The Zen Way in France, by Guillaume Durocher

I discovered Zen a few years ago. I had never encountered anything quite like it. I had been possessed by the frenetic, over-stimulated nature of life today, which we are all familiar with, particularly in the age of the Internet and social media. I was both restless and aimless, and consumed by the petty anxieties about professional life, where ultimately very little is really at stake.

And then I found Zen, where one is invited to sit down and . . . nothing. How shocking to be told that one should stare at the wall for an hour. And yet, I was not ‘bored,’ and I often came back to the meditation hall.

During zazen, seated meditation, one sits down in a particular posture (legs cross in half or full lotus, back upright, chin tucked in), one follows the breath, and one learns to let go of thoughts – not to suppress – but simply to be detached from them, to watch them go by, like clouds drifting across the sky.

If you ever meditate, you’ll soon find that you cannot repress your thoughts even if you try, that you have little control over your thoughts. The mind is ever-buzzing with our daily plans, daily worries, daily duties, daily frustrations, past memories, and future fantasies. In fact, one can be rather embarrassed at the obsessions which return again and again, surging forth from our subconscious, like strange fish regularly jumping out of the troubled waters of a pitch black lake.

‘Doing nothing’ in zazen actually then entails quite a few activities, quite a few exercises for the mind. One trains oneself in:

- Patience

- Self-control

- Steadiness of will (maintaining posture, returning to the breath)

- Detachment from our thoughts (and thereby, from all things)

- Self-awareness (observation of our own consciousness and glimpses of our subconscious)

- And, finally, the quieting of the mind

Actually, to speak of ‘training’ is in one sense improper, for zazen is practiced without any goal at all. It is a gratuitous waste of time. This is an exercise in self-lessness. The ego is not suppressed, but seen in a different light, as inseparable from the cosmos, which itself, in one sense, exists only through our particular subjective consciousness. Perfect interdependence.

There are many scientific studies claiming that meditation has beneficial effects on mental health and even certain cognitive abilities. I cannot say whether these are credible or not. Perhaps Zen meditation is a mere placebo – a ritual and exercise which can still appeal to and convince the secularized European – but then there are also plenty of studies showing that placebos, in many cases, can help people overcome pain and even depression. I have no doubt that the communal rituals and chanting of religions also can have powerful psychological effects.

All I can say for sure is that the effects for me have indeed been powerful. With regular practice, your way of being during zazen redounds on your way of being in daily life. One is more detached, more tolerant, more sovereign in the face of circumstances. One is less dispersed and has greater self-control. After one meditative retreat, I must say I felt genuinely transformed: I was no longer at war with the world, my contempt for certain colleagues subsided and I was even genuinely happy to see them, I was no longer offended by ‘wrong opinion,’ I was able to genuinely dialogue with others. When you really are happy to see someone, they will be similarly happy to see you. If you work from their starting point – rather than expecting to impose your own – you can actually converge and build something together. In short, you become again a member of your community, while keeping your individuality. You become, at your humble level, a node of positivity and power in this often senseless world.

This feeling faded after a couple weeks. Had I achieved genuine insight? Had I really been more open-minded and altruistic? Or was this a kind of mystical blindness, an indeed altered mental state which, like some drug, led to a merely superficial bliss? I cannot say.

I can say however that I have faith in Tradition and in the accumulated experience of our ancestors. Spiritual practice is by no means an Oriental monopoly. From the ancient Pythagoreans and Stoics to the medieval Christians, Europeans have worked to alter and train their minds to better reflect the order of the cosmos, the divine. It is only we Moderns who have faltered in this respect. Spiritual exercises gave our ancestors strength to survive and thrive, to persevere in their actions and their principles, in a world which was much more brutal than that of today.

Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy – which has invariably resonated much stronger with me than the Modern – is deeply concerned about the cultivation of the soul. As perfectible beings with a degree of agency, our mind is what we should improve, our actions (which are the only things we might otherwise control) will then necessarily improve. The rest is of no concern to us. For the Ancients, there were not ten thousand ways of producing a good human being: one needed to be well-born, to have a good education, to be socialized with the right people, and train every day. Modern science has added nothing to these insights. As Pierre Hadot has shown, ancient philosophy was deeply concerned, from Pythagoras to Julian, with self-perfection through “spiritual exercises.”

I hasten to add that, unlike many meditators, I personally have no need for any supernatural explanations for spiritual practice’s positive effects. (Which, conversely, does not mean I deny the possibility of the supernatural.)

In this I follow the ancient Stoics, whose practice did not depend on the gods existing or not. Stoic philosophers such as Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius simply observed: almost everything in this world is outside of my control, I should then focus on what is in my control, namely my own state of mind, and focus on entirely detaching myself from the rest and perfecting my own will. (The doctrine of samurai, as most powerfully expressed in the Hagakure, is by the way quite similar in this respect.) Thus, the Stoics developed spiritual exercises (usefully summarized by Massimo Piggliucci), such as premeditating on the ordeals you will face, contemplating the impermanence of things and the vastness of the cosmos, and being ever aware of our inevitable impending death.

Stoicism however always remained the private practice of a part of the Roman elite, never systematically followed, nor spread to the masses. Stoicism could not survive the emotional power and mass appeal of Christianity. Buddhism by contrast offers the strange sight of a movement, in fact a variety of different schools, which can appear either religious or philosophical. Beyond exceptional individuals, a spiritual practice cannot be systematic if it does not take on a religious form. Where the Stoic exercises remain very ‘cognitive’ and ‘cerebral,’ too diverse and wordy in a sense, in zazen there is the purest philosophical exercise: the unflinching contemplation of the void.

The pious Muslim solemnly takes time five times a day to think about his community and his fundamental values. What do you do?

In material terms, spiritual practice is about working on the subconscious, about internalizing certain truths. One can easily know, abstractly and verbally, that man is a social, perfectible, psychological (or spiritual), limited, and mortal being. But does one really know this? Does one live in consequence? It seems to me that this is what all the traditional religious practices deeply express, each in their particular way, with their own particular (often significantly different) inflections.

Personally, I can say that zazen has helped me preserve my sanity in this world of lies. Hear the words of Lord Gautama said in India twenty-five centuries ago:

Just as a lotus,

Sweet-scented, ravishing,

Grows on a heap of refuse

Flung on the high road,

So a disciple of the Awakened One,

Shines out through wisdom

Among the blind multitude,

The refuse of beings.

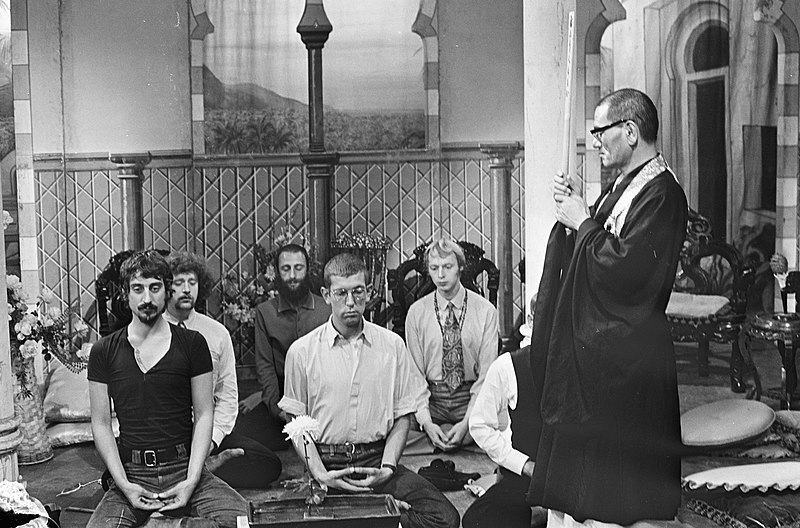

Zen was first brought to France by the Japanese monk Taisen Deshimaru. France, and Europe in general, were then enjoying unprecedented economic growth and a profound social revolution breaking down traditional religious and familial hierarchies. The newly freed, equalized, and comfortable individual did not find satisfaction however, but remained enervated and restless, and continued to crave even more freedom (understood purely as ‘freedom of choice’), equality, and comfort. It was in this spiritual morass which Deshimaru arrived in 1967, rapidly gathering a large following through his remarkable personality and single-minded focus on zazen seated meditation.

I did not meet Deshimaru myself so I cannot say much of him. His achievement was remarkable however, initiating tens of thousands of Europeans to the practice of Zen and attracting an incredibly devoted circle of, mostly French, followers. These followers built a Zen temple on the beautiful grounds of the Gendronnière (southwest of Paris in the Loire Valley) and established some 200 Zen dojos across Europe. Today one can find a community of meditators in most medium to large European cities. These followers have also produced an extensive literature on Zen tradition and experience. Deshimaru’s achievement is all the more striking in that . . . he did not speak French and barely spoke English! (On which, see an interview of his uncertain English peppered with French and Japanese.) A Zen saying reported by Deshimaru: What is eloquence? Stuttering.

Deshimaru thought that France, with its sophisticated tradition of philosophical introspection, was well-suited to receive the teachings of Zen. Zen was presented to the skeptical and ‘rational’ French as something “not a religion” but a kind of spiritual/philosophical UFO. There may be a secret kinship between French and Japanese culture in this respect, the embrace of impermanence. As the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran wrote:

France’s divinity: Taste. Good taste.

According to which the world – to exist – must please; must be well-made; consolidate itself aesthetically; have limits; be a graspable enchantment; a sweet flowering of finitude.

Deshimaru was deeply inspired and invigorated by what he found in Europe. While the practice of Zen had become sclerotic and conventional in Japan – the ossified monastic orders cut off from society, the temples passed on from father to son as a lucrative funeral business – Deshimaru was deeply impressed by the earnest and dedicated practice of young Westerners. He even charged them with an awesome and flattering mission: that these Europeans might be the spark for a global spiritual renewal.

This is not the first time the harsh truths of Buddhism have resonated with Europeans. T very first representations of the Buddha are in fact Hellenic statues, crafted by Greek or Greek-influenced artisans, after Alexander the Great’s armies conquered northwest India. European traditionalists, whether Dominique Venner or Julius Evola, have typically had a high opinion of Zen and of Japanese culture in general. I’d even argue George Lucas’ original Star Wars trilogy owes a great deal to Zen and the samurai, in particular the notion of detachment from both emotion and conscious reason, so as to tap into a more spontaneous primordial intuition . . .

Zen promises no miracles, no salvation. There is a Tradition, passed on from master to student, but there is no submission to hierarchy or dogma (an old Zen saying: “If you see the Buddha on the road, kill him”). There is only the embrace of existence in the here and now, the active observation of the mind-universe, the chaotic ungraspable flux of consciousness from moment to moment. From this, a cultural and even biological fecundity might arise, but that is incidental. Zen and Japanese culture are intimately interrelated. It is not hard to see how the same culture which produced Zen, with its spiritual discipline and frank acknowledgment of impermanence, also produced the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, the samurai, and . . . the kamikaze.

I do not know what all this will lead to. Zen remains a marginal phenomenon in Europe, but is participating in a wider spiritual renewal. As Christianity decayed in the 1960s, already Westerners were craving some kind of spiritual sustenance. This demand was met by Jon Kabat-Zinn’s ‘mindfulness,’ essentially a medicalized and secularized repackaging of traditional Eastern meditative practices (Kabat-Zinn is a marketing genius in this respect). I have the hope that genuine spiritual practice might heal the European soul. That it might allow for dialogue between the dominant mentality and suppressed one. Time will tell.

The European is a wretched creature today. He or she is dedicated either to nothing or to the lowest ideals, wracked by bitterness and ressentiment. And yet, I have seen these Europeans – perfectly godless and lucid – bow their heads three times to Gautama, thus reverencing a great teacher, the cosmic reality, and indeed the shard of divinity within themselves . . .

And for that I say:

Hail Buddha!

Notes

“Dojo” in Japanese means “place of the way,” the way in question not necessarily being a martial art.