The Great British Betrayal, by Keith Woods

Since the election of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1979, Britain has undergone a great experiment. Economically, the UK became the exemplar of neoliberalism in Europe. Politically, the UK has quietly transitioned to a postnational state, undergoing one of the greatest demographic transformations in the West.

Although the landslide victory of Tony Blair’s “New Labour” in 1997 may have seemed like a return to the model of European social democracy that Britain exemplified after the Second World War, Blair’s “Third Way” represented rather the embrace of neoliberalism by the establishment Left, summed up nicely by their spokesman Peter Mandelson’s declaration that “we are all Thatcherites now”.

Under the leadership of both the Conservative Party and New Labour, Britain has transitioned from a traditional industrial and manufacturing powerhouse to a highly financialised rentier economy. The effects have been profound. The average Briton is considerably worse off and entire regions have been left behind at the same time London has become a booming centre of international finance. The UK has been denationalised by decades of mass-immigration and cultural leftism, and has become the prime example of “anarcho-tyranny”, where the state punishes minor offences and acts of dissent against the liberal consensus with extreme force, while serious crime runs out of control in major cities.

The Rentier Regime

The fundamental transformation in the British economy since the 1980s is the movement away from an economy that made things to an economy that made money . Up to then, Britain’s economic might had been centered on its manufacturing. Britain was the birthplace of the industrial revolution, and the dual expansion of its colonial empire and rapid advances in engineering allowed for the creation of a vast trading network, where colonies provided the raw materials and markets for British manufacturing. Northern English cities like Manchester, Sheffield and Newcastle became manufacturing powerhouses serving the world.

Britain has shifted from an entrepreneurial capitalism to rentier capitalism: an economic system organised around income-generating assets. In this system, ownership of sought-after scarce assets — land, natural resources, intellectual property — is the source of a significant portion of economic activity, and the regime is dominated by vastly wealthy rentiers. Wealth is built around having rather than doing.

In his book Rentier Capitalism, the economic geographer Brett Christophers showed that the main effects of Thatcherite-era reforms were to open up new income streams to rentiers that had little or no productive effects. The pattern since then has been the privileging of rentier accumulation over investment in productive economic activity. The share of UK GDP coming from manufacturing was 32% in 1973, today it is under 9%. The UK today is producing a lot of money, but not much else.

A number of developments have empowered rentiers and disempowered renters since the first Thatcher government: following the monetarist prescriptions of the Chicago school of economics, Thatcher’s government privatised vast quantities of public assets and deregulated financial markets, which allowed for a massive growth in interest-bearing credit (household debt increased from 37% to 70% of GDP under Thatcher). The big discoveries of oil and gas in Britain’s North Sea, as well as the emergence of new rent-generating digital technologies and platforms has also led to the swelling of rentier portfolios.

Successive governments have amended tax policy to favour rentiers. For example, in 2016 the Conservative government introduced “The Patent Box”, which allowed companies to pay a substantially lower corporate tax of just 10% on profits earned from intellectual property. This has mostly benefited corporate giants like GlaxoSmithKline, the UK pharmaceutical company who reported that this change led to them keeping an extra £458 million per year.

The UK was also the first government to pioneer Public Private Partnerships, under which public services and infrastructure are outsourced to private companies to collect rents, though much of the financial risk remains with the state. These PPP schemes have not only led to huge windfalls for the private companies operating them, but have been shown time and again to cost the government more than if it funded public projects directly. A report on “The UK’s PPPs Disaster” notes that:

Since 1992 PPPs yielded public assets with a capital value of $71 billion. The UK government will pay more than five times that amount under the terms of the PPPs used to create them.

Not only this, but much of this giant rent extraction from the British public to private finance is offshored and avoids taxation. In 2011, the UK Public Accounts Committee reported that investors were extracting huge profits from British taxpayers by buying up contracts for schools and hospitals funded through PPPs, and taking the proceeds offshore. The committee reported that many PPP contractors are based in offshore tax havens, making a mockery of the assumption held by the UK Treasury that these contractors would benefit the British economy by paying tax.

The Thatcher government also gave enormously generous terms for the oil companies which extracted British North Sea oil. The discovery of abundant oil and gas reserves in the North Sea can take a lot of credit for funding the economic boom in the 1980s, helping to mask the contraction that was happening in the real economy in this period.

But while countries like Norway invested large oil discoveries into long-term investments like sovereign wealth funds, Thatcher’s government used it to fund cuts in the higher rates of income tax. One economist estimated that had the 3% of national income that was being generated from oil and gas extraction been invested in ultra-safe assets, it would conservatively have been valued £450bn by 2008. Instead, this money was used to fund a great cash giveaway for the highest earners in British society, much of which was then invested back into property assets and used to inflate the housing market, rather than stimulate real economic growth.

Privatisation, deregulation and financialisation has led to Britain becoming, in the words of the Financial Times, a “rentier’s paradise”. All the while, this transformation and the huge wealth transfer it brought has been subsidised by the British public, most of whom have seen declining or stagnant living standards for decades. The UK is a rentier regime — all policy since the 1980s can be understood as favouring rentiers, even (and often) at the expense of the national interest.

London’s financial black hole

London had historically been the seat of British finance and government, but under Thatcher, the financialised economy began to increasingly decouple from the traditional economy while becoming the driving force behind the new model’s economic growth. The highest levels of the UK government and the Bank of England came to increasingly serve the interests of the London financial elite. The new model adopted in Britain was:

Very much influenced by people with financial market backgrounds. They knew a lot about the City and capital markets but relatively little about manufacturing and regional industries. Markets to them were all about transactions, not production, labour or materials. Industry was part of an ageing foreign space for them. Finance was their new world.

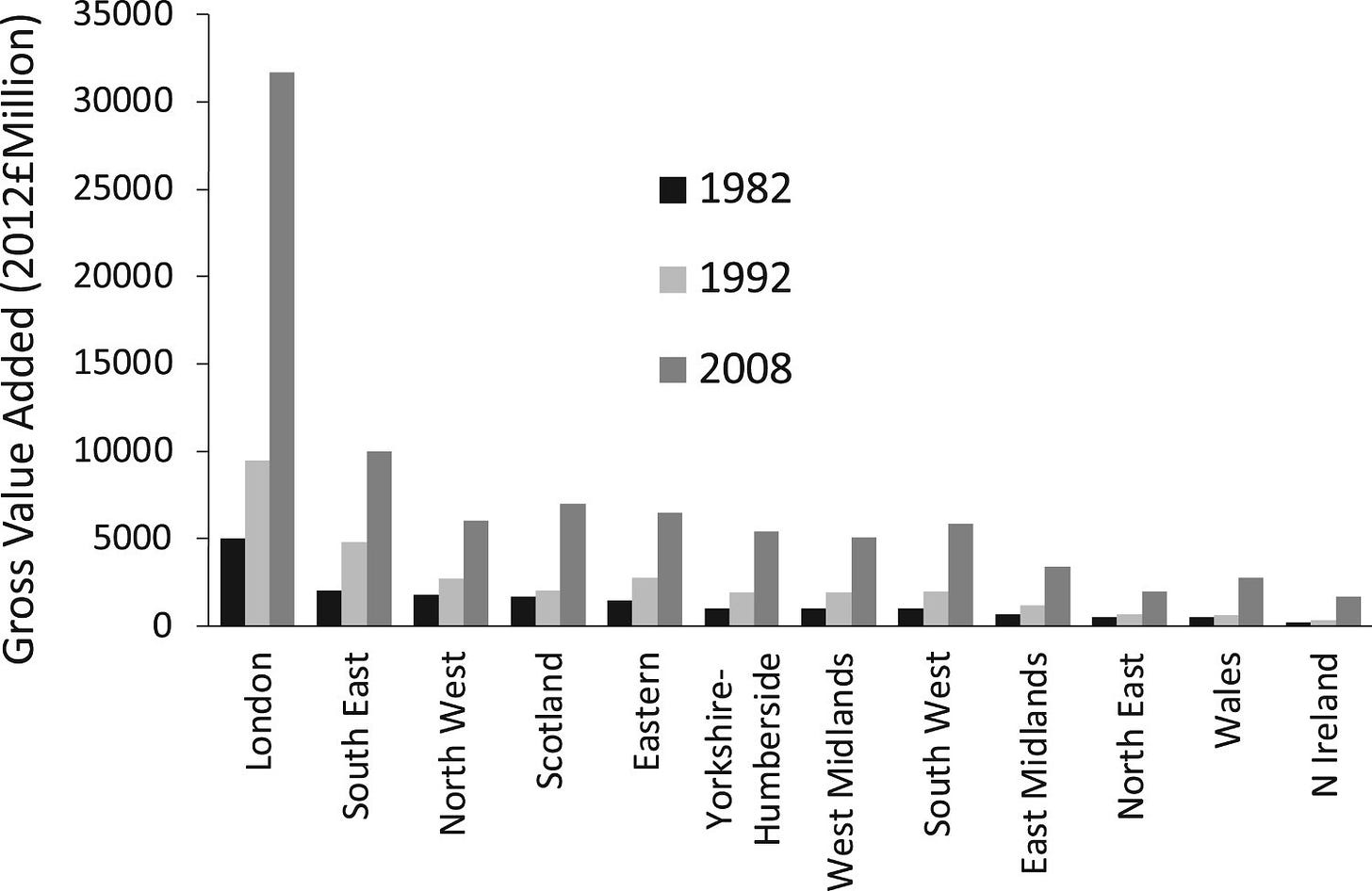

The graph below demonstrates the explosion in London-based financial services in delivering growth for the British economy

As well as allowing the growth of financial services in London, the deregulation of successive Thatcherite-Blairite governments has made London an enormous centre of speculation. Property in London has become an especially popular commodity for the world’s elites to speculate on. In 2015, it was reported that non-resident buyers had spent over £100 billion on UK property in the previous six years. Foreign buyers now account for 41% of activity on the London property market. Many of the high end residential properties snapped up by oligarchs are left empty — London now has over 34,000 homes classified as “long-term vacant”.

Hearing that London is both a booming financial centre and the top destination for the world’s super rich, anyone would be forgiven for assuming that this is an unmitigated good for the UK’s economy. But there is good evidence that the London financial centre has become a black hole on the rest of Britain and its more traditional economy.

It was conventional wisdom of the neoliberal reformers that a growth in the financial sector would benefit other sectors of the economy: not only is there more money fluctuating in search of investment opportunities, but a larger finance sector means more knowledge circulating about the markets it studies, more efficient markets, and thus more effective investments.

Since the 2008 financial crash, much has been learned that challenges this assumption. A 2015 study by the Bank of International Settlements concluded that:

The growth of a country’s financial system is a drag on productivity growth. That is, higher growth in the financial sector reduces real growth. In other words, financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing, likely because the financial sector competes with the rest of the economy for resources.

Referring specifically to Britain, the authors of The Finance Curse write that:

‘Financialisation’ has crowded out manufacturing and non-financial services, leeched government of skilled staff, entrenched regional disparities, fostered large-scale financial rent-seeking, heightened economic dependence, increased inequality, helped disenfranchise the majority and exposed the economy to violent crises. Britain is subject to ‘country capture’ with the economy constrained by finance, and the polity and media under its influence.

In 2018, a trio of economists tried to put a number on the cost of this ‘finance curse’. They concluded that in just a 20 year period, from 1995 to 2015, excessive financialisation cost the UK economy £4.5 trillion in unrealised growth.

Deregulation has also allowed the UK to become a global centre for financial fraud. A 2016 report estimated that financial fraud costs the UK £193bn per year — more than the entire budget of the National Health Service. Margaret Hodge, the former head of the UK’s Public Accounts Committee, named Britain as “the country of choice for every kleptocrat, crook and despot in the world”. In one high profile case that demonstrated this role London now serves, the city was at the centre of a massive Russian money-laundering scheme where Russian insiders laundered as much as $80 billion in dirty money, passing it through fictitious companies registered in London.

The City of London — the deregulated, semi-independent financial district of London — is also at the centre of the world’s “shadow banking” economy, which is now estimated to account for half the world’s assets. Britain has created, since the 1950s, a deeply complex financial ecosystem which makes use of deregulated offshore British jurisdictions like the Cayman Islands and Jersey, allowing the world’s super rich to hide their wealth and business activities from tax and regulation.

Deregulation by the British government of the “Eurodollar market” of offshore trading — done consciously at a time of British colonial decline to try and maintain British financial power — allowed the City of London to become “the main nerve centre of the darker global offshore system that hides and guards the world’s stolen wealth.” The City of London thus benefits from depriving the world of hundreds of billions in lost taxation and facilitating fraud and deceit on a massive scale.

An overlooked way in which financialisation drags down the rest of the economy is in how the rentier state treats the national currency. The attempt to make Britain a hub for inflows of foreign money has made successive governments want a “strong” or overvalued pound sterling relative to other currencies.

The effect of this overvalued pound contributed substantially to the decline of British manufacturing — exporters suffer from an overvalued currency, as their products become less affordable to other countries. From 1950 to 1970, Britain’s share of the world’s manufacturing fell from 25% to 10%. While this has often been presented as an inevitable feature of modernisation, in the same period Germany grew its share from 7% to 20%. The key difference is that in Germany, monetary policies have consciously been set to favour the growth of industry, whereas Britain has treated industrial interests as subordinate to finance and banking.

In leaning on finance to replace the economic growth once provided by industrial output and innovation, Britain followed the course of other once great empires. Previous capitalist hegemons like Genoa and the Netherlands also encouraged financial speculation and tried to build their economies on usury as they went into decline.

For Britain, this has allowed the country to maintain a level of economic might that its citizens were accustomed to, but this is a precarious state of affairs. The economist Philip Pilkington explains how this affair with international finance works:

Britain is allowed to run large trade deficits because its trade partners are keen to hold British-domiciled financial assets. This in turn allows Britons to live beyond their means. Foreigners send Britain goods they would otherwise be unable to afford, Britain sends sterling in return and instead of dumping sterling onto foreign exchange markets — thereby driving down its value and rendering the goods less affordable for Britons — the foreigners buy British financial assets. Britain is a potentially rather low-income country living the life of a high-income country, and the whole show is kept on the road by the financiers in the City. A clever arrangement — but clearly an unstable one.

There is already reason to think this precarious relationship is in jeopardy. The rich are fleeing the UK in droves — 9,500 millionaires are set to leave the UK in 2024. The UK is only behind China worldwide for millionaire emigration, but outpaces it per capita by a factor of 14.

At the same time, many heavy hitters within the British economy are being sold to American capital. Blackrock has just finalised a deal to acquire the UK-based data provider Preqin for $3.2 billion. To economists like Pilkington, this is another phase in Britain’s long decline and retreat from the world stage, the final consolidation of a post-war settlement which made the UK a subordinate partner to the United States:

In the Eighties and Nineties, Britain managed to carve out a place in the world by becoming a major financial centre. But it has long been well-known that the City of London is just an outpost of Wall Street. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the City has waned in importance with more and more British companies being listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Now the financialised British economy is being actively weaponised against the country to asset-strip its companies and place them under American ownership.

Left Behind

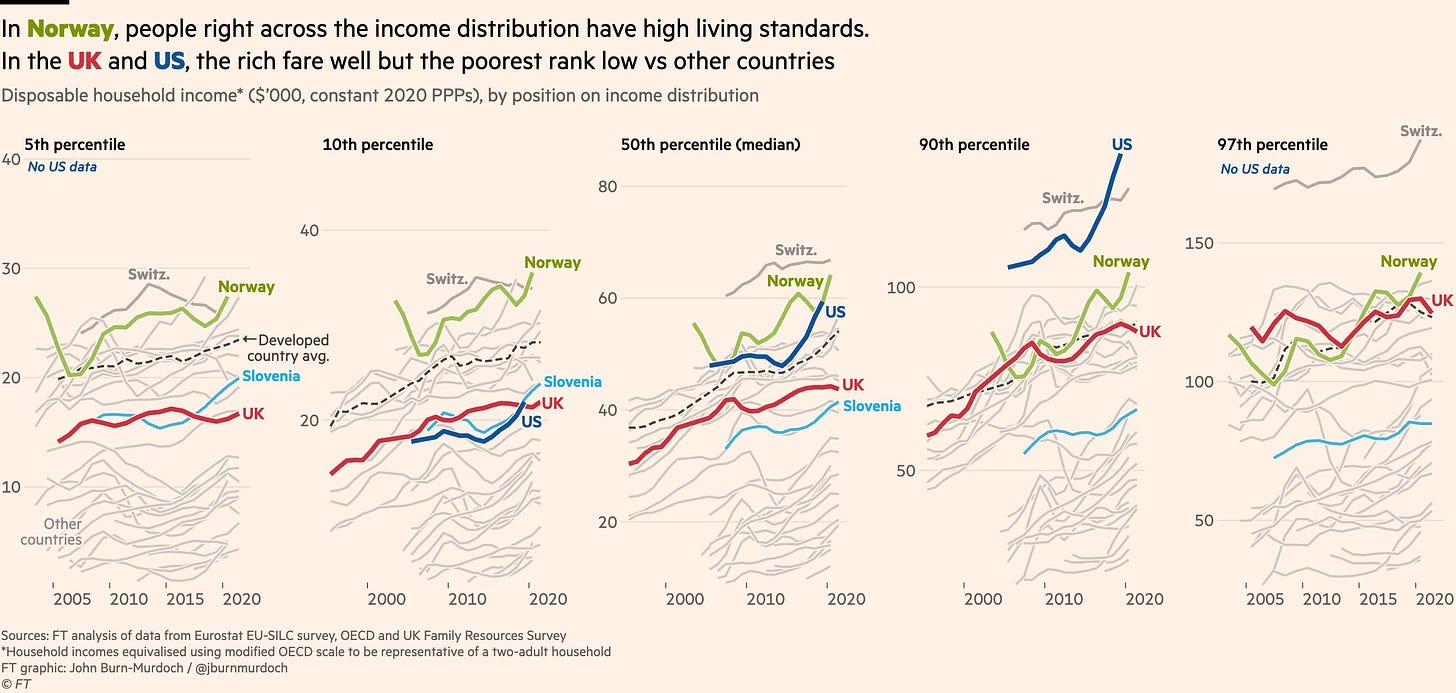

A 2022 piece in the Financial Times painted a bleak picture of the economic reality for most Brits that is masked by popular measures of economic health like GDP. Although Britain has many wealthy people, the average person is not very well off compared to other developed countries. In fact, the lowest-earning bracket of households in Britain were 20% worse off than their counterparts in Slovenia. The British middle class is also rapidly declining in its living standard relative to the rest of Europe:

In 2007, the average UK household was 8 per cent worse off than its peers in north-western Europe, but the deficit has since ballooned to a record 20 per cent. On present trends, the average Slovenian household will be better off than its British counterpart by 2024, and the average Polish family will move ahead before the end of the decade.

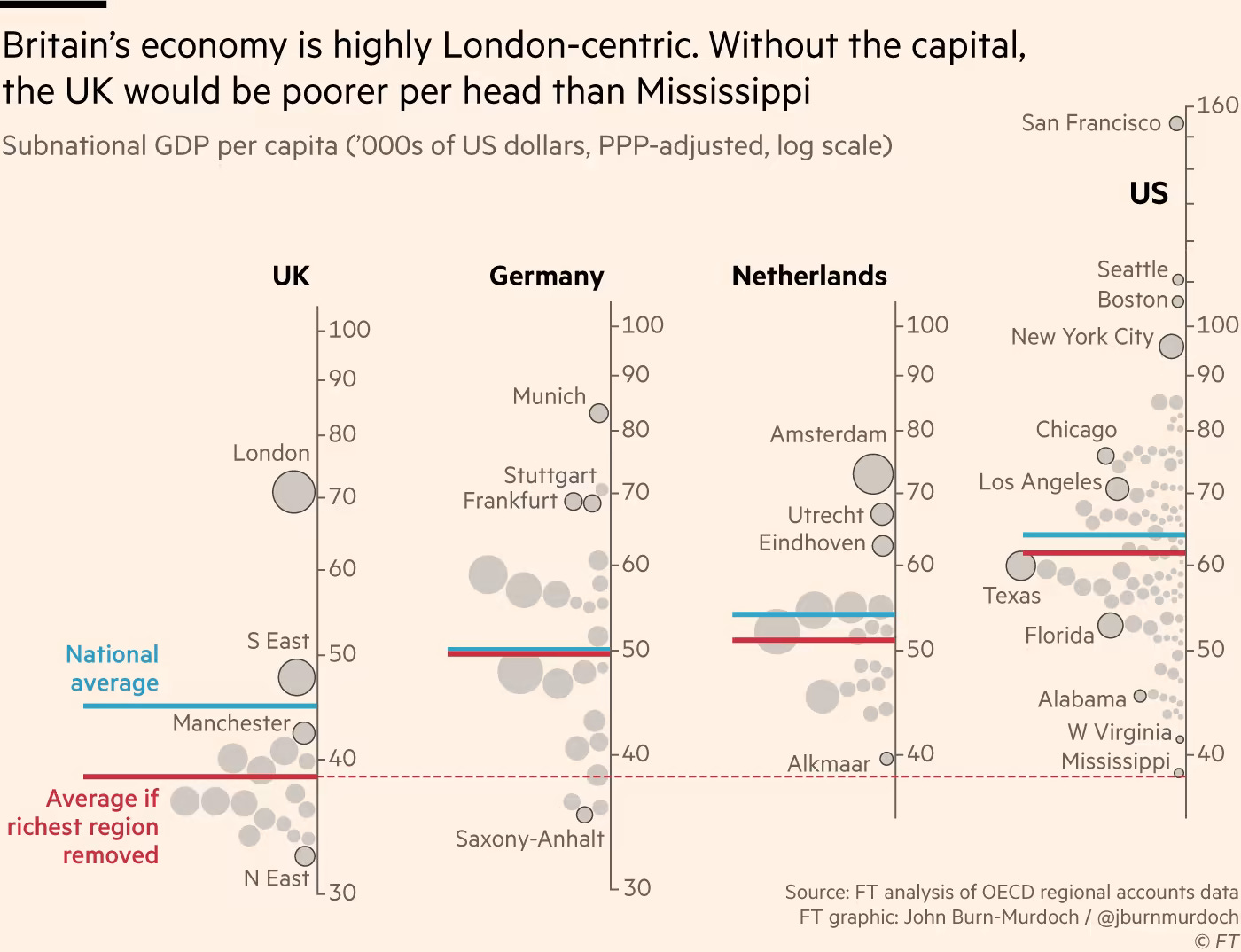

Britain is, in the authors words, a poor country with some very rich people. Another way to put it might be that Britain is poor country with one very rich region. Data presented by the same author shows that removing London would take 14% off average British living standards, enough to leave the remainder of Britain poorer than every state in the US.

This reflects how much Britain’s general decline has been masked by the growth of finance capitalism. The British economy has been stagnant since the 2008 financial crisis. In the period since, real wages have declined by 3%. For comparison, real wages in Germany grew by almost 9% in the same period. This has been coupled with a cost of living crisis and persistently high inflation since 2021, as well as a rising cost in rents. More than a third of people in Britain spend over half their income on rent, 80% spent over a third. Here too, the shift to a rentier economy has been devastating.

In the general election that won her power in 1979, one of Margaret Thatcher’s more popular promises was the “right to buy”, promising over 5 million tenants of social housing the right to buy their home from the local authorities at much reduced rates. The average discount obtained by those availing of the scheme was 44%, an amazing bargain considering how much the value of many of these houses would inflate since — in southern England in 1981 the average valuation of a Right to Buy property was just under £20,000. Most sales were financed by lending.

This policy embodied Thatcher’s ethos as much as any, flogging off public resources at a discount, funded by private credit, and instilling in the millions of new homeowners a spirit of risk-taking individualism and independence from the welfare state.

In the following decade, rents rose substantially on those who did not avail of the Right to Buy. In effect, poorer renters subsidised through higher rents the ability of their wealthier neighbours to become homeowners. Since Right to Buy, the number of social housing available has plummeted, as has building of these houses. 40% of ex-council flats sold through statutory Right to Buy are now private rental properties. So, while lower-middle class Britons got to experience affordable home ownership in the 1980s, millions of younger people now exist in precarity around housing, forced into overly expensive privately rented accommodation with no hope of affording a home.

The scheme also took away power from local authorities, who can now do little about local housing problems other than turn to the London government. This was one of the largest privatisation schemes ever undertaken, a major step in the transition to a rentier economy, and a classic example of politicians cashing in on short term gain at the expense of long-term concerns. Much like the cash giveaway taken from North Sea oil, Thatcher’s government took from future generations for short term abundance.

Of course, no housing crisis can be explained just by looking at supply, and housing is one of the sectors of the economy most clearly affected by decades of mass-immigration.

The Migration State

I have previously written on Britain’s demographic transformation through mass-immigration. I won’t restate the analysis presented there, but in this context it is worth discussing how Britain’s transformation into a migration state went hand in hand with its embrace of neoliberalism.

The left in Britain, as in the rest of Europe, has been keen to present a narrative of Britain as a historically multicultural country. At the same time, the Dissident Right , in its focus on the radical changes affecting Europe after the Second World War sometimes miss just how recent the radical demographic changes of European nations are. The 1980’s …

Net-immigration to the UK exploded under the New Labour government after 1997, and continued with successive Conservative governments since the 2010s, now at a historic high. This was largely ideologically driven, as former Labour advisor Andrew Neather admitted his party wanted to rub the right’s nose in diversity, and “make the UK truly multicultural.”

But New Labour’s embrace of neoliberal economic prescriptions also drove this new approach to immigration, as Labour shifted from its traditional Keynesian economic approach to prioritise labour market flexibility and counter-inflation. Labour representatives spoke of the mass-migration of people as a necessary part of living in a global, financialised economy, comparing it to the free movement of capital. A special advisor to the party reflected on the change in immigration policy as coming from

the reorientation on economic policy of the centre left—away from Keynesian demand management towards a more explicit embrace of globalisation—lent itself more firmly towards embracing immigration too. The emphasis on skills and education and openness to global markets meant that you had people more open to arguments about migration being an important component of a successful economy.

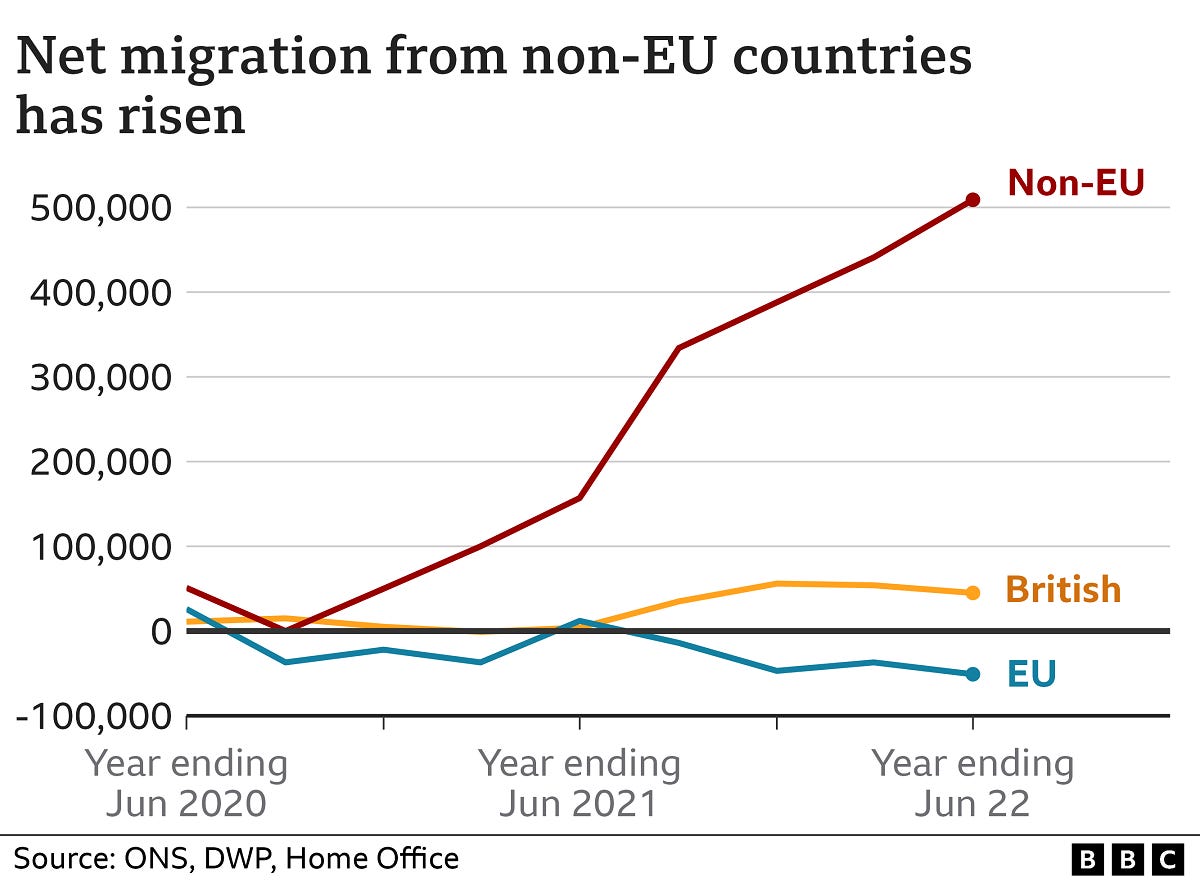

What began as New Labour policy has become cross-party consensus in Britain. Net migration was 685,000 in 2022. While a major motivation for many who voted to leave the European Union was an opposition to mass-immigration, the Tories have responded by increasing immigration. In fact, the main result of Brexit on immigration has been to simply swap EU migrants with even more culturally incompatible non-EU migrants.

It seems that, after decades of betrayal, voters concerned about immigration are at last willing to abandon the Conservative Party in droves. Though at this point, the change to British demographics has been enormous. The 2021 census of England and Wales showed that 10 million people, or one-sixth of the population, were born outside the United Kingdom.

In 2010, the demographer David Coleman produced an analysis which forecast White Britons becoming a minority by 2066. Since immigration has expanded greatly since then, this figure can likely be revised forward. Minority status is already a daily reality for many White Britons, who are now a minority in major cities like Manchester, Birmingham, Leicester, and London — where two thirds of the capital’s residents are ethnic minorities.

Anarcho-Tyranny

Another defining feature of the postnational British state is anarcho-tyranny, the increasing breakdown of the state’s capability to maintain law and order and its failure to prosecute the most basic crimes, combined with the increasingly tyrannical policing of civil society and suppression of liberties once taken for granted.

British police are now more incompetent than they have ever been: an investigation into their ability to investigate crime found that more than half the forces studied failed to meet basic standards. Not one of the 43 constabularies studied made the top category of “outstanding”. Most Britons no longer expect the police to investigate crimes like mugging or bike theft, and many no longer bother reporting these types of crimes. This is a correct assumption: between 2015 and 2023 in England and Wales the percentage of crime resulting in the offender being caught by the police and taken to court fell from 16% to 5.7%. Police now solve fewer than 3% of burglaries. Most criminals have little chance of ever facing punishment in the UK.

In contrast, the state has proven absolutely committed to policing the speech of White Britons, especially if it concerns criticism of multiracial liberal pluralism. A 2017 article in The Telegraph reported that more than 3,300 people were detained and questioned in the previous year over “trolling” on social media and other online forums. Two particularly egregious examples of this kind of policing came in 2018: first, a 19-year-old woman was convicted of sending a “grossly offensive” message after she posted rap lyrics that included the N-word on her Instagram page. Then, the YouTuber Count Dankula was found guilty of a hate crime for posting a video that showed his pug raising its paw in what he called a Nazi salute.

British police also track “non-crime hate incidents”, encouraging the public to report if they take offence to someone’s speech on the basis of their “protected characteristics”. The police are instructed that in the case of these reports “the victim does not have to justify or provide evidence of their belief, and police officers and staff should not directly challenge this perception.” Almost 120,000 of these incidents were recorded in the 5 year period from 2014 to 2019.

The greatest tyranny has been reserved for nationalists. This year, Sam Melia, an activist and organiser with Patriotic Alternative, was sentenced to two years in prison for “inciting racial hatred”. Melia had set up a group called the Hundred Handers on Telegram, which posted graphics intended for members to download and print as stickers. The stickers contained messages like “its OK to be white”, “love your nation” and “stop anti-white rape gangs”.

The prosecution used materials found in a search of Melia’s house, such as a book by Oswald Mosley, as “key signs of Melia’s ideology that underpinned his desire to spread his racist views in a deliberate manner.” Thus, Melia’s private reading material was used as evidence that he harboured views the prosecution considered racist.

At the trial itself, the prosecution acknowledged the language on the stickers were lawful, but were produced as a body of work intended to stir up racial hatred. The jury was also instructed to ignore any consideration of whether the statements on the stickers were actually true, as truth is no defence in cases such as this. The jury duly found Melia guilty, after which he was sentenced to two years in prison.

The ideological commitments of the stewards of the British state have not only led them to targeting political dissidents, but also to covering up crime on a massive scale. We now know that British police and state institutions ignored and helped conceal the greatest child sexual abuse scandal in British history, with a series of pedophile “grooming gangs” composed of Asian, mostly Pakistani men ignored for years.

A report into the worst of these, in the town of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, found that 1,400 children had been sexually abused from 1997 to 2013, predominantly by men of Pakistani origin. It revealed that council staff and others knew of the abuse but turned a blind eye to what was happening and refused to identify the perpetrators due to their fear of being branded as racist.

The same conclusion was reached after an 8 year investigation by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, which found that grooming gangs still existed across the country, but investigations into them were still being hampered by authorities’ fears of pursuing so many non-white criminals.

The End?

I am publishing this on July 4 2024, the day of a UK general election. By the time you read this, it is likely the Conservative Party will have suffered its worst electoral defeat ever, handing a landslide majority to the Labour party. Decades of betrayal of their patriotic voter base has brought them to a point of absolute fatigue. The Thatcher-Blair-Cameron neoliberal consensus which has governed Britain for almost half a century now has transitioned the country from a proud and cohesive nation into a postnational economic zone, increasingly subservient to American finance capital and in a state of terminal decline.

The prospects of reversing these trends is bleak, especially if political power shifts to a political Left equally committed to diversity and the repression of patriotic sentiment. But leaving the Conservative party in the dustbin of history may be a start to what remains of the English, Scottish and Welsh nations reasserting themselves.

Notes

Davis, Aeron. Bankruptcy, bubbles and bailouts: The inside history of the Treasury since 1976. Manchester University Press, 2022. Pg. 82-83.

Cecchetti, Stephen G., and Enisse Kharroubi. “Why does credit growth crowd out real economic growth?.” The Manchester School 87 (2019): 1-28.

Christensen, John, Nick Shaxson, and Duncan Wigan. “The finance curse: Britain and the world economy.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18, no. 1 (2016): 255-269.

Baker, Andrew, Gerald Epstein, and Juan Montecino. “The UK’s finance curse? Costs and processes.” SPERI report (2018).

Eglene, Ophelia. Banking on Sterling: Britain’s Independence from the Euro Zone. Lexington Books, 2011.

Quoted in Consterdine, Erica. Labour’s immigration policy: the making of the migration state. Springer, 2017. Pg. 130