Jack London’s The Iron Heel as Prophecy

Part 1 of 2

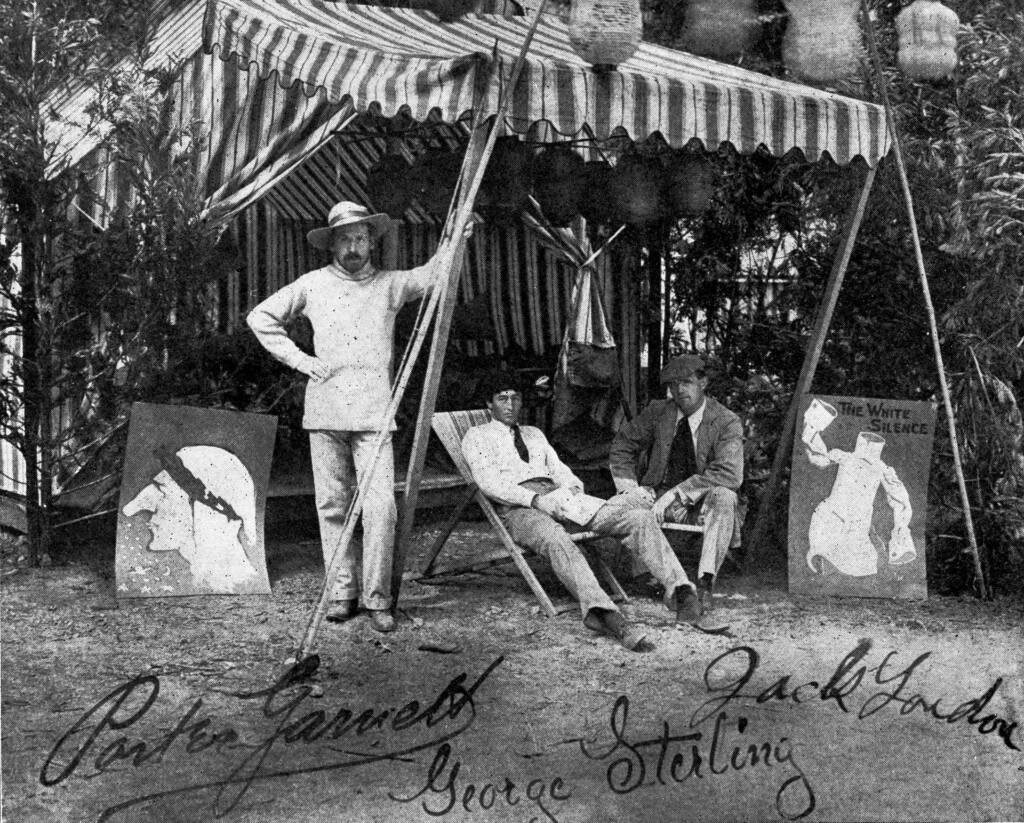

The celebrated American writer Jack London is best known for stories of adventure such as White Fang, The Call of the Wild, and “To Build a Fire” — the last being a chilling tale, indeed. Some of his writings were informed by his political views, a synthesis which is quite rare nowadays. London made an early contribution to dystopian literature with The Iron Heel, a novel about the formation of the leviathan state. Written in 1907, it precedes the more famous works by Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, and even Yevgeny Zamyatin. Since it’s explicitly revolutionary and socialism features heavily in it, it’s hardly surprising that it is the author’s pinkest novel. Still, don’t let that deter you.

They don’t make radicalinskis like they used to

The Left used to be a lot more sensible before cultural Marxism appeared. In Jack London’s time, they were agitating for collective bargaining and the 40-hour work week. Today’s Leftists persuade kids to get sex changes — whenever they’re not rioting over the dead black criminal of the month. They also used to have substance and panache. They weren’t squidlings and crybullies moaning about “microaggressions” while cowering in safe spaces. It’s hard to remember the last time Leftists had cojones. The Viet Cong, perhaps. But rest assured that had anyone asked Jack London what his pronouns were, he would have responded as if his interlocutor had just stepped out of a flying saucer.

In the days of yore, some socialists were actual manual laborers, which was the target audience for their ideology. They weren’t a bunch of activists pretending to be professors, scientists, and journalists. Who knew, right? Before Jack London became a famous author, he was known for a number of interesting pursuits: oyster poacher, sailor, extreme Schwartzfahrer, Alaskan prospector, and so on. He earned his proletarian street cred, such as by working literally all day in a canning factory for ten cents an hour. (He unfortunately drank up his wages at the local watering hole for ten cents a beer, but that’s another story.) His socialist views were influenced by Karl Marx and the now-obscure American bestseller, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward.

Better yet, he was pro-white. That may be quite a surprise given his ideology. But he was very much at odds with the absolute egalitarianism which is now almost universal among the Left. For instance, take the following:

Socialism is not an ideal system, devised by man for the happiness of all life; nor for the happiness of all men; but it is devised for the happiness of certain kindred races. It is devised so as to give more strength to these certain kindred favored races so that they may survive and inherit the earth to the extinction of the lesser, weaker races.

You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here.

Whoa, dude, totally deplorable! Although it’s been observed that being a pro-white Leftist isn’t necessarily a contradiction, I have to wonder where they all are. Ages ago, most of them ditched the proletariat for the cultural Marxist bandwagon. Jack London in his final year could see where this was going, writing in 1916, “I am resigning from the Socialist Party, because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle.”

The last Leftist head of state who showed so much as a scintilla of regard for white people was a literal tankie who is now as dead as disco. There’s an obscure anecdote in which Leonid Brezhnev once mentioned to Margaret Thatcher that he was concerned about the survival of the white race. The Iron Lady’s reaction was to pucker as if she’d chugged a liter of lemon juice, clutching her pearls and collapsing on a fainting couch left over from the Victorian era. (I’m exaggerating Maggie’s snippy reaction, but not by that much.) The problem is that, despite this unexpected moment of clarity, Comrade Brezhnev never got around to using his vast powers as Prime Pinko Poobah to do anything for the white race. That was a lost opportunity, to say the least. On the other hand, Margaret Thatcher’s posture toward her white citizens didn’t even rise to benign neglect, failing to meet even Soviet standards. What a typical mainstream conservative!

The story’s prescience

The Iron Heel has some interesting parallels with The Turner Diaries, one of William Pierce’s naughty novels, so it’s possible there might have been some literary influence. For example, several footnotes explain facets of the contemporary society in the novel for the edification of the imagined reader in the far future who, thanks to the protagonist’s sacrifice, lives in a sane and normal society. The Turner Diaries does this as well, though treads lightly with this element.

The footnotes in The Iron Heel make for a sort of ongoing Greek chorus throughout the book. Here’s one:

Though, like Everhard, they did not dream of the nature of [the oligarchy], there were men, even before his time, who caught glimpses of the shadow. John C. Calhoun said: “A power has risen up in the government greater than the people themselves, consisting of many and various and powerful interests, combined into one mass, and held together by the cohesive power of the vast surplus in the banks.” And that great humanist, Abraham Lincoln, said, just before his assassination: “I see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country . . . Corporations have been enthroned, an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money-power of the country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until the wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed.”

It sounds as if there’s been a problem that was long in development and of which these famous figures were aware. This footnote, which appears earlier, is quite remarkable:

Even as late as 1912, A.D., the great mass of the people still persisted in the belief that they ruled the country by virtue of their ballots. In reality, the country was ruled by what were called political machines. At first the machine bosses charged the master capitalists extortionate tolls for legislation; but in a short time the master capitalists found it cheaper to own the political machines themselves and to hire the machine bosses.

The author therefore correctly anticipated in 1907 how the money side of the Deep State — in recent times more delicately called the “donor class” by the mainstream media — would get its hooks into the leadership of both parties. When 1912 rolled around, the globalist cabal got its first President, thanks to Bernard Baruch’s recruitment efforts. The text implies that the public later figures out that two-party politics is a sham. But given the way things really went, Joe Sixpack still doesn’t quite understand that it’s as fake as professional wrestling. It took another century for The System’s mask to start slipping, and the work to educate the public isn’t yet done.

One more interesting aspect is that the story’s Iron Heel is an oligarchy that emerges as an outgrowth of big business interests that got together and decided to start running the show. That’s remarkably similar to how things developed in relation to contemporary globalism. It’s as if the author was light years ahead of everyone else.

Also, the two principal metropolises of the future world socialist utopia are Ardis and Asgard. (The evocative names alone certainly sound spiffier than dilapidated Leningrad, barely-functional Havana, or starving Pyongyang.) These are described as similar to the pleasure cities envisioned by H. G Wells. They were built during the oligarchy’s reign using exploited labor, but are presumably kept up well, and more wonder cities were built after the Revolution. Comparing this to our present real-world conditions, that’s quite unlike the widespread neglect of old buildings found in the Second World, alongside examples of fashionably ugly pinko architecture.

Opening matter

In the edition of The Iron Heel I own, Maoist luminary H. Bruce Franklin presents an Introduction. He was a professor (what else?) who began his academic career at Stanford. When a colorful mishap followed his involvement in student activism, he moved on to Rutgers. Comrade Franklin’s analysis seems a bit dodgy. He equates the Iron Heel’s capitalist cabal with fascism, naming “Italy, Spain, Portugal, Rumania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Germany” as examples. Silly pinko! I can’t speak to all of these — I’ll confess ignorance about Bulgaria’s interwar politics — but overall, that’s nonsense.

For one thing, portraying Corneliu Codreanu as a capitalist toady would be laughably absurd. That’s certainly not what he was about. Moreover, in Romania, as well as neighboring Hungary, the “bourgeois capitalists” were the Jewish minority that had monopolized the lucrative professions through ethnic networking while shutting out actual Romanians and Hungarians from these trades. (As the lyrics of one Legionary song went, “They make us paupers in our own home.”) Moreover, as Captain Codreanu documented quite extensively, the Jews were manipulating local politics, with lots of public officials taking payola. Even the King of Romania was quite notoriously kissing up to them. The Communists, for their part, didn’t mind the bougie types too much, for (((obvious reasons))), despite all their endless talk of class warfare.

Moreover, the fascists generally stood in opposition to the early version of the Deep State. That was comprised of the Anglo-Saxon powers, as the old cynic Josef Goebbels called them, and the international banksters that the early WASP globalists were already sucking up to. This was analogous to the Oligarchy in The Iron Heel, and ultimately this combined white collar mafia evolved into The System which we all know and love today.

Comrade Franklin continues:

London’s white supremacist ideas are surprisingly almost as absent as his male supremacist notions . . . But of course London, like his contemporary socialist comrades, was still a long way from understanding that the non-white peoples of the world were destined, in the second half of the twentieth century, to lead the revolutionary forces.

It’s true that the cultural Marxists abandoned the proletariat after failing to get them on board. After that, they changed their focus from class struggle to race agitation, among other identity-group grievances. (This is what made modern Leftists so screwy, and also lately led to the wonders of Clown World.) Still, it’s pretty silly to imagine that types such as Frantz Fanon, Angela Davis, and Robert Mugabe were calling the shots in the inner corridors of the international Leftist establishment. That would be like claiming that golems such as Ibram X. Kendi outrank George Soros.

This is followed by Jack London’s own Foreword. The protagonist, Ernest Everhard, is one of the major figures in the resistance against the Iron Heel. (That’s obviously a symbolic name, though the author was related to the real-life Everhard family.) The story is told by his wife, née Avis Cunningham — a cunning bird, indeed. It describes the Oligarchy as a monstrous offshoot of late-stage capitalism, unanticipated and unexplainable by theory, which interrupted what should have been a smooth transition into a socialist “Brotherhood of Man.” It’s fairly clear from this much that the author was acquainted with Marx’s dialectical materialism.

The Foreword gives away the outcome: The Second Revolt that they were organizing is violently suppressed. Further uprisings occur, leading to seven centuries of conflict before the Iron Heel is overthrown for good. Hopefully, this won’t end up being too prophetic. A century of globalist misrule has been quite enough, and the very idea that the Deep State might still exert its vampiric presence in some form even a century from now makes me thoroughly sick.

The education of a socialite

The story begins with a wealthy businessman who likes to conduct bull sessions at home with various guests. One day, he brings home a unique visitor — a proletarian — who is presented to the other guests rather like an exotic creature imported from afar. This, of course, is Ernest Everhard. The businessman’s daughter, Avis Cunningham, watches with interest as this prize specimen debates a roomful of clergymen. He naturally wins handily and leaves these great minds befuddled. (I have yet to see a philosophical novel where a protagonist loses a political argument.) He more or less calls them out for navel-gazing and says that Christianity turns a blind eye to the plight of the workers.

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here.

This was written back in the day when factories really did have awful working conditions. The United States solved that problem to a large degree through trade unionism. This worked for several decades, until the globalists did an end-run strategy by closing the factories and shipping them to Third World sweatshops where they could pay the workers peanuts again.

Ernest’s points do involve some cherry-picking. For example, Catholic social doctrine is a major exception to what he says, having established the idea that employers have a duty to provide decent working conditions and living wages. This includes the Rerum Novarum encyclical, a key document for distributism and other Third Position economics.

All told, Ernest seems rather like a Leftist Howard Roark, the protagonist of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, if that can be imagined. The heiress is attracted to his alpha traits. She later debates him herself, and he replies by using the poignant example of someone who worked for his father’s company and lost an arm in the machinery. (I gather from one of the footnotes that this may have been based upon a real incident.) He tried to sue for damages, but it came to nothing. She investigates further and discovers that the company bribed the witnesses, and even the plaintiff’s attorney. Basically, there ain’t no justice.

She soon finds out that journalists are presstitutes beholden to their corporate masters, and that editors will spike any story that doesn’t fit The Narrative. In fact, she finds out that she’s been taught a bunch of lies about the way society works. Is it me, or is this starting to sound pretty familiar?

I was confronted by the concrete. For the first time, I was seeing life. My university life, and study and culture, had not been real. I had learned nothing but theories of life and society that looked all very well on the printed page, but now I had seen life itself.

That’s sort of a red pill moment, isn’t it? At the least, it’s hardly unlike people today coming to the painful realization that their sociology professors fed them a load of crap, and that journalists are bullshit merchants as well.

The gathering storm

Ernest is later invited to attend the Philomath Club, a very hoity-toity West Coast gathering: “Its members were the wealthiest in the community, and the strongest-minded of the wealthy, with, of course, a sprinkling of scholars to give it intellectual tone.” (It’s possible that this is a reimagined Bohemian Grove, a very colorful club which inducted none other than London himself.) This led to a debate in which Ernest flummoxes a high-powered attorney in the opening act. The rest goes something kinda sorta like this:

Everhard: You capitalists have used remarkable advances in technology to increase production, while hogging all the surplus profit for yourselves, leaving the working class more impoverished than cavemen.

Capitalist: Yeah, so?

Everhard: We’ll overthrow you “let them eat cake” types, after which you’ll have to acquaint yourselves with brooms and mops.

Capitalist: Bring it on.

Everhard: Come Election Day, we’ll vote you bums out of office.

Capitalist: We’ll stop the count at 3 AM in key swing states and stuff the ballot boxes with just enough “mail-in ballots” to make our brain-damaged, girl-sniffing figurehead “win.” What are you going to do about it, huh?”

Everhard: [Says bad-optics things.]

All told, it has its moments, such as Ernest sticking it to the lawyer for repeatedly changing the subject. Moreover, he says that the ruling class is good at business, but stupid about everything else. I would concur that being skilled in a particular form of commerce doesn’t always translate into expertise in other subjects, such as statecraft.

This is followed by a chapter called “Adumbrations” — basically the gathering of shadows. First up, Avis’ father receives a “Come to Jesus” talk from the President of his university, calling him out for his radical connections and suggesting a two-year sabbatical. (A Berkeley professor getting scolded for hanging out with Leftists? After what happened to the place in the 1960s, that didn’t age well!) Far more prophetically, Ernest says:

Never in the history of the world was society in so terrific flux as it is right now. The swift changes in our industrial system are causing equally swift changes in our religious, political, and social structures. An unseen and fearful revolution is taking place in the fibre and structure of society. One can only dimly feel these things. But they are in the air, now, to-day. One can feel the loom of them — things vast, vague, and terrible. My mind recoils from contemplation of what they may crystallize into. . . . I mean that there is a shadow of something colossal and menacing that even now is beginning to fall across the land. Call it the shadow of an oligarchy, if you will; it is the nearest I dare approximate it. What its nature may be I refuse to imagine.

The footnote I quoted at the beginning appears immediately following this, illustrating what some famous predecessors such as Abraham Lincoln and John C. Calhoun had observed already in development. In retrospect, this much turned out to be chillingly accurate.

In another subplot, a bishop appears at a conference to announce that he sheltered some hookers in his large palace. He recommends that others take in hookers and thieves as well in order to reform them. (From personal experience, I can say that the results usually aren’t good. Long story.) As Ernest predicts, the press doesn’t report a word the bishop says, thanks to the corporate editors. Not long after, he gets tossed into the loony bin to adjust his attitude. Later, when he sells his fortune and begins helping the poor, he gets sent back to the nuthouse.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.