Protestantism, Jews and Wokeness, by Keith Woods

Steve Sailer recently wrote an essay titled In This House We Believe: The Protestant Roots of Wokeness. Sailer states that his intent is to argue against what he calls the “obsession among callow rightists about declaring wokeness a foreign, un-American import by Marxists or Jews or Jewish Marxists or whatever.” With all the talk about “wokeism” on the right lately, it is something that warrants a serious attempt at providing an intellectual tracing of its roots, but I found this essay lacking in Sailer’s characteristically rigorous analysis.

Sailer is not the only intellectual to look to explain wokeness as an expression of Christianity or a Christian heresy. Popular blogger Noah Smith described wokeness as “a combination of abolitionism and Protestant Christianity”, arguing that the abolitionist movement of the 18th and 19th centuries, started by zealous Christian activists, was the original woke movement.

In Sailer’s case, he is inspired by a more recent essay written by a religious sociologist named Sheluyang Peng, who argued wokeness is an expression of Northern US Protestant religious values. Sailer quotes the following argument from Peng’s More Christian than the Christians:

Wokeness appears to be a syncretic blend of Puritanism and Quakerism. Woke adherents value elite education and moralizing, seem obsessed with rooting out heretics, adhere to orthodoxy, and display a sense of personal salvation, traits that were all characteristic of Puritans, while also displaying the radical openness and commitment to egalitarianism that characterized the Quakers.

I am skeptical of explanations like this, which argue secular political orthodoxies are the exact same character as religion, or try to trace a direct genealogy from the behaviour of young, barely informed political radicals back to their pious ancestors. Some “anti-woke” intellectuals have taken this kind of genealogical thinking so far they have tried to trace the origin of wokeness back to Gnosticism and 2nd century intra-Christian disputes.

This might be a fun intellectual exercise, but I think it’s a stretch to take religious attitudes and dogma, find similarities in secular political movements, and treat this as proof of some kind of causation. How could we test Peng’s theory? If Protestant attitudes were really at the root of wokeness, shouldn’t we expect their attitudes and voting patterns to have telegraphed this transformation? But of course, Protestant Christians have consistently shown the most conservative attitudes on everything from desegregation to gay marriage.

Still, it is true that something like wokeism would be inconceivable without the background assumption of universal human dignity we’ve inherited from Christianity. I agree with Nathan Cofnas’ basic equation of wokeism as “simply what follows from taking the equality thesis of race and sex differences seriously, given a background of Christian morality.” — Neither Christian moral precepts or a belief in racial egalitarianism is enough to make one woke, but combine both, and its easy to see how a frenetic search for the roots of inequality in institutionalised racism, white fragility or microaggressions follows.

If this modest thesis was all being put forward by Sailer, I wouldn’t be writing this. But Sailer’s piece is intended as a refutation of the idea that Jews significantly shaped the character of American liberalism and wokeness. A Christian moral inheritance and a certainty in blank-slatism are necessary, but not sufficient conditions to explain the transmutation of liberalism into wokeness, but that glosses over about a century of academic and political wrangling and leaves the reader with the sense that these all followed like clockwork from the religious inheritance of the United States. I think examining the origin of these political currents shows otherwise, and this is where the aspect of Jewish influence is a story that needs to be told.

Sailer dismisses the claim of a significant Jewish influence with two arguments. First, he does a demographic breakdown of The Atlantic Monthly’s December 2006 feature on The 100 Most Influential Americans. Sailer notes that many of the white, Protestant men on this list — Lincoln, FDR, Teddy Roosevelt etc. — were left wing by the standards of their time, showing a trend of homegrown figures continually advancing the progressive logic of the American project through every epoch, absent any subversive outside influence. He also notes that the list contains only seven Jews:

That’s a healthy number, but it might be fewer than you’d expect from 21st-century discourse. For example, Emma Lazarus of the “huddled masses” poem is now often depicted as a founding father whose word is law on immigration. But she didn’t make the list.

In general, Jews didn’t get here quite in time to be extremely influential on the long course of American history. This fact tends to annoy both Jews and anti-Semites, both of whom want to overstate Jewish influence.

I don’t think this is a very useful exercise for evaluating the influence of Jews on political orthodoxy. Firstly, this encompasses all of American history, and anyone arguing for strong Jewish influence would acknowledge this only really came to the fore in the 20th Century, and especially after the Second World War. Sailer responds that this is too short a time period for Jews to have exerted much influence on things, but this is obviously less true for the claim that they had a strong influence on wokeism, which is a relatively recent phenomenon in the long course of American history.

And when we talk about wokeism, it’s obviously the 20th Century that really matters. At the beginning of the 20th Century, American Christians still took for granted things like natural race differences, segregation, and restrictions on pornography. Progressives of the time championed Darwinism and eugenics. It was later in the 20th Century, with the rise of Boasian anthropology, and especially the rise of a new, Jewish-dominated elite in the 1960s in critical areas of American life like the social sciences and the media, that the character of progressivism changed to adopt the characteristics of wokeism today: blank-slatism, anti-white enmity, pluralism, relativism, sexual liberation etc.

Many of the figures on the list used by Sailer are presidents, generals, inventors and scientists. If we were to draw up the 100 most influential figures to shape American political thought, few of these would feature. John Rawls does not feature on The Atlantic’s list, but he is arguably the most influential American philosopher of the 20th Century, with his Theory of Justice ranking as one of the most cited books in the social sciences, and his arguments cited in dozens of court cases. Rawls is certainly more relevant to a discussion of the evolution of American progressivism than Thomas Edison or Robert E. Lee, two names found on the list.

It would be difficult to find any agreement on a list of the 100 figures most responsible for the intellectual currents that shaped wokeism, but we can imagine a few names that would have to feature for the list to be authoritative: we could include multiple members of the Jewish Frankfurt school — Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse — who birthed critical theory and its many offshoots; Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies did as much as any book to shape the character of post-war liberalism, with its emphasis on pluralism and minoritarianism, and surely warrants him a spot; Gayle Rubin would have to feature as the founder of Queer Theory, as would Leslie Feinberg, one of the first leftists to promote the idea of “transgender liberation” to a significant audience; Judith Butler is credited with being the first to popularise the “gender is a social construct” idea’; while Franz Boas, Ashely Montagu and Claude Lévi-Strauss deserve a large share of credit for popularising the ideas of racial egalitarianism the left take for granted today.

Just with some of the heavy-hitters of 20th Century leftism, we’re already at 10, so I’m confident the final draft would tell quite a different story to the one Sailer is drawing on.

The turn away from assimilation

Sailer also quotes Peng to make the case that Jewish left-wing influence in academia was actually a reflection of them assimilating into the dominant, Protestant-progressive culture that already existed in their new home, rather than a subversion of that tradition:

Whereas anti-Semites today like to blame Jews in academia for “cultural Marxism,” the correlation actually runs the other way: Jews gave up their faith and assimilated into liberal Christian values, including sometimes literally converting to Christianity.

It’s not clear which Jews Peng is talking about here. If it’s the Frankfurt School theorists who pioneered what became known as “cultural Marxism”, they certainly never embraced or assimilated into American Christian culture. These theorists remained obsessed with the dangers of “thinking with the blood.” They remained hostile to the US liberal economic system and the injustices of the free market as ripe for producing mass discontent which could veer into antisemitism.

Sometimes, members of the Frankfurt school advocated universal, cosmopolitan values while warmly re-embracing their own Jewish ethnic identity. One example is an article written in the Jewish Commentary magazine by Frankfurt School member Leo Lowenthal in 1947. Lowenthal wrote on fellow Jew Heinrich Heine, who converted to and later renounced Christianity. Lowenthal:

Unearthed an urge that resonated for both himself and for the entire world of the New York Intellectuals…Heine, like Germany’s Jews and the young New York writers, abandoned the parochialism that he perceived in traditional Judaism and sought to fashion a new identity founded in universal reason.

However, both Heine and Lowenthal, and the other Frankfurters and New York Intellectuals who explored this in the pages of Commentary, eventually abandoned this ideal of a universal community and embraced Jewish chauvinism. Lowenthal quoted approvingly the words of Heine, who concluded:

My preference for Greece has since declined. I see now that the Greeks were merely handsome youths, while the Jews were, and still are, grown men, mighty, indomitable men, despite eighteen centuries of persecution and misery. I have learned to rate them at their true value.

Thus, Lowenthal “acknowledged that Judaism was a tradition that need not be transcended in the name of loftier ideals.” Lowenthal and the New York intellectuals were able to find a way to embrace their particularist Jewish identity — even Jewish supremacy — and marry this to the “Critical Theory and the prewar political impulses that gathered the Horkheimer Circle together.” Far from embracing assimilation, none saw a contradiction in taking an adversarial stance to the host traditions and ethnic self-conception of America while embracing their own ethnoreligious identity.

A similar observation was made by Jewish political scientist Charles Liebman about the attitude of Jewish émigrés to America. Liebman wrote that:

The Jew desperately sought to participate in the society and rejected sectarianism as a survival strategy, yet at the same time refused to make his own Jewishness irrelevant…The Jewish political quest was for an ethic which could be posed against society’s traditions. To this extent then, the Jew sought to Judaize society.

Elliott Abrams writes that the organised Jewish community in America:

Clings to what is at bottom a dark vision of America, as a land permeated with anti-Semitism and always on the verge of anti-Semitic outbursts.

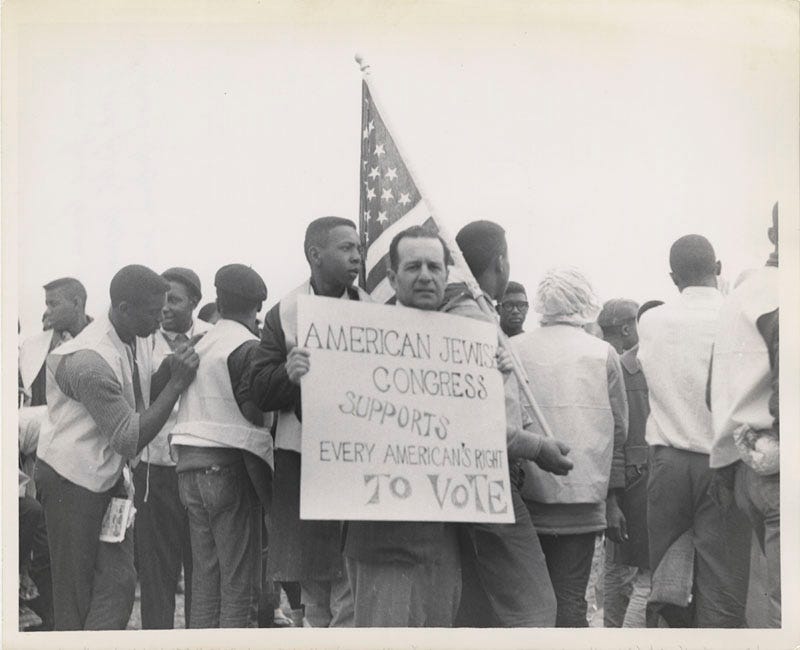

According to Abrams — a former National Security Advisor — this perspective motivated Jews to take a leading role in secularizing America. Jewish groups like ADL and American Jewish Congress used the legal system to advance secularisation and a greater separation of church and state. Especially after World War 2, and the dawning of a “Jewish Golden Age”, Jewish bodies moved from an embrace of religious liberty and collaboration with the dominant WASP culture to a more aggressive assertion of perceived Jewish interests.

Setting the tone for this thrust, in 1945, the American Jewish Congress published a credo calling for an “active alliance with all progressive and minority groups engaged in the building of a better America”, arguing that the fate of Jews was now “indissolubly bound to those of the forces of liberalism.”

Another Jewish historian, Murray Friedman, documents how this move to a more aggressive push for liberalism motivated the leadership of early Jewish civic bodies, desiring to reshape American Christian culture to empower minorities and eliminate discrimination:

Having grown up poor in Eastern Europe or in families of recent immigrants, they identified strongly with victims of poverty and other forms of social displacement. They were drawn to left-wing formulas, especially stressing the role that government could play in bringing about greater justice. They believed strongly that the battle against anti-Semitism had not ended with the demise of Hitler but rather persisted in discrimination against Jews at management levels in industry and finance, in housing, in education, and at leisure resorts. Central to their belief was the idea that Jews could never feel safe unless prejudice and discrimination against all minorities were wiped out.

Crucially for the argument put forward by Peng and Sailer of this being a continuation of the Christian underpinnings of American society, Friedman contends that this more assertive stance was actually a conscious challenge to the established liberal view of religion in America:

At heart here was a clash of cultures – the secular and ascendant cosmopolitan culture, in which Jews were now so heavily invested, and the older Christian and Tocquevillian tradition that religion is essential for a healthy civil society.

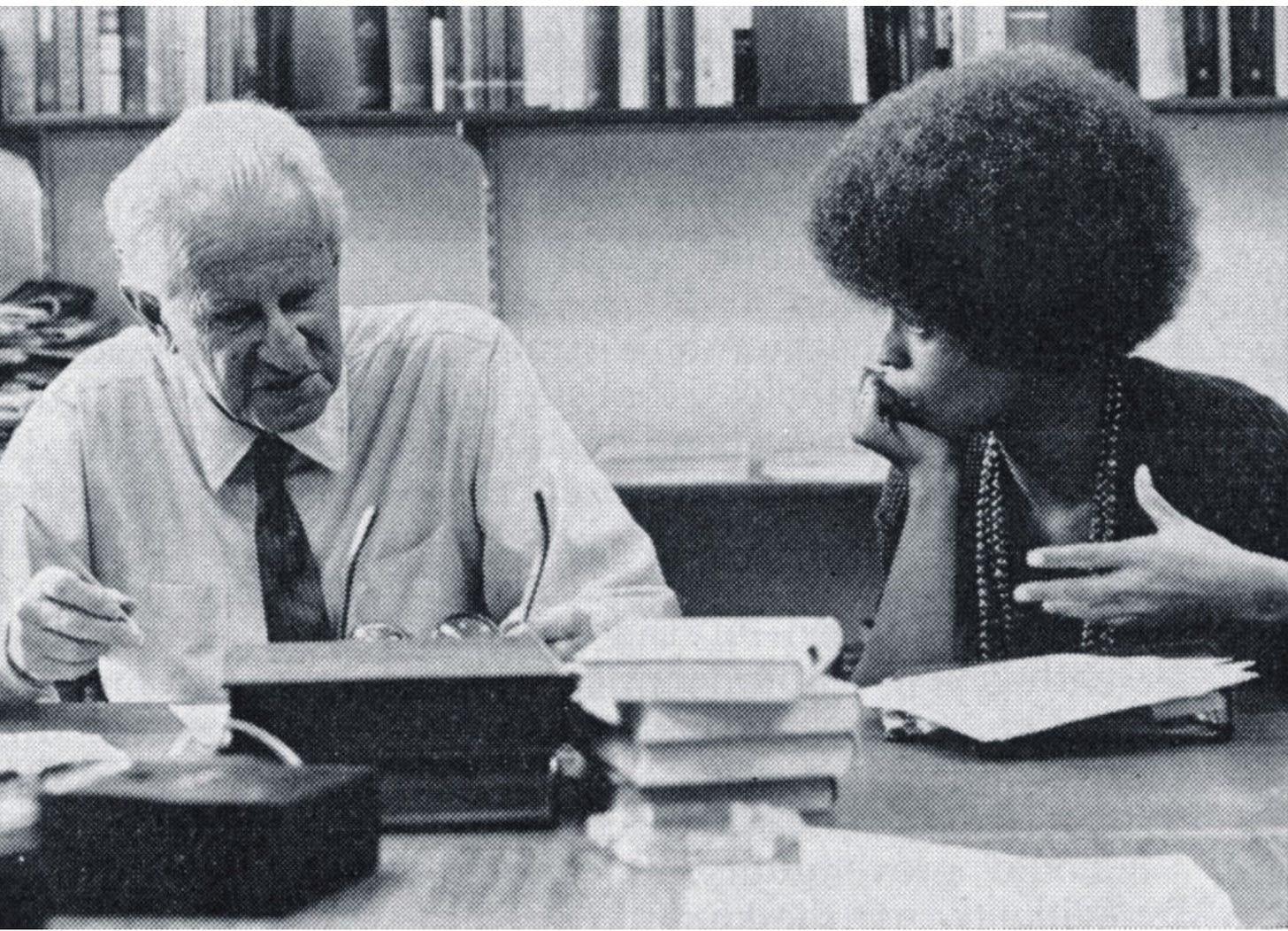

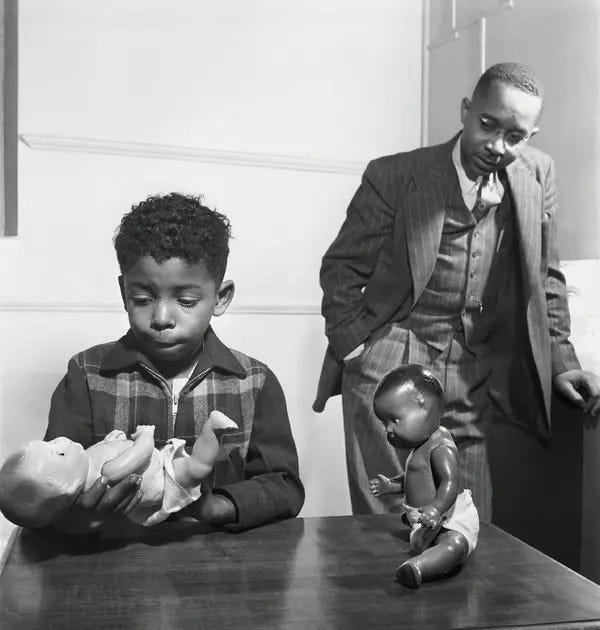

One of the most influential Jewish organisations that led this push for minoritarian liberalism was the American Jewish Committee. The Committee funded a Department of Scientific Research headed by Frankfurt Schooler Theodor Horkheimer. The most lasting output of the Department was a five-volume “Studies in Prejudice” series headlined by The Authoritarian Personality. The Committee also hired a young African-American psychologist named Kenneth Clark to conduct a study of the impact of school segregation on black students. This research was presented the NAACP in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case, and cited by Chief Justice Earl Warren in the final decision which declared segregated schools unconstitutional.

Boasians and the rise of Cultural Anthropology

If wokeism is really just an expression of the politics that naturally comes from sharing a belief in racial egalitarianism and a Christian moral background, and if the same Christian moral premises existed alongside a belief in significant race differences, then the shift to a belief in cultural determinism is surely one of the most important topics to examine when trying to understand the origins of wokeness. In the late 19th and early 20th Century Darwinist accounts of race dominated the academy, alongside Social Darwinism and the eugenics movement. Christianity was able to exist alongside commonplace belief in natural racial differences until the idea of race came under concerted attack in the 20th Century. Normalisation of the “cultural determinist” belief, (and the creation of taboo around the views it displaced) was largely driven by Jewish émigrés who feared or resented the American culture they encountered.

It wasn’t until the 1920s and 30s that anthropology moved in a more environmentalist direction, largely due to the influential work of the anthropologist Franz Boas and his students. Boas trained a generation of anthropologists that would come to dominate the newly emergent field, including Margaret Mead, one of the figures included on the Atlantic’s list. So influential were they that one scholar writes:

Much of twentieth-century American anthropology may be viewed as the working out of various implications in Boas’s own position.

Boas immigrated to the US from Germany in 1886. Having come from a left-wing Jewish family, Boas was by many accounts deeply concerned with combating anti-Semitism throughout his life, and this seems to have been a strong motive for his lifelong attack on social Darwinism and advocacy of cultural relativism.

Many of Boas’s students, as well as Boas himself, identified as much with the role of social critic as anthropologist, and were determined to overthrow what they saw as the racist and chauvinist norms governing the approach to the study of group differences. Boasians advocated for pluralism and spoke out against nationalism and racism. Boas took an adversarial stance to the cultural norms of his adopted home, he

Was viewed as one among a cadre of scholar activists working to both lay bare the true essence of anti-black racism in the United States, and, to help vindicate African American culture in the face of the degradation of segregation .

Boas was committed to the fight for racial equality throughout his life. Together with close friends he formed the American Committee for Democracy and Intellectual Freedom in 1939, an antifascist organisation designed to “discredit the theories of race being forwarded by the Nazis in Germany”.

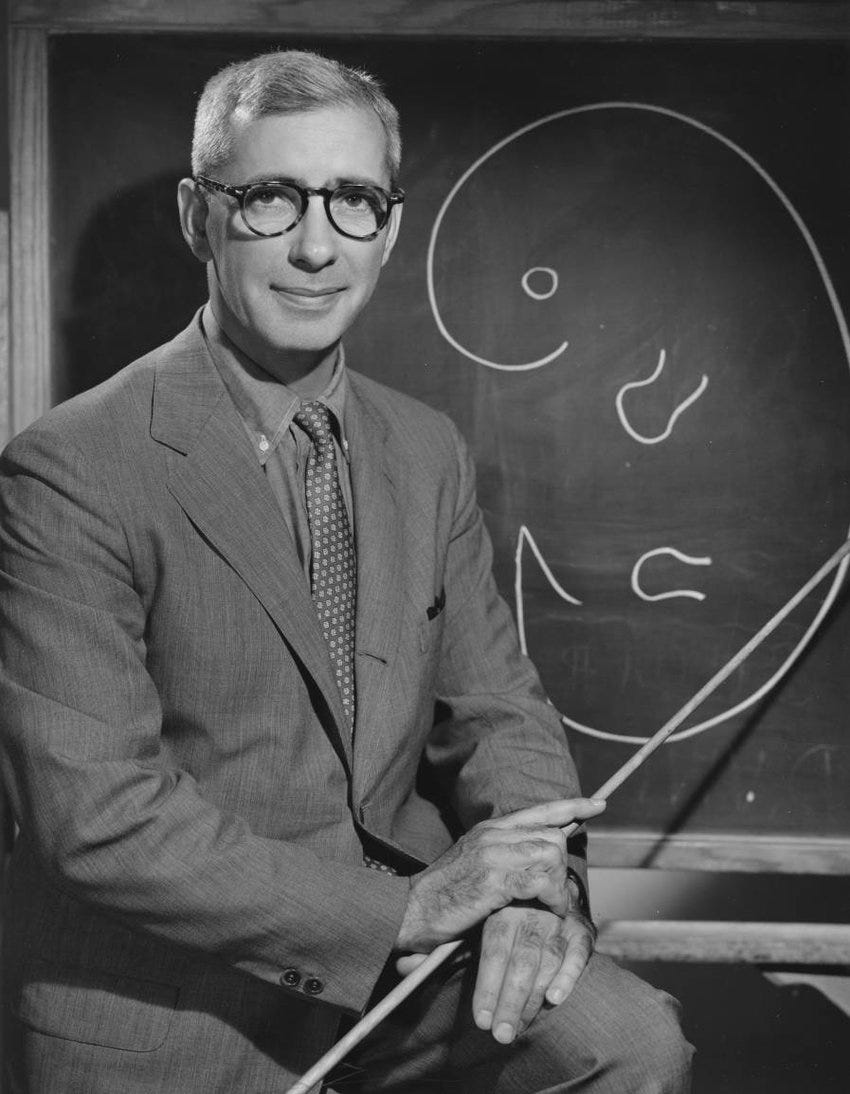

One of Boas’s most successful students was Ashley Montagu – born Israel Ehrenberg to a Jewish family in London’s East End – who completed a dissertation under Boas in 1937. Montagu arrived in the United States in 1931, and immediately focused his intellectual work on dismantling what he considered the dangerous idea of biological race, as well as attacking his new home of America for its racist past. His 1942 work Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: the Fallacy of Race, which was based on his dissertation, deconstructed the concept of race as one which developed in the 18th century as a response to slavery and colonialism. Practitioners of slavery in the United States continued to defend the myth of race into the 19th century as a way to legitimise their barbaric practice.

Montagu’s book received mixed reviews from other academics, and he misled other academics on his credentials. In her book The Evolution of Racism, Pat Shipman records that Montagu responded to his academic critics by branding them as “racists” who opposed him because of his Jewish heritage. In an interview later in his life, he explained this early opposition with the sensational declaration that “all non-Jews are anti-Semitic”, a statement Shipman used as the title of one of the chapters of her book. Montagu also described childhood experiences of antisemitism in London as formative. It does not seem Montagu ever embraced or assimilated to the American Christian culture after his arrival in 1931, rather, he critiqued the norms of White Christian society as masking oppressive dynamics which brutalised other races and women.

Despite the pushback Montagu faced within academia, he found great success as a populariser of science, finding a more receptive audience among the general public with the help of a media establishment eager to embrace him. Man’s Most Dangerous Myth became a bestseller, while his later work The Natural Superiority of Women was highly influential among the feminist movement.

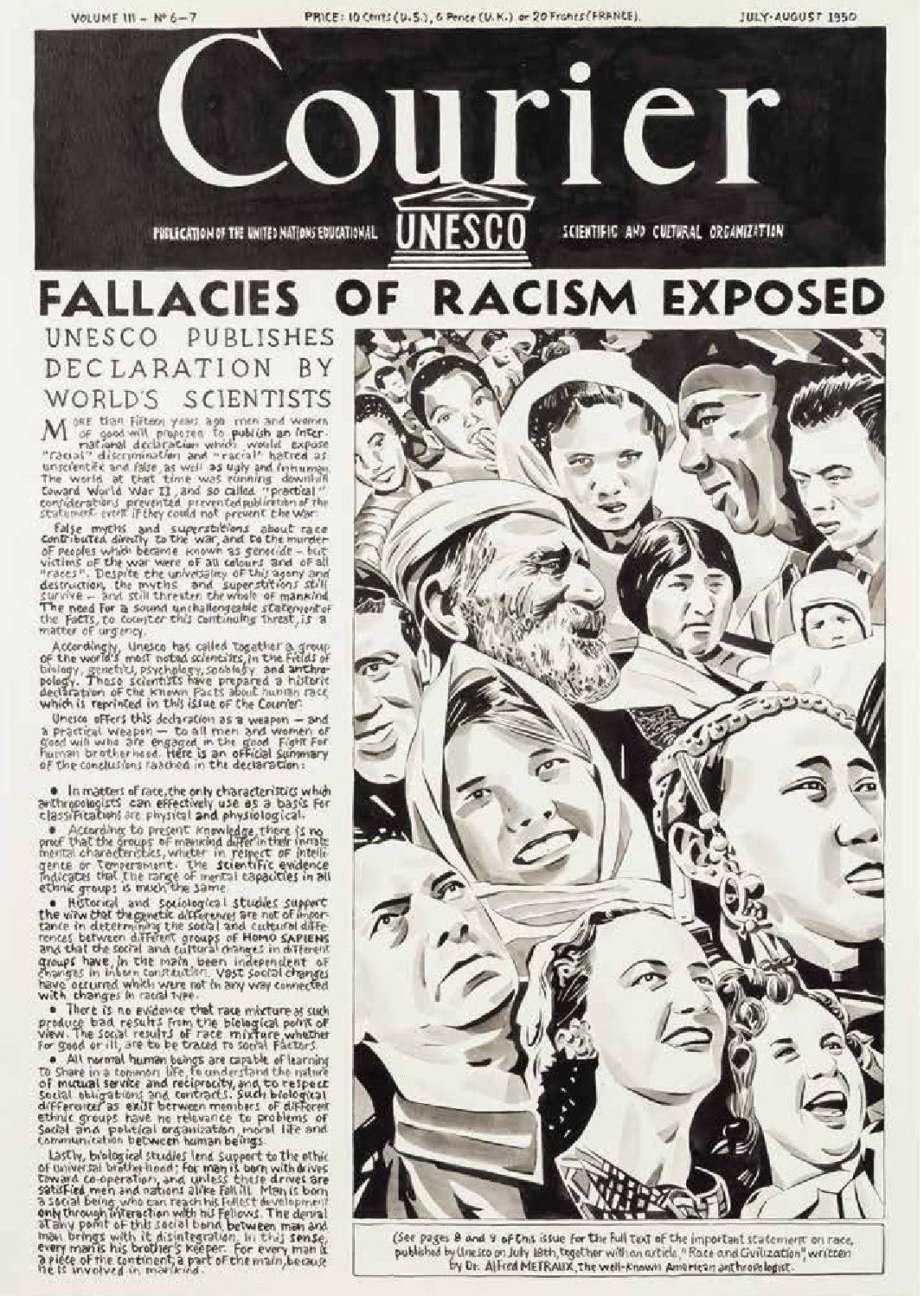

Montagu would have the honour of playing a leading role in UNESCO’s influential committee on The Race Question. In response to the racial beliefs at the center of National Socialist ideology, UNESCO convened a panel to produce a series of expert statements on race and offer a definitive condemnation of racism both morally and scientifically. The panel, chaired by Montagu, consisted of:

A team of ten scientists all of whom were recruited from the marginal group of anthropologists, sociologists and ethnographers affiliated with the scientifically marginalized groups of cultural anthropologists that were mostly students of Franz Boas at Colombia University in New York, and who perceived the race concept primarily as a social construct.

The final statement declared the beliefs of the “cultural determinists” who made up the panel to be scientific fact. One scholar notes that the panel were motivated by “widespread revulsion at the Jewish Holocaust.” The UNESCO statement on race gave official scientific credibility to the claims of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and formed the basis for several future UN conventions aimed at targeting racism. This was, according to a sympathetic historian, “the triumph of Boasian anthropology on a world-historical scale.” Within the United States, the UNESCO statement was another piece of evidence cited in the aforementioned Brown vs. Board of Education decision, as the most up to date understanding of race.

Looking at the record of Montagu and Boas’s work, it would be absurd to suggest their advocacy was motivated by a desire to assimilate to the Christian liberal values of their time. Rather, as the historian Mitchell B. Hart notes:

The positions taken by Jewish researchers were driven in large measure by ideological commitments and political goals.

The Boasian anthropologists, like the Frankfurt school and other New Left intellectual movements which sprung from the 1960s counter-culture, maintained a sense of otherness and opposition to the American tradition of liberalism they encountered. Many of the intellectuals at the head of these movements were exiles who brought with them from Europe a deep fear and mistrust of nativism, Christianity and Western Civilisation itself.

Describing this cadre of exiles in The Sea Change: The Migration of Social Thought 1930–1945, H. Stuart Hughes called them “the most abrasively critical, skeptical, and cosmopolitan within German-speaking Europe,” arguing that their arrival “was the most important cultural event of the second quarter of the Twentieth Century.”

Any attempt to trace the roots of wokeism that ignores this sea change, and the motive and character of this new intellectual elite transplanted into American society, is doomed to be but a partial explanation. This leaves anti-woke crusaders trading reductive and sometimes mystical theories of intellectual origin back and forth, trying to identify some kind of “woke” solvent in Christianity, classical liberalism or German idealism, which was destined to expunge every intellectual current but itself.

Notes

Wheatland, Thomas. The Frankfurt school in exile. U of Minnesota Press, 2009. Pg. 157

Wheatland, Thomas. The Frankfurt school in exile. U of Minnesota Press, 2009. Pg. 158

Liebman, Charles S. The ambivalent American Jew: Politics, religion, and family in American Jewish life, 1973. Pg. 157-158

Abrams, Elliott. Faith or fear: How Jews can survive in a Christian America. Simon and Schuster, 1997. Pg. 188

Friedman, Murray. The neoconservative revolution: Jewish intellectuals and the shaping of public policy. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Pg. 19

Friedman, Murray. The neoconservative revolution: Jewish intellectuals and the shaping of public policy. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Pg. 22

Stocking Jr, G. W. (1921). Ideas and institutions in American anthropology: Thoughts toward a history of the interwar years. Selected papers from the American Anthropologist, 1945, 1-50.

Hazard, A. Q. (2020). Boasians at War. Springer International Publishing. Pg. 32.

Shipman, Pat. The evolution of racism: Human differences and the use and abuse of science. Harvard University Press, 2002. Pg. 166

Duedahl, P. (2012). From racial strangers to ethnic minorities: On the socio-political impact of UNESCO, 1945-60. In Current issues in sociology: Work and minorities (pp. 155-166). ATINER.

Cannadine, D. (2014). The undivided past: Humanity beyond our differences. Vintage.

Sussman, R. W. (2014). The myth of race: The troubling persistence of an unscientific idea. Harvard University Press.

Hart, Mitchell B. “Racial science, social science, and the politics of Jewish assimilation.” Isis 90, no. 2 (1999): 268-297.

H. Stuart Hughes, The Sea Change: The Migration of Social Thought, 1930–1965. New York: Harper and Row, 1975.