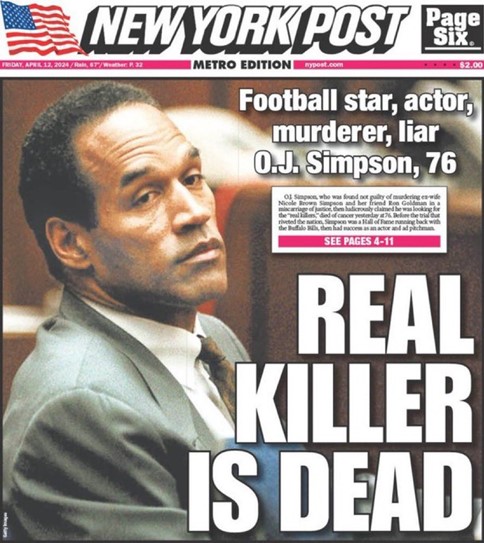

Thank You, O. J. Simpson

Black members of the live studio audience on The Oprah Winfrey Show celebrating news of the O. J. verdict on October 3, 1995.

1,095 words

I think it was the outcome of the O. J. Simpson trial in October 1995 which first introduced me to tribalism. As a young man I had seen it around me, especially among blacks — but also among Jews and Asians. I knew what it was, and I was fairly well-versed in its literature. For example, in high school I had read Richard Wright’s Native Son and Chaim Potok’s The Chosen. In college, they gave me W. E. B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk and Elie Wiesel’s Night. So when my black classmates talked loudly about their people and got defensive in the face of legitimate criticism, I didn’t bat an eye. When Jewish students didn’t interact much with gentiles, or when Jewish girls would suddenly lose interest in me once they learned of my gentile roots, I understood.

But tribalism for white people? That didn’t exist in my milieu as a young man. As a college student and beyond, I didn’t know anyone who spoke about it — except for the blacks. They prattled on about “white supremacy” and the like. But these were theoretical things they liked to complain about just to get attention. It wasn’t anything I took seriously, even in my Left-leaning liberal days. So, if white tribalism didn’t exist around me, how could I ever personally feel it?

I first felt it on the day an obviously guilty O. J. Simpson had escaped a guilty verdict in his murder trial. I vividly remember the news channels showing footage of black college students cheering as if it were a football game. This was their big victory? This was what they wanted to celebrate? It didn’t make sense. Yes, there had been the Rodney King verdict three years earlier — which even back then I knew had been correct, or at least reasonable. An inebriated King had just led the police in a high-speed chase and continued to resist arrest throughout his beating. The people he had been travelling with had complied with the police, and were thus spared any rough stuff. But even if Rodney King really had been a victim of excessive police abuse, and even if the narrative surrounding his victimization were true, hadn’t blacks gotten their payback already during the subsequent Los Angeles riots? According to Wikipedia, 63 people were killed in the mayhem, 2,383 were injured, and over $1 billion in property damage had been inflicted. Wasn’t that enough?

You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here.

When I saw so many blacks cheering O. J.’s acquittal, however, I realized that it had not been enough. They wanted a victory at the expense of whites once again, and it didn’t matter that in all likelihood an innocent white woman as well as an innocent Jewish –albeit white to them — man had been murdered by one of their own. At the time I had a dim understanding of what was happening. The volatile cocktail of tribalism and politics was brewing before my eyes, and I found it unsettling, to say the least. It was one thing when non-whites would crow about their accomplishments and demonstrate racial pride — which happened often during my college days. It was something else entirely when thousands of blacks across the country took my demoralization and the demoralization of people like me as a win.

See what I did there? “Of people like me.” I hadn’t thought in those terms so explicitly before. By this point, I had already red-pilled myself and renounced the counter-factual egalitarianism that had been pushed upon me in school. Race realism as I understood it was biologically and psychometrically sound. But that didn’t necessarily mean that whites had to be locked in the proverbial nation-prison with blacks, where political power was the very currency of survival. That didn’t mean that we, as dignified human beings, couldn’t separate average differences from individual differences and simply run a society based on merit. Whites had certainly shown such post-racial open-mindedness with Asians and Jews, who were surpassing them in many fields. So why couldn’t blacks do the same?

At the time of the O. J. verdict, I didn’t know the answer to this. But what I did know was that blacks couldn’t do the same. They could not overcome what I call their racial impetus. They could not help but wield the double-edged knife of racial pride and racial spite. Even in the face of grotesque levels of black-on-black violence, blacks as a whole still insisted on the nation-prison model of life in which they claw and scrape for every iota of power they could get — where there are no rules, and interracial mercy and kindness is seen as a weakness. O. J. was a hero not only because he had wasted two honkies, but because he got away with it. Win-win.

It was at that moment when I became a white man.

I knew that the same people who, oblivious to all sensitivity and decorum, cheered for a murderer’s freedom would cheer just as hard for the black thug who might murder me one day. They would want that person to walk free as well, justice be damned. I then imagine this attitude being extrapolated to my family members or my still unborn children. Exactly how betrayed and resentful would I feel watching these same black college students applauding the murderer of my daughter — if he was black? From there, the extrapolation continued. My cousins and distant relatives. My friends, neighbors, and colleagues. Soon, I started sympathizing with whites I wasn’t related to and didn’t know. In my mind, a line began to be drawn between insider and outsider, and potential friend and potential enemy — and that line kept getting longer and longer.

This is how love of one’s family expands into love of one’s ethny. Thanks to those euphoric blacks caught up in the travesty that was the O. J. Simpson verdict, I began to understand I had something in common with whites I didn’t know. And it wasn’t simply potential victimhood. It was also the realization that we as a group must hang together in this prison-nation that blacks have foisted upon us, or else face the vicissitudes of history once we get crowded out of power for being too fair-minded toward people who clearly wish us ill.

I would therefore like to thank O. J. Simpson, who died earlier this month, for this lesson, and preserve his memory for posterity. That he should rot in Hell should go without saying.