The Story of Black Barbie, by Anastasia Katz

Black Barbie (2023) is a documentary on Netflix about Barbie dolls and their psychological impact on black children. The first half tells the history of these dolls. As a Barbie collector, I found it interesting, even though I have never bought a black doll. The second half is about Mattel’s DEI efforts and how children view Barbie in relation to their racial identities. There is a lot of woke posturing: “still so much work to do.” Writer/director Lagueria Davis — black, of course — interviews former Mattel staff, celebrities, and academics.

History of black Barbie

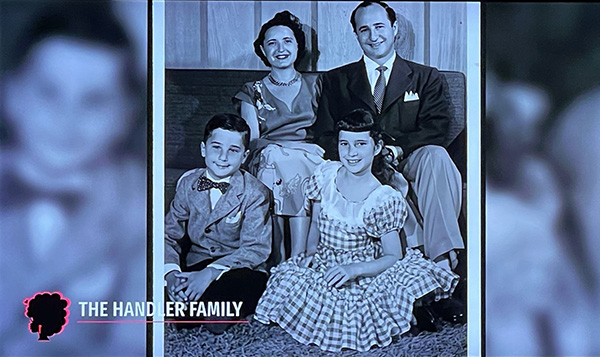

The film barely covers the history of the white Barbie doll, so I will. The Mattel toy company was started in 1945 by Ruth and Elliot Handler. It made such toys as the Uke-A-Doodle (1947) and advertised on “The Mickey Mouse Club” in the 1950s.

On a family trip to Europe, the Handlers’ 15-year-old daughter Barbara saw a doll named Bild Lili in a shop window in Lucerne, Switzerland. She liked the doll because the clothing could be changed, but the only way to get another outfit was to buy another doll. Mrs. Handler bought her four.

When they returned to America, Ruth Handler began working on a doll for which there were different clothes and accessories. She named the doll “Barbie” after her daughter, and the Barbie doll debuted at the 1959 American International Toy Fair in New York City. (In 1961, the Ken doll was introduced, named for the Handlers’ son.) The box proclaimed Barbie as a “teen age fashion model.” The first Barbie came dressed in a bathing suit, and there were 23 outfits available. Barbie became Mattel’s best-selling toy, and today Mattel is valued at $6.3 billion.

Black Barbie begins with actress Ashley Blaine Featherson-Jenkins, known for Dear White People, spinning a fantasy about how she imagines black Barbie was created. She imagines a lone, black employee at Mattel telling the white executives, “This is not right, there’s nobody who looks like me here,” and then convincing the whites to make a black doll, even though the whites think it won’t make a profit. “It took said black person to keep telling them of the value that it had,” Mrs. Featherson-Jenkins imagines.

The real story is that the Handlers never hesitated to make black dolls. Mattel’s staff is also very unlike the depiction in last year’s hit movie Barbie: only straight white men, from cubicle to board room, except for one Hispanic receptionist. The company has had black and female creative staff for decades, and today it has a global head of DEI.

Black Barbie insists that it is important for black girls to have dolls that look like themselves, but the two women interviewed about life before black Barbie did not recall a desire for black dolls. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA) got white dolls from a charity for Christmas when she was a child. “There were no black dolls. . . . We didn’t think a lot about it at that time,” she admits, but later she “began to understand how important it was to have a black doll.”

Director Lagueria Davis’s aunt, Beulah Mae Mitchell, played with white dolls as a child and Miss Davis asks if she wanted a black one. She replies, “It didn’t occur to me; it was just a doll.” She remembers that the black dolls available at the time “were like Aunt Jemima. They didn’t have no pretty dolls.”

Mrs. Mitchell was hired by Mattel in 1953 to work on the assembly line, and she helped to make the original Barbie. She says Mrs. Handler had a good rapport with workers and would ask if they had suggestions. Mrs. Mitchell says she suggested a black Barbie. Mrs. Handler replied, “Well, good. We’ll see.”

In 1966, Mattel released a white doll with blonde and brunette variants named Francie, marketed as “Barbie’s cousin.” The next year, a “colored” version of Francie was released, which had darker skin but the same features. In 1968, Mattel released a doll named Christie with more African features.

After the Watts Riots of 1965, (called the “Watts Rebellion” in Black Barbie), a black man named Lou Smith began “Operation Bootstrap” to give job training to unemployed blacks in south Los Angeles.

Mr. Smith’s son says, “My father . . . decided to make black dolls that look like black people, and he talked the owners of Mattel out of $200,000 to start a toy company,” which he called Shindana.

Mrs. Mitchell remembers that Mattel sent its own employees to the Shindana factory, “to show them how to make black dolls.”

In the 1970s, Shindana made a black Barbie-like fashion doll called Disco Wanda. The company had a profitable run before closing in 1983. (The movie notes only that other companies had started following its “business model.”)

In 1976, a fashionable young black woman named Kitty Black Perkins answered an ad for a designer job at Mattel. “I went for the interview and I left there thinking I have to have this job. I can’t do anything else.”

She was given a doll and asked to make an outfit for it; Miss Perkins came with six designs and was hired. Beulah Mitchell — the assembly-line worker — was promoted to receptionist in 1969. African American Studies professor Patricia Turner claims that Mrs. Mitchell “laid the groundwork for Kitty [Perkins] to come in as a professional. They’re acclimated to the presence of a strong, competent black woman in the workplace. That enabled the next step, which is a strong, competent black woman as a designer. Whether or not Kitty would have been welcome had Beulah not been there, I’m not sure you can say.”

Mrs. Mitchell raves about Miss Perkins: “We were proud of her! Because she drove a sports car, and she matched our idea of Barbie. We thought she was a black Barbie!”

Miss Perkins was assigned to create the first black version of Barbie. The documentary does not explain why Mattel needed a black Barbie in addition to the black Christie doll.

Miss Perkins wanted a distinctive doll. White Barbie had long hair and full-skirted costumes, so Miss Perkins designed a doll with short, curly hair and a slim-flitting dress. She took inspiration from singer Diana Ross. “I wanted her to be the complete opposite of Barbie. . . . I gave her bold colors, bold jewelry, short hair and a wrap skirt that could actually show skin.”

A black woman designer who specialized in hairstyles worked with Miss Perkins to give the doll a “short natural.” There was also a black sculptor who finished black Barbie’s face.

“The skin was a little bit lighter than the darkest that we could have done,” Miss Perkins says, “It was really a preference, and I preferred that color.”

The doll was released in 1980, 21 years after white Barbie’s debut, and little black girls were delighted. The box claimed, “She’s black, she’s beautiful, she’s dynamite!”

Mrs. Featherson-Jenkins says: “Crowning the doll as Barbie . . . was telling the world black is beautiful, too. I’m so grateful that we are included now in the legacy of that.”

“I knew that black Barbie was different,” Miss Perkins says. “I never realized the magnitude.” The doll’s success led to other lines of black dolls, anniversary editions, and re-releases. However, at the time of the doll’s release, not everyone was pleased. Miss Perkins remembers that a focus group of black mothers felt their children were being slighted because the doll did not have the long hair and full dress that white Barbie had. Mattel consulted a child psychologist who agreed. “But when the child psychologist found out that the designer was black, it all went away,” Miss Perkins recalls.

The documentary points out that the first black Barbie had not been marketed well and did not have a television commercial. However, Miss Perkins’s next black doll, Shani, debuted with much fanfare at a New York toy convention in 1991. There was a fashion show with models dressed like Shani and her friends. The Village Voice “went on page after page” with coverage. It was the first black doll line that had its own TV and print ads.

In 1996, Miss Perkins hired a black woman protégé who went on to design her own line of black dolls. Miss Perkins retired after 28 years with Mattel.

The doll experiment

Black Barbie next discusses the doll study conducted by black psychologists Drs. Kenneth Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark in 1947. They put two white and two brown dolls side by side on a table and asked children which dolls they preferred. The majority of black children said they liked the white dolls more. When asked which dolls were more like them, the black children sometimes expressed annoyance. In a taped segment, Mr. Clark is shown saying, “Some of those children looked at me as if I were the devil himself for putting them in that predicament. It gave psychologists understanding of the terrible damage that’s done to human beings by racial rejection.”

Needless to say, Black Barbie does not tell the true story of the Clark experiment. The Clark doll test strongly influenced Supreme Court justices in Brown v. The Board of Education (1954), which ordered school integration. Clark reported that if he showed black and white dolls to black children attending segregated schools and asked them which doll they liked better, many picked the white doll. He argued to the Court that this proves segregation breeds feelings of inferiority. He failed to mention that he had shown his dolls to blacks attending integrated schools in Massachusetts, and that even more of these children preferred the white doll. If his research showed anything, it was that integration lowers black self-esteem. His court testimony was dishonest.

In Black Barbie, Congresswoman Maxine Waters said the doll experiment “sent shockwaves through the black community . . . . Little black girls did not have self-esteem, did not think of themselves as beautiful, and would prefer to have a white doll.”

For Black Barbie, Dr. Amirah Saafir, professor of child and adolescent studies at Cal State Fullerton, revisits the Clark doll experiment by having non-white children play with Barbie’s current line of multiracial dolls. She says her study was inspired by the Clark doll study, “but not modeled after it.” After the children are interviewed in groups of three, Dr. Saafir has a black panel of experts interpret their responses.

The first group of children — all non-white — appears to be in the first grade. The children were asked which is the prettiest doll. One black girl replies, “The prettiest one to me is Brooklyn, because she has black skin like all of us.” She adds that she does love blonde Barbie’s outfit and hairstyle. However, a little boy says blonde Barbie is prettiest — “Because of her dress and shoes.”

When asked if they have heard of race, the first graders say, “No, what do you mean?” A group of three third-grade girls thinks the word “race” might be a foot race. In the oldest group — perhaps fifth graders — a girl says race means “racism:” “when people judge you for the color of your skin and how you look.”

Asked what their families tell them about being black, a first-grade girl says, “Always be a beautiful black queen.” Another says, “My mom says I should be proud of my black skin and if anyone else who doesn’t have black skin asks, ‘What’s black girl magic?’ I’ll say, ‘Oh, it’s nothing that you would understand.’ ” A fifth-grade boy says, “It’s not okay for cops to be mean to us and put us on the ground because we didn’t do anything.”

Antwann Michael Simpkins of UCLA’s Department of Sociology says, “Barbie is not going to do anything that you [the parent] have not done. . . . I don’t want to place onto Barbie the work that we should be doing as a society to dismantle. To me, the ultimate end work of authentic diversity, equity, and inclusion is to disrupt the violent institutions, the violent structures, the violent dolls, doll-like worlds that exist because of the long legacy of colonialism.”

Mason Williams, Mattel’s global head of DEI, is proud that his daughter views all Barbies equally. “We have the whole diaspora [sic] of colors, skin tones, body shapes. . . . I would bet that if you grab 30 kids right now, and you ask, What does Barbie look like? You might get 26 different answers.”

The study shows that blonde Barbie’s legacy looms large. To the question, “Which one would you say is the real Barbie?” every group identifies the blonde doll.

Dr. Saafir, who did the study, thinks it’s because blonde Barbie is still presented as “what’s normal, what’s ideal, what they should be striving for . . . . The societal structure of power and privilege, where black people are at the bottom, is clearly articulated to kids.”

There is another explanation. Barbie is no longer just a doll; she is a media product. The animated TV series Barbie: Life in the Dreamhouse (2012–2015) and Barbie: Dreamhouse Adventures (2018–2020) was about blonde Barbie, her three younger blonde sisters, and of course blond Ken, who is always portrayed as a goofy good friend, not a boyfriend. A first-grade girl in Dr. Saafir’s study says that blonde Barbie is the real Barbie because “that one has her own show.”

Some black mothers in the documentary aren’t happy that their children are watching cartoons with a white main character. Stylist Rebecca Gross says that the black characters in Dreamhouse are always sidekicks. “It’s like a present-day version of the exclusion that was happening when there wasn’t a black Barbie doll.”

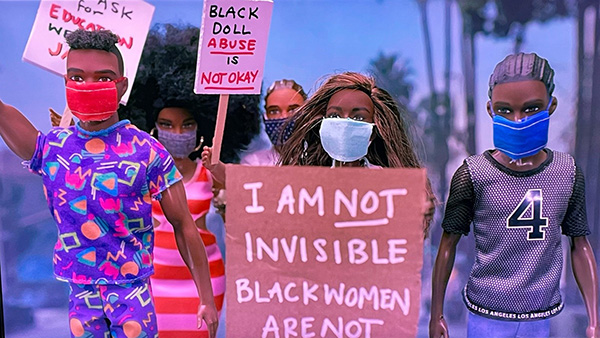

Barbie is also on social media; there is a Barbie YouTube channel that shows Barbie’s vlogs. Mattel hired a black woman to write a vlog episode “to talk about the issues that were happening in 2020.” Barbie’s black friend Nikki says “beach security” stopped her for peddling children’s colored stickers on the beach, but did not stop Barbie. Barbie adds, “That’s not fair, because that means white people get an advantage that they didn’t earn, and black people get a disadvantage that they don’t deserve.”

Actress Gabourey Sidibe commented, “I love it if it works. If the little white girls that look up to Barbie . . . start pointing out racism when it’s happening and standing up for their black friends or their Latino friends.” Ironically, she also says, “I’m sad that kids can’t just be kids.”

Since 2011, Mattel has released at least one Barbie movie per year, each about a line of dolls, and white Barbie is always the main character. In 2021, black Barbie became her co-star.

In Barbie: Big City, Big Dreams, white Barbie attends a summer arts program in New York, where she meets a black girl whose name is also Barbie. To avoid confusion, they decide to go by the names of their hometowns; white Barbie is “Malibu” and black Barbie is “Brooklyn.”

Malibu and Brooklyn compete for a solo performance in Times Square. Blonde Malibu struggles with everything while black Brooklyn performs effortlessly. Malibu is out of step in dance class and her guitar strings break. Malibu’s suitcase on wheels rolls away and Brooklyn catches it with a graceful ballet move.

Yet Malibu practices, and by the time the two perform a duet in the finale, they are equally competent. The “experts” in the documentary disapprove of Malibu’s determination to do well, and of the story of strangers becoming good friends. They want Brooklyn to win the solo spot and upstage Malibu. They think whites always get a leg up when they compete against better qualified blacks.

Mattel’s DEI head explains that Brooklyn will be “getting a whole universe for herself,” including a TV show and a line of Brooklyn dolls. A black teenage girl who is interviewed says she doesn’t think the Brooklyn-centered show will be as successful “because we live in, I don’t want to say it” — encouraged by her mother to go on — “we live in a predominantly white world, and most successful people that you think of is white, right?” She thinks whites won’t watch an all-black program.

Director Davis wonders, “Are we really doing the job if it’s 2024 and our kids still think the world is predominantly white?” A pie chart appears, showing that whites are a world minority.

Being Barbie’s friend wasn’t enough; being Barbie’s namesake wasn’t enough; being Barbie’s co-star wasn’t enough. Black Barbie has to be center stage, and the white doll that built the Mattel empire needs to be pushed out.

As I watched interviewees talk about how important it was that Mattel released a black doll named Barbie, I remembered that when I was a little girl, the first thing my friends and I did with Barbie dolls was make up new names for them. Any child had the power to name a black Christie doll or a Shani doll “Barbie” if she wanted. Blacks can never be satisfied.