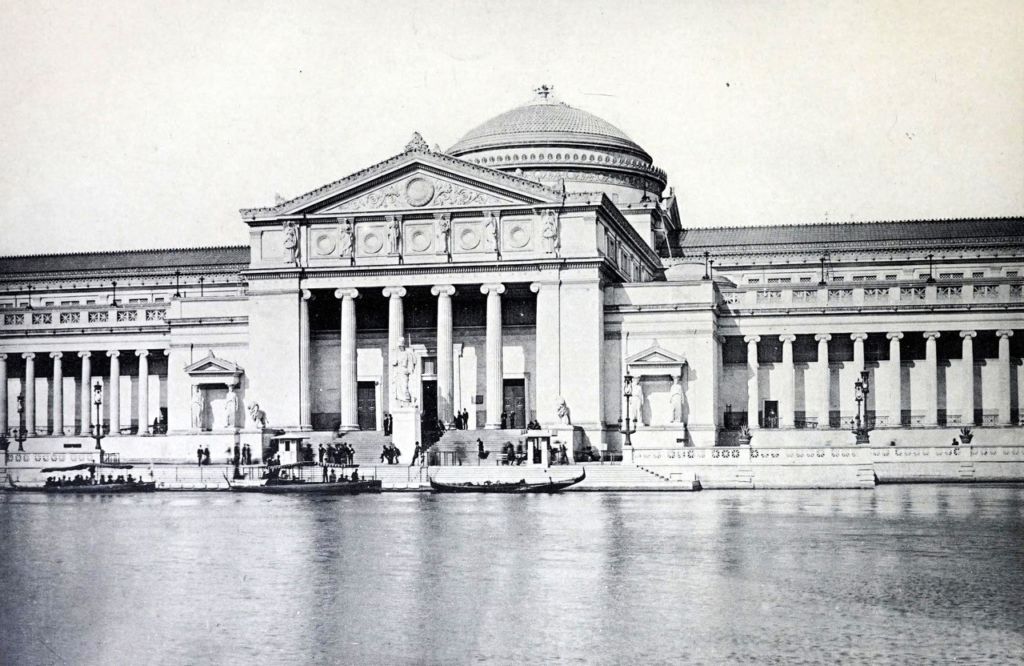

The Fair’s centerpiece was the “White City,” a complex of monumental neoclassical/Beaux-Arts structures with gleaming white façades. (The line “thine alabaster cities gleam” from “America the Beautiful,” which was written shortly after the fair took place, is an allusion to the White City.) At the heart of the White City, the “Court of Honor” was a large reflective pool in which stood a colossal bronze statue: The Republic by Daniel Chester French, depicting a figure representing America. Standing opposite from The Republic was an elaborate fountain piece by sculptor James MacMonnies, a student of Augustus Saint-Gauden, that depicted Columbia enthroned upon a barge rowed by figures representing the arts, science, industry, agriculture, and commerce. Each of the “great buildings” was dedicated to a different area of human achievement, with an emphasis on the sciences and industry. The buildings’ cornices were all uniform in height, creating a harmonious and symmetrical landscape. The White City’s architectural splendor, grand boulevards, parks, and Venetian-inspired lagoons and gondolas were intended to evoke the great cities of Europe. Daniel Burnham studied architecture in Paris, as did a number of the architects he hired (McKim, Hunt, Peabody).

The White City is credited with inaugurating the short-lived City Beautiful movement, which sought to beautify American cities and cultivate civic virtue among Americans through architecture characterized by order, harmony, and grandeur. Shortly after the Fair, Burnham, McKim, and Olmsted worked on the McMillan Plan, which entailed redesigning the National Mall according to the ideals of the City Beautiful movement in a manner reminiscent of Versailles. Burnham also went on to create a plan for the city of Chicago in 1909 based on the principles of the City Beautiful movement.

The finest of the “great buildings” were Hunt’s Administration Building, an imposing Beaux-Arts structure with a gilded dome at the center of the White City, and Charles B. Atwood’s neoclassical Palace of Fine Arts, which was made of brick and still stands today (unlike virtually all of the other structures erected for the Fair, which were built with cheaper materials in the interest of efficiency and were subsequently destroyed). Other buildings of note included Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building, a proto-modern polychromatic structure known for its golden arch; Henry Ives Cobb’s Fisheries Building, which was designed in the style of Spanish Romanesque architecture and featured capitals ornamented with whimsical depictions of marine life; A. Page Brown’s California Building, a notable example of California Mission Revival architecture; and Kirtland Cutter’s Idaho Building, a rustic cabin whose design and interior prefigured the American Arts and Crafts movement.

Approximately 50 foreign nations and colonies were exhibited in the Fair, 18 of which were represented by pavilions. The most notable among these were France’s elegant Beaux-Arts pavilion; England’s Tudor-style pavilion, which contained an exact replica of the dining room at Hatfield House; Germany’s pavilion, a composite of German architectural styles over the centuries; Norway’s pavilion, a reproduction of an eleventh-century Norse stave church; and Japan’s pavilion, a replica of a temple built in 1052 (which is thought to have contributed to Frank Lloyd Wright’s interest in Japanese architecture). There were also celebrations that commemorated the contributions of foreign countries — Germany, France, Norway, etc. — to the United States.

In honor of Columbus, the fair contained an exact replica of the Convent of La Rábida, where Columbus stayed for two years before finally obtaining Queen Isabella’s sponsorship for his voyage, as well as replicas of the ships of his original expedition, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. The replica of the convent contained numerous relics pertaining to Columbus, including the original copy of his contract with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

Constructing the buildings was a monumental undertaking, particularly given the stringent deadlines faced by the Fair. Nearly “20,000 tons of iron and steel and 30,000 tons of staff, many thousand tons of glass, and about 70,000,000 feet of lumber” were used in the creation of the main buildings. About 12,000 to 14,000 men were involved in the construction process.[2] The total costs of the construction of the fair, $27,245,566.90, significantly exceeded the initial estimate, necessitating federal assistance. In August 1892, Congress issued $5 million worth of bonds to the World’s Columbian Exposition Corporation.[3] The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building alone, the largest roofed structure ever erected, cost $1.5 million to build.[4]

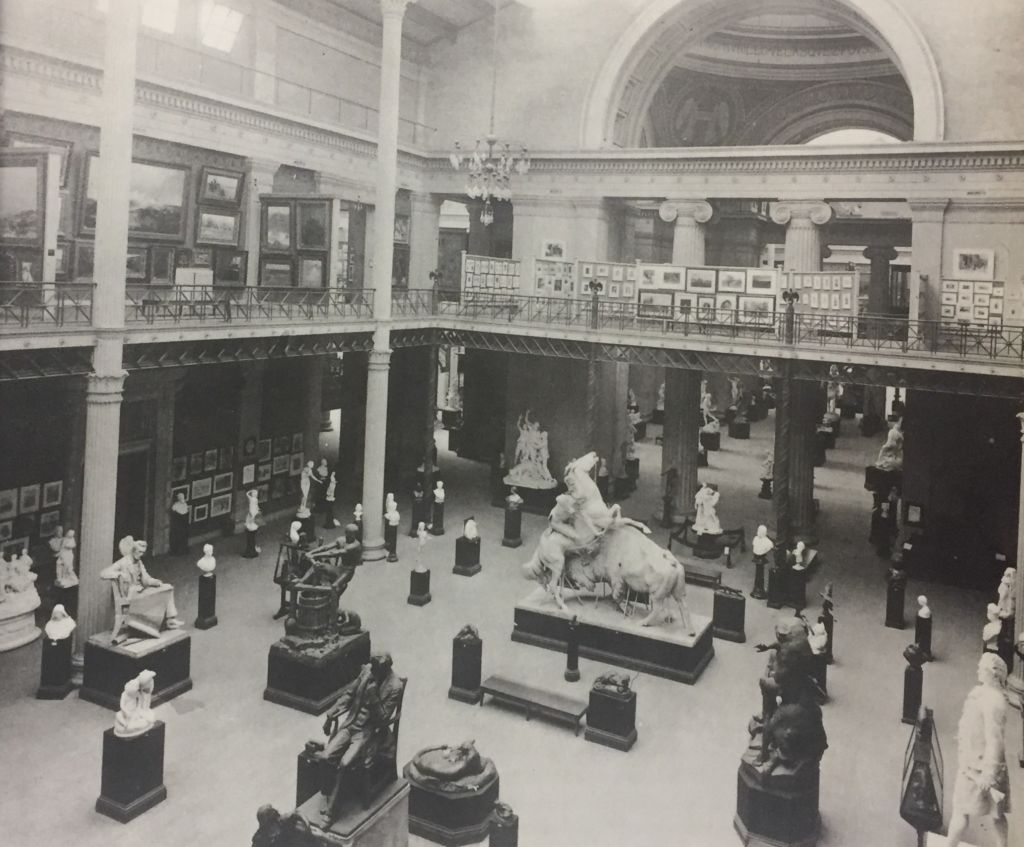

Beyond its impressive architecture, the Fair boasted the largest collection of American art ever assembled. The artworks were displayed in the Palace of Fine Arts. Stylistically, they were quite diverse:

. . . one could sample the dispassionate realism of Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Charles F. Ulrich, and Frederic P. Vinton or the cloying sentimentality of William T. Smedley and S. Seymour Thomas. The rural world could be experienced in the American scenes of Eastman Johnson, as well as the Barbizon-inspired portrayals of peasants by Edward E. Simmons and Charles Sprague Pearce. The crisply contoured renderings of F. D. Millet and Frederick James were given equal billing with the bravura brushwork in portraits by John Singer Sargent and William Merritt Chase. The highly narrative work of Thomas Hovenden found a home here, as did the allusive imagery of H. Siddons Mowbray and Thomas W. Dewing. Palettes ranged from the sober and restrained of men like Stacy Tolman and Charles T. Webber to the fresh, brighter hues of J. Alden Weir and John H. Twachtman.[5]

The Fair focused on American art created since 1876, but it also included late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century American art, as well as nineteenth-century European art from private collections in America. The total number of paintings and sculptures on display was four times as large as the collection at the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition.

Though the Fair’s artistic offerings were concentrated in architecture, painting, and sculpture, music was not absent from the festivities. Theodore Thomas, conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, oversaw the Fair’s musical activities. Concerts of popular music were held daily at noon and were free of charge. From May until August, orchestral concerts were held regularly in the Festival Hall, which sat 5,200 people. The Boston Symphony Orchestra and the New York Symphony Orchestra performed, as did several choral societies.

America’s scientific achievements and industrial might were likewise on full display. The Fair’s exhibitions featured locomotives, phosphorescent lamps, an electric automobile, the world’s first fully electrical kitchen, electrical devices developed by Nikola Tesla, and the world’s first Ferris wheel, which was invented by George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr. for the occasion. Electricity — supplied by the Westinghouse Company — was used throughout the Fair on an unprecedented scale. The electric power plant in Machinery Hall included 16 generators and was the largest power plant in the world.

You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here.

The Fair held congresses on a range of academic subjects, including philology, literature, history, folklore, psychology, philosophy, and the sciences: “no aspect of human endeavor was ignored in the proud assertion of America’s global ascendancy.”[6] It was here that historian Frederick Jackson Turner first presented his famous paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.”

The Apollonian grandeur and cerebral offerings of the White City contrasted with the ethnographic villages and amusements that lined the mile-long Midway Plaisance, a park perpendicular to Jackson Park. The Midway Plaisance featured displays of people imported from around the world clothed in their country’s attire in villages evocative of their homelands and provided light entertainment in the form of gypsy bands from Hungary, African drummers, acrobats, and Oriental belly dancers. A particularly popular attraction was the “Street of Cairo,” which featured a mosque and fountain, exotic dancers, camels and donkeys, and street scenes (e.g., wedding processions) characteristic of the city. The purpose of the Midway Plaisance was in part to entertain attendees, but it was also to educate the public on racial differences. “What an opportunity was here afforded to the scientific mind to descend the spiral of evolution,” remarked one newspaper, “tracing humanity in its highest phases down almost to its animalistic origins.”[7]

The White City was conceived as a celebration of white male achievement and framed civilization as a white male endeavor. One poet described the White City as “A Vision of Strong Manhood and Perfection of Society.”[8] The juxtaposition of the White City and the Midway Plaisance deliberately highlighted the contrast between white manliness (The Century Dictionary: “the highest conceptions of what is noble in man or worthy of his manhood”) and more primitive forms of masculinity.[9] Non-whites were virtually absent from the White City and were confined to the Midway Plaisance. Women’s creations were featured in a modest exhibition hall on the periphery of the White City.

The tragedy of this moment in American history is that the ideology propped up by the Fair arguably contained the seeds of the demise of the very civilization it upheld. It embraced the view that civilization progressed linearly from savagery to a state of perfection, the latter of which was equated with commercial abundance. The vast quantity of items and goods on display reflected the American ethos of conspicuous consumption and the popular infatuation with prosperity theology, which was then at its height. By the late nineteenth century, the “acquisitive society . . . had taken form, already augmented by a superabundance of goods and by that transformed and growing institution of affluence, advertising.”[10] From 1880 to 1890, the value of advertisements in the American press increased by nearly 82% ($39,136,306 to $71,243,631).[11] America’s preoccupation with generating wealth was a boon to the nation at first, but had the eventual result of undermining American greatness and abetting the forces of globalization.

Many progressive reformers believed that white people were morally obliged to elevate primitive peoples. Since they equated civilization with prosperity, entering foreign markets was “part of an inexorable civilizing process that America had a duty to perform.”[12] The burgeoning ideologies of globalism and free-market capitalism thus went hand-in-hand with white supremacy. (This illustrates the fact that race realism can be made to align with a wide range of positions and must be supplemented with a more complete ideological program, as I argued here.)

One is reminded of Thomas Cole’s The Consummation of Empire, to which the White City bears a strong resemblance. The Fair represented America at its ripest and most resplendent, and, as in the painting, its lavish decadence portended a future characterized by destruction and uncertainty.

The fairgrounds vanished just as quickly as they had been erected. Some buildings were demolished immediately following the Fair; the rest were wiped out in a series of fires. The image of the Republic standing amid the ruins of the Court of Honor is a poignant symbol. The only structures that have survived to the present, besides the Palace of Fine Arts, are the World’s Congress Auxiliary Building; the Norway pavilion; the Maine State Building; the Dutch House; and the Viking, a replica of the Gokstad ship constructed for the fair.

The Republic pictured in 1894. She was set on fire in 1896 in order to pave the way for renovating Jackson Park.

The enduring fascination with the Fair lies in the fact that it represented America’s promise as a young nation and was a brief moment of respite before “the onrush of time and events thrust American civilization irrevocably across the threshold of history into the cataclysmic twentieth century.”[13] It provides a glimpse into what America once was, and what it could be again.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] David F. Burg, Chicago’s White City of 1893 (Lexington, Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky, 1976), p. 72.

[2] Ibid., p. 56.

[3] Ibid., p. 57.

[4] Ibid., p. 63.

[5] Carolyn Kinder Carr, “Prejudice and Pride: Presenting American Art at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition” in Revisiting the White City: American Art at the 1893 World’s Fair (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1993), p. 98.

[6] Elizabeth Broun & Alan Fern, “Introduction,” ibid., p. 15.

[7] Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), p. 35.

[8] Ibid., p. 32.

[9] Ibid., p. 27.

[10] Burg, p. 12.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Robert W. Rydell, “Rediscovering the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition” in Revisiting the White City, p. 38.

[13] Burg, p. 205.