Some Aspects of the Yellow Peril

Street, Shanghai, a few years ago. China ain’t what it used to be. Getting rid of Mao did the trick. PhredFoto

1,716 words

Ages ago, for reasons I no longer remember, I was wandering across Asia and decided to spend some time in Taiwan. The Chinese interested me, and Taiwan was then as close as it was practical to get. Then, as now, the Chinese were thought by many to be exotic, inscrutable, devious, and unlike normal people such as ourselves. You know, opium dens, dragon ladies, assassinations by puff adder, that sort of thing. Given the importance of China today, the nature of these multitudinous people might bear thought.

As was commonly done in those days, I found a (very) cheap place to stay in the winding alleys downtown and settled in. Nice enough place, I thought, agreeable people, pretty girls. It is curious how unweird people turn out to be if you actually live among them, this being a principle I had discovered among the Thais, Viets, Mexicans, and Cambodians. I shared an apartment with another wandering young gringo, and a little Japanese mathematician named Sakai — ”whiskey well,” if I remember the characters of his name — and two young Chinese guys. One of them, Ding Gwo, played the guitar and wanted to be a rock star. The whole bunch were extraordinarily ordinary. The Chinese are in fact as exotic as potatoes. The kids act like kids anywhere, the women like women. They are not another species.

The girls dressed to be attractive and pretty, hardly a novelty among young women, and were often wildly successful. (Oriental women tend to appeal greatly to Western guys, the condition being known as “yellow fever” or “rice fever.” It is not a matter of sexual availability, the middle-class girls being less promiscuous than American, but just lovely and feminine. Chilly they were not.)

At night we sometimes went to a local hangout for the young — pretty much like any other, though more innocent than the American today: Taiwan was decidedly authoritarian and being caught with drugs would not have led to a happy ending. Dim lights, soft drinks, Western rock, and considerable flirtation. It could have been Memphis.

Exotic murderess girlfriend Chin Ping distracts Fred with humor while temple dragon sneaks up behind to bite his hand off. It’s how the Chinese are, crafty, and hang out with concrete animals.

I studied Mandarin hard on the principle that most things are possible with a combination of modest intelligence and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and in six months could communicate reasonably and slog my way through a pulp novel with lots of help from a dictionary. A Chinese dictionary is an adventure all its own. The school was Gwo Yu R Bao (romanization a jackleg mix of Yale and Wade-Gyles and god knows what else), literally Mandarin Newspaper, but it had a language school above. My teacher, Jang Lau Shr, was a mid-fortiesish woman who seemed quite old to me at the time. She was competent and likable, and not devious, sneaky, or mysterious. She probably didn’t have a single puff adder. I guess she hadn’t gotten the word.

When the government realized that I was a journalist of sorts, she was suddenly replaced by a very attractive young woman who I know damned well was from Guo Min Dang intelligence. Manna from heaven.

Sisters of Chin Ping, the Wiley Murderess. You could almost mistake them for, you know, just kids, unless you knew of their eerie genetic affinity for puff adders.

Several things I noticed, young and dumb as I was (the two conditions overlap greatly). Taiwan was not Uganda. At the time all manner of countries in the bush world had Five-Year Plans or the equivalent. These countries usually consisted of a patch of jungle, a colonel, and a torture chamber. Decades later, they would still consist of a patch . . .

Taiwan, then in the Third World — whatever that is — had an equally ambitious program of advancement. Perhaps it was for five years. It included the Jin Shan reactors, a new port, a steel mill, a major highway, and so on. Thing was, they were actually coming into existence. Later, for the Far Eastern Economic Review, I would interview the head of the nuclear program. Harvard guy. Later, on a press junket, I would visit many of the projects, such as the steel mill, which was in production.

With my honed capacity for recognizing the inescapable, I concluded that these people could get things done. Things like industry, organization, technology. That sort.

At some point I had passed through Hong Kong and concluded that it was New York with slanted eyes. The Chinese, I judged correctly though young and dumb, could play hardball finance.

And in the United States, Chinese students were reported to be doing very well at places such as MIT. Hmmm . . . What if that great American ally, Mousy Dung, stopped paralyzing the mainland and the world had to compete with all 800,000,000 of them?

We are finding out.

I loved the language, the characters that seemed almost to dance on the page in old, old documents in the national museum, which was filled with wonderful works of art saved from the Communists when Chiang fled to the island. I couldn’t begin to read them, of course. Modern Chinese is remarkably easy, however, provided you don’t want to read or write it, having none of the complexities of tense, mood, or person of, say, Spanish. It made people lots less mysterious to realize that they were not talking about the hidden Blue Jade Eye of God, worth millions and protected by a curse, but about Grandma’s congestive heart failure and what to do about it.

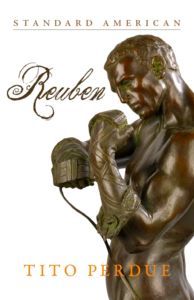

You can buy Tito Perdue’s novel Reuben here.

And, for a young man, there was practical Chinese: “Wo mei-you kan-gwo numma pyauliang-de syau-jye.”

On blazing hot evenings we wandered through the twisting lanes past rows of what appeared to be orange crates at which sat children doing their homework. Inside, they would have cooked. I thought this studiousness impressive, but had no idea how much it would later pay off at MIT.

A traffic overpass near where we lived had a steamy, enclosed food market beneath with stalls selling just about anything edible and some maybe not quite. We would go there for sheets of fried squid — ”you yu” — and fruit juice, the latter sold by a young woman who became a friend. We called her “Shwei Gwo Syau Jye,” or Fruit Juice Girl. Taiwan had not then become the economic Mighty Mouse that it is today, and most people, though not hungry, were poor. She spent long, long hours in her stall with a small, fluffy dog to keep her company. She had a subscription to Newsweek that she read to learn English and walked home with her dog every night, exhausted, to take care of a father of some 80 years.

She deserved better. There was a lot of that going around.

There were relics, fast disappearing, of the old China, more closely resembling the exotic image. In Wan Wha (“Ten Thousand Glories”) there was the street of the snake butchers, definitely memorable by night. At stalls live snakes, some of them deadly, hung by strings around their necks, if that is what snakes have. The proprietor on request slit a snake from head to tail, massaged the blood into a glass, squeezed the gall bladder into the mess, and sold it to, usually, a laborer to drink. Dwei shen-ti hen hau: Good for the body. Not mine, though.

At the time what was called Madame Chiang’s hotel was going up on a hillside. Most new buildings in Asia look like buildings in Philadelphia. This one was deliberately Chinese, and glorious. I had no idea that years later on a junket the Taiwanese government would put me up there, and several other reporters, for a week. Funny how things work.

I came to have immense respect for China as a civilization. Given the dismal record of immorality, poor judgement, and venality that is the baseline for humanity, China is impressive.

Among racial sites on the Web today, one frequently sees the assertion that Asians can copy but not invent. Maybe. There is a chain of thought that begins with “screwed up like a Chinese fire drill,” then, “Well, they can make pencils and toys,” (“Made in Japan,” remember?), then, “Okay they can make easy things like washing machines with white supervision,” and then, “Well, yes, they can assemble iPads, but can’t create anything.” Then, it turns out — as it has turned out — they are designing world-class supercomputers all of their own. Oops, heh.

On the one hand, the condescension sounds like wishful thinking. On the other, in painting for example, there is more creativity between the Impressionists and Klimt than in centuries of Chinese painting, which usually consisted of making copies of past masters. We had better hope.

Years later, on the junket aforementioned, my wife and I and our very small daughter came to Taipei and stayed in Madame Chiang’s. I don’t know how old babies are when they first sit up unaided, but that’s how old Macon was, because it is what she did. Anyway, we came into the lobby, Blonde Poof in arms. gorgeous vases on pedestals, columns in red lacquer, everything but the Empress Dowager, and they may have had her in a closet somewhere.

The staff, mostly young girls, came running over, charmed by anything so exotic and golden-haired. The Chinese can do many things, but golden hair isn’t one of them. They all wanted to look at this wonder child. A girl smiled and unceremoniously took Macon from my wife’s arms. The mob raced about the lobby showing their prize to everyone they knew, disappeared into the kitchen for a couple of minutes, and came back, delighted, and put Macon, uncooked, back where they had found her.

I have a hard time getting from there to weaselly, sinister, and devious.

We went to Gwo Yu R Bau to say hello to Jang Lao Shr, who was still there, and to the bridge to see Shwei Gwo Syau Jye, who also was still there. Still reading Newsweek, still working long, long hours. It was delightful. I never saw her again.