Britain Hangs Itself, by Jared Taylor

Thumbnail credit: © Joe Giddens/PA Wire via ZUMA Press

This video is available on Rumble, BitChute, and Odysee.

Every year, I make a new year’s resolution: not to be surprised any act of self-loathing by white people. I’m prepared to be disgusted; that happens all the time. But every year, something catches me by surprise.

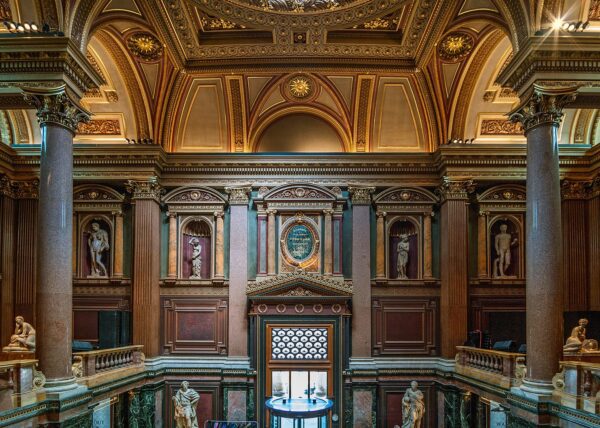

Just this month, the Fitzwilliam Museum, associated since its founding in 1816 with Cambridge University, reopened after five years. It was closed for what’s called a “rehang.”

That’s when a museum takes everything down and completely reorganizes its exhibits. Of course, the new “hang” was going to apologize for everything British. We knew that. But there was one little touch that I didn’t see coming.

The museum owns this famous painting of Hempstead Heath by John Constable.

It’s back on exhibit, but with a warning. The painting has a “darker side.” It implies that “only those with a historical tie to the land have a right to belong.”

You better not just admire this loving depiction of bucolic England.

You’ve got to stand there and think, “I bet all those people are white. This is awful. How racist!” The whole rehang is in this spirit.

The Fitzwilliam is one of Britain’s flagship museums, with over half a million objects. It helps set the tone for how Britain sees itself.

Its galleries used to be arranged in the usual way, with chronological displays of masterpieces.

Now, the pictures are grouped by “theme,” such as “identity,” “migration and movement,” “inner lives of women,” and “men looking at women.” Paintings from different eras and in completely clashing styles hang next to each other to bring them into “thought-provoking dialogue” – except that you know exactly what you are supposed to think.

In the “identity” gallery, you now have portraits by the 18th-century artist William Hogarth right next to this celebration of miscegenation called “An 18th Century Family.” It’s by a black woman named Joy Labinjo.

Her work takes up a whole wall, but, well, black people take up a lot of space. The Guardian, in an article called “Inclusivity shouldn’t be controversial,” approvingly calls this juxtaposition “subversive.”

Right. A museum’s job is subversion. And that is why we have a black lady dressing her hair, next to portraits from an earlier, better time.

Here’s another recently acquired treasure, more black ladies painted by yet another black lady.

The notice in the Identity gallery explains that all those old, boring Hogarth-type paintings of rich people were “vital tools in reinforcing the social order of a white ruling class,” as if Britain should have had a black ruling class.

And, you see, people had their portraits painted as a way to grind down the poor.

It’s all part of the awful legacy of what used to be called Great Britain. The gallery note explains that, “Unless we understand our histories, and the images that embody them, we can’t hope to repair some of the damage that those legacies caused.”

The Fitzwilliam repairs some of the damage with a Nigerian man’s sculpture of a Jamaican dancing on the British flag.

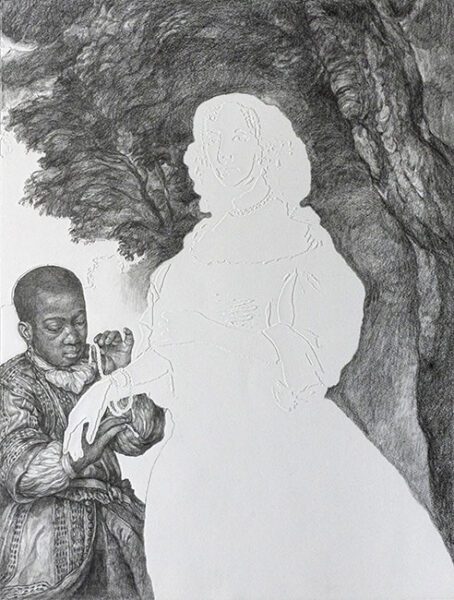

Here’s more damage repair. Black lady artist Barbara Walker “turns the tables on European art,” as one journalist happily put it.

She copies a historical painting with a minor black figure and bleaches out the central white figure. She’s like the American black, Kehinde Wiley, painting Napoleon out of a famous portrait and painting in a black man.

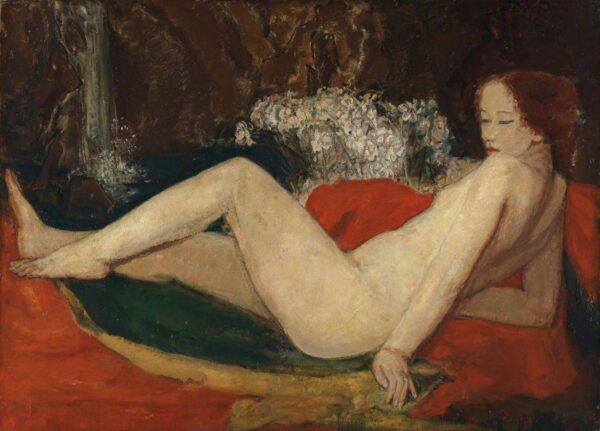

Needless to say, the Fitzwilliam is proud to display – for the first time ever – the first known British painting of a female nude by an open lesbian, Ethel Walker’s 1916 Silence of the Ravine.

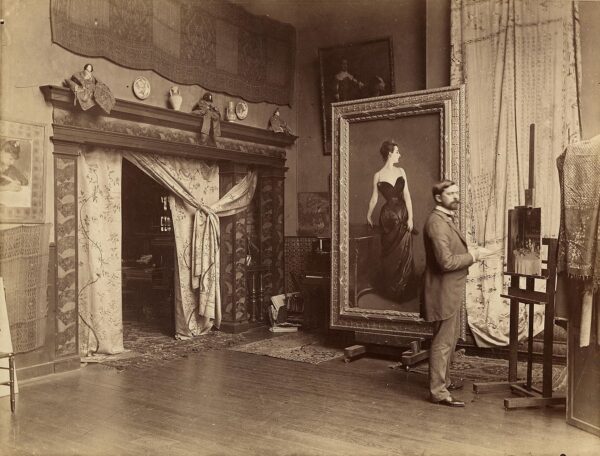

And paintings by the famous portraitist John Singer Sargent now come with a breathless reference to “speculation he led a secret, queer life.”

Queer, mind you, not gay.

The sign in the Migration and Movement gallery explains that “while some people chose to leave their homes, global conflict, discrimination and European colonialism meant others fled or were exiled by force.”

But the Fitzwilliam’s great and abiding sin is that its namesake and founder, Richard Fitzwilliam, had a grandfather who helped found the South Sea Company, which did a little slave trading.

The shame of it! And so, as part of this grand reopening, the Fitzwilliam has put on what will be the first of three especially self-loathing exhibitions, this one called Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance, with Barbara Walker whiting out the white man, as usual. It comes with a trigger warning: “This exhibition explores themes of enslavement and racism. It includes depictions of slavery and objects linked to violence and exploitation.”

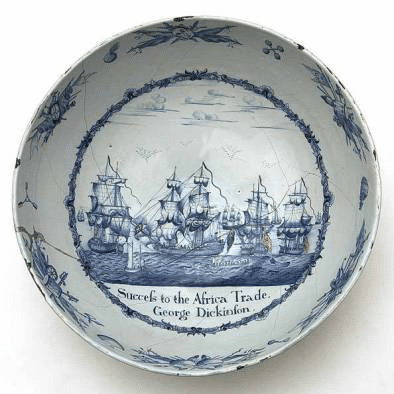

Except that the museum had hardly anything that had to do with slavery. No chains, no whipping posts, no slave-ship manifests, so it has to make do with containers for Caribbean crops, chairs made of trees allegedly cut down by slaves, and trinkets used to trade with natives. Imagine the curators’ joy when they found this punchbowl that celebrates “success to the Africa trade.”

The Fitzwilliam had such a shameful lack of actual paintings of Negroes for this exhibit that it had to borrow Portrait of an African Man from the Netherlands and Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit from the Royal Albert Memorial Museum.

As you saw earlier, though, the Fitzwilliam is making great strides with its contemporary affirmative-action collection.

The museum website notes sorrowfully that “we still benefit from Atlantic enslavement in terms of our finances and collections and are making a commitment to reparative justice,” whatever that is.

Ironically, even Wikipedia notes that although the South Sea Company had a monopoly on the slave trade to South America for a few years, it never realized any significant profit from its monopoly.

Doesn’t matter. The Fitzwilliam was built on blood money and must apologize forever. It’s following the priorities the 135-year-old British Museums Association sets for its 580 institutional members: “Address the climate crisis” and “decolonize and democratize [their] collections.”

The whole country is officially obsessed with blacks. For example, Trafalgar Square in the center of London has a plinth at each of its four corners.

Three bear statues of British heroes but this one was built for an equestrian statue of Willim IV that was never made.

In 2003, control of the plinth was turned over to the City of London, which has put up insulting modern rubbish such as this Blue Cock – here is another one of the German lady-artist’s masterpieces, Rat King – and this blob of whipped cream, which is equally inspiring and beautiful.

Now that London has a Pakistani mayor, Sadiq Khan, the fourth plinth has gone black

What’s up there now is called “Antelope,” a statue – by an African, of course – of a giant black man and a midget white man.

Here is the sculptor boasting at the unveiling. [antelope] 0:12 – 0:22

In 2026, the plinth will get a bronze statue of “everywoman” by an American black woman named Tschabalala Self.

She says she depicts black female bodies that “defy the narrow spaces in which they are forced to exist.

No narrow spaces for this lass, just like the paintings by black women at the Fitzwilliam.

I’m guessing “everywoman” will be about as tall as this black woman, also in London, standing next to her sculptor, yet another American, Thomas Price.

What appears to be the same giant black woman, takes up a lot of space in front the main train station in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

When she was unveiled, the Muslim-Moroccan mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb – here on the right – said he thought she would become Rotterdam’s most photographed attraction.

He also said, “She is the future, our future, and this city is her home.”

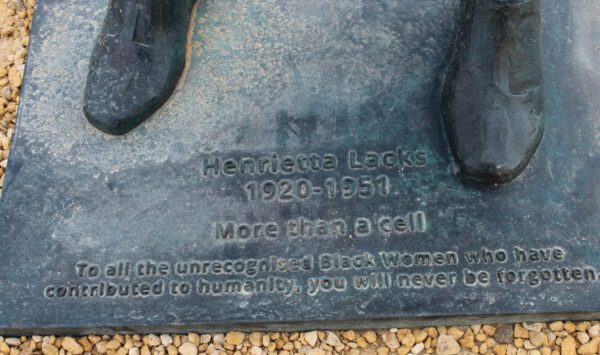

In Bristol, England, there is a statue of a real black woman, an American named Henrietta Lacks, who had no connection with Britain at all.

You will recall that Bristol, in a BLM frenzy, tore down the city’s main benefactor, Edward Colston, who had stood in the center of town for 129 years, and pitched him in the river.

Henrietta Lacks was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1950 and treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital for nine months but died at age 31.

Doctors took tissue samples and cultured the first human cell line capable of sustained multiplication outside the body. As was the practice at the time, the doctors didn’t ask permission. The cell line has been useful in medical research.

When the statue was unveiled in 2021, there was much joy at the announcement that this was the first public statue of a black woman by a black woman in all of British history.

Henreitta only produced a few diseased cells, but the base of the statue says, “To all the unrecognized Black women who have contributed to humanity.”

Why is the statue in Bristol? There must be a lot of unrecognized black women forced into narrow spaces there.

And, on and on it goes. The same year Henrietta was unveiled, a giant bust of George Floyd went up in Brooklyn, another black hero whose only achievement, pardon me, was to die.

Why do white people apologize for their own history – their own existence, really – and glorify others, especially blacks? No other people could ever be tricked into this. You can blame Christianity, blame the Jews, blame pathological altruism, blame two world wars. Even taken all together, white self-loathing runs so violently against human nature, you wouldn’t believe it if you didn’t see it, day after day after day.

And as craven whites put yet more non-whites in charge – of museums, cities, associations, universities – they will drive the country into ever-more-degrading expressions of contempt for you and for me, and for every white man who ever lived.

I see no national solution. We can build fortresses of pride and sanity in our daily lives, our families, our communities, and expand from there. But a nation whose elites tell you that this painting has a dark side of exclusion and racism is lost.