Remembering Philip Larkin

1,747 words

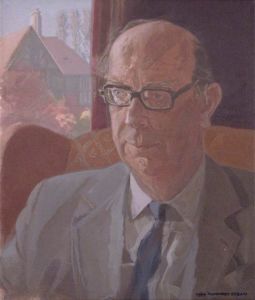

English poet, novelist, and critic Philip Larkin was born on this day in 1922. The only son of a prosperous middle-class family in Coventry, Larkin earned his BA from St. John’s College, Oxford, with First Class Honors in English. Then Larkin trained to become a librarian, which became his life-long career, ending up as librarian at the University of Hull.

Larkin wrote constantly but did not publish much. He was a perfectionist and destroyed many of his unfinished works. His first book of poetry, The North Ship, was published in 1945. He then published two novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947). The publication of his second collection of poems, The Less Deceived (1955), made his name. It was followed by The Whitsun Weddings (1964) and High Windows (1974). His Collected Poems (1988) was a literary sensation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Larkin also wrote critical essays and reviews of both literature and music, becoming an increasingly acerbic opponent of modernism. He was the jazz critic for The Daily Telegraph from 1961 to 1971. His writings on jazz were collected in All What Jazz: A Record Diary 1961–71 (1985). His literary criticism was collected in two volumes, Required Writing: Miscellaneous Pieces 1955–1982 (1983) and Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Book Reviews 1952–1985 (2001). Larkin also edited The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse (1973), which reflected his broadly anti-modernist and populist outlook.

Larkin was influenced by Yeats, Auden, and Hardy. He disdained poets like Pound and Eliot who wrote works that only Ph.D.s can decode. Instead, Larkin wrote poems that more or less rhymed in simple, direct, colloquial English, which made him immensely popular, even though his poems deal with bleak topics in a disturbingly frank manner. Newspaper critics and the public generally loved Larkin. Academics tended to be frosty, however.

Larkin shied away from literary celebrity but won many honors, including the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. When Poet Laureate Sir John Betjeman died in 1984, Larkin was offered the position but declined. He felt that his work had been declining. The next year, he died of cancer at the age of 63.

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here.

The posthumous Selected Letters of Philip Larkin, 1940–1985 (1992) was greeted with the sound of sharpening knives in academic quarters, for they revealed that Larkin was quite politically incorrect. He expressed racist and sexist sentiments with brutal and sometimes hilarious frankness. The screeching became louder when Andrew Motion’s biography Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life appeared in 1993. As more biographical evidence came to light, it became increasingly clear that Larkin was not just politically incorrect but also a man of the Right. Larkin was not, however, a conventional Tory. He was an atheist. He was a jazz aficionado. He never married but had a number of long-term relationships with women, sometimes running concurrently.

But for all that, Larkin despised egalitarian leveling in its moderate liberal and militant Leftist forms. He was an early noticer of the Great Replacement and the cultural and social decline it brought: “I find the state of the nation quite terrifying. In 10 years’ time we shall all be cowering under our beds as hordes of blacks steal anything they can lay their hands on.” He supported Enoch Powell for prime minister, and hilariously announced that he aspired to be the Enoch Powell of jazz criticism, whatever that entailed. Larkin, moreover, was an English nationalist. He rejoiced in his language, culture, and history which connected him to such giants as Shakespeare. Then there were the revelations that his father was a highly literate Nazi sympathizer, who twice attended the Nuremberg Rallies and introduced his son to the works of such artists of the Right as Ezra Pound and D. H. Lawrence. Recently, it has emerged that Larkin’s longtime partner and heir, Monica Jones, was wise to the racial and Jewish questions and sympathetic to the National Front. Then there’s “How to Win the Next Election” (1966):

Prison for strikers,

Bring back the cat,

Kick out the niggers,

How about that?

Trade with the Empire,

Ban the Obscene,

Lock up the Commies,

God Save the Queen.

Come to think of it, I really wish Larkin had taken the Poet Laureate position and lived to compose odes to the likes of Princess Di, Tony Blair, Stephen Lawrence and his mother Doreen, Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon, or Meghan Markle, now Duchess of Sussex.

It is an evil, but a necessary one, that for many of you, your introduction to Larkin’s poetry was “How to Win the Next Election,” above, rather than his bleak but utterly brilliant “Aubade,” which is one of the most powerful poems of the 20th century:

“Aubade”

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

— The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused — nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear — no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

Here is Larkin’s reading:

Like Nietzsche, Larkin was an atheist, but although he felt that the death of God might be liberating to some, he feared it would also be bestializing to the masses.

The sexual revolution said that the key to happiness was stripping sex of morals, conventions, and the threat of reproduction and making it “recreational.” Like Houellebecq, Larkin sensed that the sexual revolution may be more destructive in the end than Bolshevism.

“Annus Mirabilis”

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) —

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Up to then there’d only been

A sort of bargaining,

A wrangle for the ring,

A shame that started at sixteen

And spread to everything.

Then all at once the quarrel sank:

Everyone felt the same,

And every life became

A brilliant breaking of the bank,

A quite unlosable game.

So life was never better than

In nineteen sixty-three

(Though just too late for me) —

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

In “High Windows,” Larkin pairs sexual revolution and atheism. But are they really forms of liberation, or merely giving way to gravity? Does the big slide lead to happiness, or behind the promise of happiness, is it the void that beckons?

“High Windows”

When I see a couple of kids

And guess he’s fucking her and she’s

Taking pills or wearing a diaphragm,

I know this is paradise

Everyone old has dreamed of all their lives —

Bonds and gestures pushed to one side

Like an outdated combine harvester,

And everyone young going down the long slide

To happiness, endlessly. I wonder if

Anyone looked at me, forty years back,

And thought, That’ll be the life;

No God any more, or sweating in the dark

About hell and that, or having to hide

What you think of the priest. He

And his lot will all go down the long slide

Like free bloody birds. And immediately

Rather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.

If you wish to read Larkin, begin with The Complete Poems of Philip Larkin, ed. Archie Burnett (2012).

If you wish to sample his critical writings, read Required Writing and All What Jazz. Also see our own Frank Allen’s “Philip Larkin on Jazz: Invigorating Disagreeableness.”

The best Larkin biography is James Booth’s Philip Larkin: Life, Art, and Love (2014).

Despite the controversies about his politics, Larkin has not yet been cancelled. In 2003, Larkin was chosen by the Poetry Book Society as Britain’s best-loved poet of the previous 50 years. In 2008,The Times of London declared him Britain’s greatest post-war writer. In 2010, the city of Hull marked the 25th anniversary of his death with the Larkin 25 Festival, which included the unveiling of a life-size bronze stature. In 2015, it was announced that Larkin was to be memorialized in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey. If Larkin is cancelled one day, though, we will be happy to welcome him into the Valhalla of Artists of the Right.

Other Writings on Larkin at Counter-Currents:

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.