The Futility of 'Helping' Africa, by Anastasia Katz

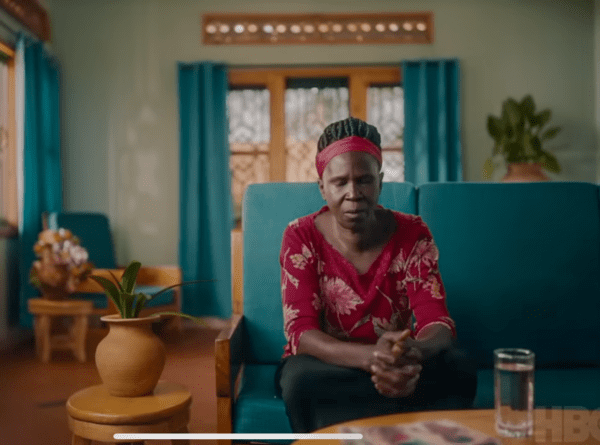

Savior Complex, HBO Original, 2023

“Savior Complex,” a three-episode documentary series on HBO Max, shows us the world of Christian missionaries in Africa through the eyes of young white women who dedicate their lives to helping Africans, but who end up at odds with each other and with the Africans. The series tells the story with interviews and social media content, and it gives both sides a fair hearing. Ultimately, it is an indictment of social media culture and the missionary system as much as of the women. There is another message: Don’t try to help Africans.

Renee Bach grew up on a farm in Virginia, where her parents ran a program to help special needs children. She was homeschooled and attended a Baptist church. During her senior year in high school, she was inspired by a sermon and volunteered for a mission to Uganda. She went to the city of Jinja, which is home to several hundred nonprofits, all presumably helping poor Ugandans. It was the first time she had left the United States.

Miss Bach’s fellow missionaries were all young white women. In some ways, the mission was like a vacation — the ladies went on a wildlife safari, and their accommodations had a swimming pool — but feeding the hungry was not pretty. The program gave villagers the only meal they would have that day. A black man would typically beat children back with a stick. Once the villagers were properly lined up, the missionaries fed them bread and beans.

Miss Bach found the work rewarding, and felt a calling to continue when it was over. In 2009, at age 19, she founded a nonprofit called Serving His Children (SHC). She moved into a house in a Jinja slum and started her own food program. Her mother, Lauri Bach, became the US director.

As her work became known in Jinja, the local hospital called Miss Bach and asked if she would take in some malnourished children whose parents could not afford to keep them in the hospital. The children needed a place to stay, where they could eat and gain weight. Miss Bach agreed and decided to end her feeding program and turn Serving His Children (SHC) into a malnutrition rehabilitation center.

Filmmakers interviewed Dr. Abner Tagoola, the Head of Pediatrics at Jinja Hospital. He said his ward was full of severely malnourished children. The hospital was built to handle 150 children but 250 were admitted every month, so many were discharged well before they were healthy. He said of Miss Bach, “Her coming on board was really welcome. For the children who have discharged, she was able to give them shelter in a very clean environment until they were fully rehabilitated.”

Miss Bach hired a Ugandan woman named Constance Alonyo as head nurse. She weighed and measured the children to track their progress. She told the filmmakers she had trouble remembering the names of the white women who worked at SHC. “I just call them all the same. They’re whites.”

Miss Bach’s only medical training had been a two-week course before she left for Africa, but she picked up skills by watching Mrs. Alonyo. “I was taught by people like Constance how to put an IV in or how to clean a wound.” Sometimes a child had to be taken to the hospital, and doctors prescribed medicine. Miss Bach began buying frequently prescribed medicines in bulk.

Miss Bach kept a blog of her work, and received nice comments such as, “You are an angel.” Donations trickled in. With time, Miss Bach became more skillful at using her blog to raise money. She learned that “the more dramatic a story was, the better the response was . . . everyone wants to make a difference.”

As healthy children went home from SHC, word spread in the villages. Mothers who could not afford medicine went to SHC to get it for free. Parents began to bypass the hospital and bring sick children directly to SHC. Some were near death, and Miss Bach said that neither she nor her organization were prepared for that. Sometimes parents showed up carrying children who had died on the way. “There’s so much death,” Miss Bach said.

More than once, Miss Bach had to rush a child with labored breathing to the hospital, and found out how poor medical care is in Uganda. She would go from hospital to hospital, but none would admit the dying child. Either the hospital had no electricity, or the oxygen concentrator was broken, or their oxygen source was already in use. It seemed impossible to get the children proper care, and Miss Bach felt responsible for them. When a baby died because she could not find a hospital, Miss Bach told the story in her blog, and donations increased.

Sometimes, Miss Bach returned to the United States to raise money. In one of her speeches, she told the story of a mother who brought sick twin babies to the hospital. Ugandan doctors said the babies were going to die. Miss Bach told her donors:

When the hospital called me, they said, “We have tried.” And this is what they always tell me: “We have tried, we have tried to help these children, and we have failed.” So, they call me, the 21-year-old with no medical degree, to come and pick them up. So, I put my trust in the Lord to save them, but also thinking in the back of my mind, preparing for the worst. But God was preparing me, so I would watch a miracle unfold.

The twins survived. “I don’t even have a medical degree,” said Miss Bach, “so it’s just a testimony that God is the one who is saving those children.”

Miss Bach’s fundraising was successful, and she was able to hire more staff and buy medicine and equipment that the local hospital was “grasping at straws” to obtain. She was praised by the American media and was proud of what she accomplished. She adopted a Ugandan orphan named Selah.

Jackie Kramlich, a young newlywed and nursing student, found Miss Bach’s blog and it made her want to “experience the world.” Her husband Chris Kramlich was also inspired, and the couple asked if they could volunteer at SHC. Mr. Kramlich said, “That’s what you would do if you took Jesus seriously.”

After Mrs. Kramlich graduated from nursing school, the couple went to Jinja, eager and excited. They soon realized how serious the job was. “It’s so explicit on the blog,” Mrs. Kramlich said, “But I think until you’re there and you see it, and you smell the smell of it . . . the skin that is almost decomposing to a degree because it is so malnourished, and you just kind of realize, woah, this is really intense.”

At first, Mrs. Kramlich was impressed by Miss Bach. She saw her giving injections and she seemed competent. Then she saw where children were on IVs. It was almost like an intensive care unit (ICU), and Mrs. Kramlich thought it was over her head as a nurse. She said Miss Bach was doing the work of a doctor — diagnosing children and prescribing medicine.

Mrs. Kramlich said she got vague answers when she asked Miss Bach why she was giving the children certain medications. After a child died, Mrs. Kramlich looked at his chart and thought the dosages were high. She went through the files of children who died at SHC; many died within five days. She researched malnutrition, and found that a big risk during rehabilitation was refeeding syndrome. A malnourished person can’t handle a lot of food right away, and should “start low, go slow.” Mrs. Kramlich said, “Giving a child little sips that they can manage out of a cup would be better than an IV drip. Because, you start pumping a child full of fluid, that’s a lot of pressure on the heart, and the heart can just give out.”

She noticed that Miss Bach wanted to give IV drips right away when children arrived, and she tried to explain that this was risky. Mrs. Kramlich said Miss Bach replied, “I know this sounds kind of weird, but sometimes I feel like God just kind of tells me what to do.” Mrs. Kramlich was worried. “I think Renee bought into a fantasy that she was ordained and special and set apart, and that she was just naturally a doctor.”

Missionaries had a saying: “God doesn’t call the qualified, he qualifies the called.” Mrs. Kramlich’s interpretation was that if you feel called to do a job, that will motivate you to get the qualifications. She believed Miss Bach thought that if a person felt called, God would give him intuition so he would be able to do the job without training. “It felt like there was nothing I could do to get through to her,” Mrs. Kramlich said. “I was there to be a nurse. And so, if you don’t want my experience, what am I to do?”

Mr. Kramlich said that his wife typically came home feeling frustrated because she saw the children being cared for incorrectly. He believed Miss Bach brushed aside his wife’s advice because she needed to be the person through whom God was working. “I think that Renee felt if she took advice from other people, that somehow that would lessen her value to the story, of being someone God works through to heal these children.”

Mrs. Kramlich had a falling out with Miss Bach. A baby named Patricia was close to death, so Miss Bach started a blood transfusion. She then called Mrs. Kramlich because she suspected Patricia was having an anaphylactic reaction. Mrs. Kramlich wondered why she hadn’t been called sooner. She told the filmmakers, “I asked her, ‘What were the vitals before you started?’ and she was just like, ‘I don’t really know. I was in such a hurry.’ ”

They took Patricia to a hospital, where they waited three hours to see a doctor. Patricia was treated for a few days, and then the hospital called and asked Miss Bach to come get her. A wound was forming on Patricia’s cheek, but the doctors said nothing about it. Mrs. Kramlich frantically tried to figure out what was causing the wound. She sent photos to doctors in America, who said it was necrotizing fasciitis, a flesh-eating bacteria, and recommended treatment. Patricia recovered, but her face was scarred.

Mrs. Kramlich looked at Patricia’s records from the hospital, and realized that they said Patricia had necrotizing fasciitis. She asked Miss Bach if she had read that, and Miss Bach said she didn’t think the doctor knew what he was talking about. Mrs. Kramlich was furious that Miss Bach had ignored the diagnosis.

The African nurse Mrs. Alonyo noticed the tension between the two women. “The whites, most of the time, I don’t know their grudges, how the enemy things happen. But Jackie [Kramlich], she came and told me that Renee [Bach] does not want to be advised.” The head nurse said she didn’t know what Miss Bach was thinking when she started the blood transfusion, but she was not concerned. “I can just accept it was a mistake.”

Mrs. Kramlich couldn’t accept the mistake. “Kids are dying because she’s doing things that she shouldn’t be doing.” SHC’s records showed that 26 children died in their care in 2011, while 129 went home healthy. Mrs. Kramlich quit, and wrote a letter to Lauri Bach, Miss Bach’s mother:

It seems that SHC began as a basic feeding program but has now progressed into a much more intensive critical care unit. This progression was relatively fast and, in our opinion, has not allowed time for proper staffing in the medical arena. Although Renee is very intelligent, quick to catch on, and unquestionably dedicated and motivated, the fact remains that she has no formal training in the medical practice with which she works every day. This raises ethical concerns.

Lauri Bach thought Mrs. Kramlich’s accusations were unfair, but she and her daughter took action. The nonprofit hired a Ugandan doctor, Dr. Aggrey. Eventually the staff included a full-time doctor, a part-time doctor, six nurses, three social workers, a pastor, a nutritionist, and an agriculturalist who taught families of malnourished children how to grow their own food. Mrs. Bach said there were still a lot of children who had first been taken to witch doctors, and by the time they arrived at SHC, it was too late to save them.

After Mrs. Kramlich left SHC, she and her husband stayed in Jinja and volunteered for a different organization. They kept in touch with head nurse Mrs. Alonyo, who told them that although doctors and nurses were hired, Miss Bach “was still the one doing everything.” Mrs. Kramlich didn’t think Miss Bach could change: “I think she truly believed that she was more capable of treating these children than any other trained person.”

Mrs. Kramlich talked to a fellow missionary named Kelsey Nielsen. The two decided they had to stop Miss Bach, so they went through her blog posts to find examples of bad treatment. Miss Nielsen copied the “evidence” to her own blog, and some people who read it said that they had also seen Miss Bach doing things wrong.

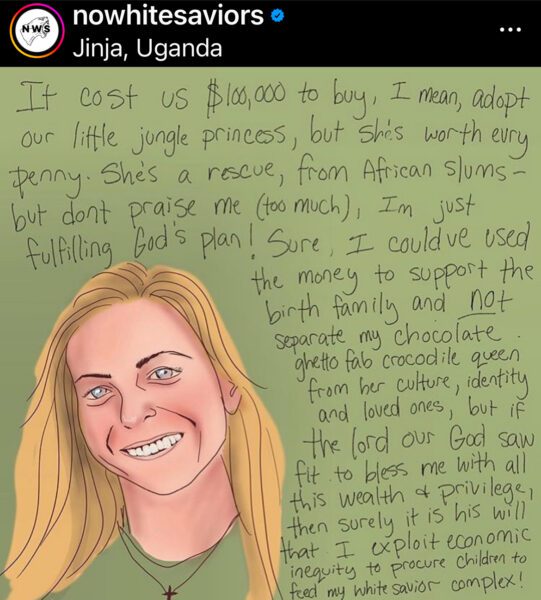

Miss Nielsen had an about-face on missionaries. She teamed up with a young Ugandan woman named Olivia Alaso and they started an anti-missionary activist group called No White Saviors. Miss Nielsen had originally hired Miss Alaso to be a social worker for her evangelical charity, but Miss Alaso told the filmmakers she quit that job because she “had no power” at Miss Nielsen’s charity. No White Saviors’ social media pages and podcast became popular, and Miss Nielsen called herself “a white savior in recovery.”

Maybe I wasn’t the worst white person that came into Jinja, but the more I learned . . . about the harm that I caused, the harm that other white people have caused here, the more I’ve realized just the complete miseducation that we receive internationally about the African continent . . . As white people, we desire to help and we know that needs exist, but we don’t want to . . . acknowledge . . . how that need was created and why it’s continuing to be perpetuated. So much of the white savior complex is definitely, I believe, a legacy of colonialism.

During the colonial era, the British built hospitals, roads, schools, and houses in Uganda. Miss Alaso said the Ugandans were told they should be grateful, but she believed whites wanted only to control Africa’s people and natural resources. “Are we really independent?” Miss Alaso asked. “Missionary work is an extension of colonialism. You have to force me to believe in your god who helps you justify your way of life.”

Miss Nielsen felt she was honoring God when she went to Africa, but she now believes she was indoctrinated. She said missionaries in Jinja tend to be young, single, white women from an evangelical background, because “it is a permissible form of female leadership and female power that in America, they wouldn’t be able to have in their marriage or a church setting, but we can have that by starting a nonprofit in Uganda. . . . It clicked for me that as a white woman coming from America, we don’t want to have to give up any power, any privilege.” Miss Nielsen believed Miss Bach did not want to give up power or privilege to the medical staff she hired. She and Mrs. Kramlich organized meetings at other white expats’ homes to talk about Miss Bach.

Elizabeth Nicholson is an American who had worked at a nonprofit in Uganda for 11 years, and knew Miss Bach. She was appalled when she heard Mrs. Kramlich’s and Miss Nielsen’s accusations. She contacted the US embassy, but the embassy told her it was up to the Ugandan authorities. She filed a report with a police captain who was a good friend. He later told Miss Nicholson that “three very important police from Kampala [the capital of Uganda] came and said, ‘Drop it!’ ”

Miss Nicholson next went to the head of the hospital and told him that Miss Bach was “killing children.” The District Health Officer (DHO) went to SHC and ordered Miss Bach to close, telling her that if anyone were still there after 5pm, he would take her to jail. He did not say why SHC had to close or what Miss Bach had to do to reopen. Miss Bach was shocked; she had no idea the women were conspiring against her. She was distraught because there were 18 children in the facility who had not yet recovered. Their mothers pleaded that she keep them in treatment, but Miss Bach was forced to send them home.

Miss Nicholson found out that Serving His Children was not licensed to operate as a medical clinic. Mrs. Kramlich said of Miss Bach, “There was a real superiority complex that was kind of like, ‘Oh, that’s cute, Ugandan law. But we answer to our own rules.’ ”

Lauri Bach flew to Uganda to help her daughter. The documentary showed that Serving His Children had a license to operate a “heath unit,” but the license was expired by the time of the closure. Mrs. Bach checked records and found that 105 children “did not survive the condition of severe acute malnutrition.” However, 835 children were rehabilitated and discharged. Their mortality rate was 11 percent. The largest hospital in Uganda that treated malnourished children had a 14 percent mortality rate. According to Dr. Esther Babirekere, the director of nutrition at Mulago Hospital, “When a fatality rate ranges from 10 to 15 percent, that is a good achievement.”

The Health Department’s documents stated SHC was closed because children with tuberculosis had been mixed with other children. The recommendation was, “All children need to be referred to other health facilities and this facility stop treating children until their issues are cleared.”

Miss Bach learned that some of the children she was forced to send home had died. She was angry to think that the people who had ruined their chances for survival had accused her of “slaughtering kids.”

The documentary included an interview with SHC’s Ugandan social worker, Jackie Atim. She taught poor villagers about malnutrition and told them where help was available. She said that villagers viewed whites as their saviors: “It was my role to recruit these mothers. . . . and when she hears there is a mzungu [white person], you would find she would say, ‘Oh, ha! I’m going to be saved.’ ”

At first, Miss Atim was grateful for Miss Bach’s compassion and aid; but after she got to know her, she felt looked down on. “I don’t know if it was because she was a white, and she was working in our country which seemed to be very poor, but she didn’t respect us. It was like she knew more than the doctor, more than the social workers, the nurses. . . She was even teaching them what to do, telling them, ‘Do this; in America, we do this.’ ”

Miss Atim feared losing her job if she complained to Miss Bach, so she talked to Dr. Aggrey. The doctor thought Miss Bach’s intentions were good, but she would not take advice: “She would do things as if she was a medical personnel. Those [patients] who were lucky benefitted.” Dr. Aggrey also did not want to talk to his boss. “I had no powers,” he said.

After Dr. Tagoola, head of pediatrics at Jinja Hospital, found out that SHC had set up a do-it-yourself ICU, he was not surprised it was shut down. However, he did not blame any deaths on Miss Bach. Sixty children die every month in his own hospital. He believed Miss Bach’s efforts were saving lives, so he helped her get started again with a government-run malnutrition center.

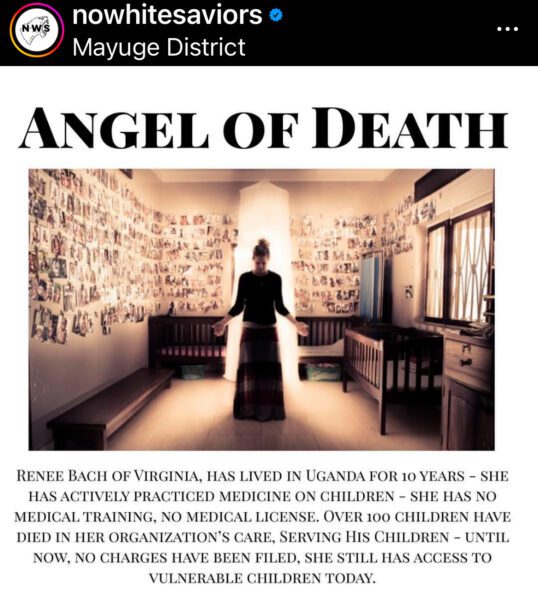

Miss Nielsen was angry that Miss Bach had opened a new center, “after 105 children died under her watch.” She and Olivia Alaso attacked Miss Bach on their No White Saviors video channel. Miss Alaso said on a broadcast, “I feel that this should be a lesson to the rest of the world, that white people are not going to move to any African country and do what they want.”

Miss Bach was astonished when she read a post on SHC’s Facebook page and learned what Miss Nielsen thought of her:

I had this CRAZY thought today. You should *pray* about renaming your organization KILLING HIS CHILDREN. The whole “Serving” thing doesn’t really fit. Unless you’re *serving* *HIS* children medical malpractice and manslaughter with a side of white privilege, neocolonialism, Evangelical oppression. Must be nice to experiment on children medically with the help of YouTube videos and unending praise from your literal unintelligent and ignorant donor base. Please get out of Uganda willingly before I continue pursuing legal means to have your founder and board thrown in AMERICAN prison for the international crime you are guilty of.

Miss Bach didn’t know what “neocolonialism” meant, and she laughed it off, thinking Miss Nielsen would soon move on, but she became a regular target of No White Saviors. People began threatening her online.

“Take her. We’re going to lynch her.”

“If one bytch (sic) deserves to be raped and killed by the natives is this one here.”

“…skinned alive and doused with rubbing alcohol…”

“Take her kids and torture them while she watch it. And after that kill her.”

Miss Bach’s father feared for her safety, and urged her to leave Uganda right away. She moved back to Virginia and kept a low profile. She adopted a black American baby, but was afraid to announce the adoption on social media. Her Ugandan adopted daughter — in the series, she seemed to be late-elementary-school age — was homesick. Miss Bach said, “I feel like Selah lost her entire identity as a Ugandan citizen . . . . I think one of the hardest parts for her is that we live in a staunchly, straight-up, white Southern community. Her whole life, she has just wanted to fit in . . . . She can’t really do that as easily here.”

From America, Mrs. Bach tried to keep Serving His Children going, but donations dropped by 50% after No White Saviors started badmouthing it.

A locust swarm approached Uganda, threatening the food supply, and Miss Bach said: “The irony is, Kelsey [Nielsen] and her No White Saviors followers, they think they’re saving Uganda from just unthinkable harm and damage, but who’s serving these kids now? Is it Kelsey? She hasn’t posted about it online . . . .” Who was going to feed hungry Ugandans after the locusts had gobbled up crops?

No White Saviors used a crowdfunding platform to hire a Ugandan lawyer, Primah Kwagala, to pursue a criminal case against Miss Bach. Miss Kwagala was shocked by the allegations. “In their opinion, she [Miss Bach] was responsible for so many murders. But when I would ask, ‘Did you see this?’ They would be like, ‘No, someone told me that.’ ”

Miss Kwagala found out that Serving His Children had been licensed for only one year. She looked at the nonprofit tax exemption documents, and found that SHC earned a total of $1,493,329 in the 10 years it had been operating. “Money comes with influence,” Miss Kwagala said, “And with that, comes the silence of the authorities as well. The healthcare system in Uganda was set up basically by missionaries. So, Renee was viewed as bringing resources and development in the community.”

Miss Kwagala tracked down two mothers whose children were allegedly harmed by SHC. Both earned meager wages and lived in huts. Kakai Annet said her son Elijah had been vomiting, so she brought him to SHC, where a white lady examined him, then gave him back to her. Elijah died three days later. Miss Annet spoke against SHC on a local radio station, because she didn’t know why her son died. The other mother, Gimbo Zubeda, brought her son, Twalali, to SHC after he became sick. She said a white woman took her son away from her, and did tests on the boy before he died.

Miss Kwagala found that Miss Bach had made social media posts about these children, but she found no direct evidence tying Miss Bach to the boys’ deaths. There was no criminal case. The lawyer filed an Ugandan civil case instead, claiming that the mothers were “deceived” because they thought they brought their children “to a professional place.” Miss Bach had worn a stethoscope around her neck and “presented herself” as a doctor. The lawsuit claimed that Miss Bach’s actions were fraud that led to deaths. Miss Kwagala felt she had a landmark case; no Ugandan had ever sued a missionary. “Our organization is raising the moral consciousness of our community to start questioning,” Miss Kwagala told her colleagues, “So now, the community’s like, ‘Oh, wait a minute! It is wrong what the white person did. You can sue.”

Renee and Lauri Bach were horrified when they were served with the complaint. It said they had “violated the . . . Applicants (sic) right to dignity and freedom from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and psychological torture . . . .” The human rights statutes cited had been written for war crimes.

Miss Bach was “so disappointed and so broken. . . . I have not denied being more involved in the medical side than I should have, but the only reason I did that was to help save someone’s life. I did not kill children.”

Miss Bach hired a lawyer, David Gibbs III, who told her the case had no merit and was “activist litigation.” He held a mediation meeting by video conference to explain that SHC’s records showed that the head nurse, Mrs. Alonyo, examined Elijah and refused to admit him because he had tuberculosis. Twalali was treated by SHC’s doctors, but Miss Bach’s passport stamps prove she was in the United States at the time. Miss Kwagala said the issue was not whether Miss Bach was present, but that she was head of the institution. Miss Bach said she felt sorry for the women who had lost their children, but she refused to pay to settle the case.

Miss Kwagala then tried to find a plaintiff who could be directly linked to Miss Bach. She found Miss Bach’s blog entry about Patricia — the child who had a reaction to a blood transfusion — and invited Patricia and her mother to a meeting, with Miss Nielsen present. The mother praised Miss Bach, saying she nursed Patricia’s wounds. When the lawyer asked if she thought Miss Bach had harmed her daughter, she said: “Oh, my God, that woman saved me and my child! She paid all the bills; took us to a very nice hospital.”

Miss Nielsen was annoyed that Patricia’s mother refused to sue. The mother said “the white woman” (Miss Nielsen) took a photo of Patricia and then they were “ordered to leave.”

No White Saviors posted the picture with the caption: “Some of #ReneeBach’s victims are still alive. This is Patricia, left permanently disfigured after a botched blood transfusion performed by Renee. She didn’t cross-match the blood, because she’s not a medical professional, child had horrible reaction & now lives with these scars.” Miss Bach had written in her blog: “After doing a search for blood around Jinja town, we found her [Patricia’s] type and it was a match!”

Miss Kwagala continued the case against Miss Bach with only the mothers of Elijah and Twalali as plaintiffs. The court date was postponed in 2019; then again in 2020 when Covid caused shutdowns in Uganda. No White Saviors ramped up its campaign, claiming “At least 300 died while Renee was practicing hands-on medical care and while SHC wasn’t properly registered.” No White Saviors’ gained more than 600,000 Instagram followers.

It made deceptive posts. For example, it cropped a photo of Miss Bach putting an IV catheter into a baby’s head to make it look like she was alone with the baby. There were actually two nurses and a doctor in the room, who had asked Miss Bach to start the IV.

Miss Kwagala said she was perplexed by Miss Nielsen’s emotional involvement in the case and had to remind her that she was not the plaintiff. Miss Nielsen handled crowdfunding and was paying Miss Kwagala’s bills.

The lawsuit came to the attention of NBC News, and other outlets picked up the story. Miss Bach became infamous; she said she was happy to wear a Covid mask, so she wouldn’t be recognized. Miss Bach and Mr. Gibbs appeared on Fox News to try to clear her name, but that didn’t stop the bad press.

Miss Nielsen told her followers that she wanted to file criminal charges against Miss Bach in the United States, and some of her American followers agreed to make calls to see if there was a case. The documentary showed a No White Saviors meeting during which Miss Nielsen spoke to her Ugandan partners over the phone, suggesting that money be raised so the dead children’s bodies could be exhumed. Miss Alaso, her Ugandan partner in No White Saviors and the other black Ugandans who were part of the organization looked disgusted. When Miss Nielsen ended the call, they said, “Bye, mzungu! Bye, Colonizer!” and laughed.

Mr. Gibbs assured Miss Bach that there was no standing for a criminal case, but Miss Bach continued to get death threats, and was worried that someone might harm her or her family. No White Saviors had criticized her for rearing her Ugandan daughter in majority-white rural Virginia. Miss Bach tearfully told the filmmakers, “The reason my Ugandan daughter spent months and months crying herself to sleep every night, and asking why she couldn’t go back to her home country is because she’s not safe to go home because of No White Saviors.”

Mr. Gibbs believed that a judge would simply dismiss the civil suit, and Miss Bach was eager to have a ruling that would salvage her reputation, but the court date kept getting pushed back, and No White Saviors was unrelenting. Mr. Gibbs told Miss Bach, “No White Saviors, they can’t let it go . . . because you have become the golden goose for them,” a source of donations, probably almost exclusively from Americans.

Miss Bach finally decided to settle. She said, “It was the social media component that really just kind of broke me.” Miss Kwagala said the mothers of Elijah and Twalali were weary of the case, too. They told her, “We don’t want to talk to those white people anymore. Please, we don’t even want to come to court.”

The settlement stated “that without admitting liability” the mothers would get $9,480 USD each. They felt the settlement was fair; what they really wanted all along was to know why their sons had died. Miss Kwagala said that although she would have loved to have had a precedent-setting case, she was not the one who lost her children.

No White Saviors bragged that two families had been paid restitution due to their work, and its follower count on Instagram jumped to 780,000. Miss Nielsen started a crowdfunding campaign so No White Saviors could open a “Revolutionary Library & Café” in Jinja. It built the café with $80,000 in donations.

Miss Nielsen’s relationship with Miss Alaso began to unravel. Miss Alaso accused Miss Nielsen of still being a white savior, and Miss Nielsen said she was the one who had done all of the work while Miss Alaso took the credit. Shortly after the café opened, Miss Alaso publicly accused Miss Nielsen of mishandling donor funds. Miss Nielsen denied it, but No White Saviors’s followers quickly turned against her, posting comments such as, “you’re a white savior gtfo [get the f**k out].”

Then Miss Alaso announced that Miss Nielsen had resigned: “This transition process will see No White Saviors being fully run by a black team. Thank you for being part of history as we break the chains of whiteness.” Followers commented that they were happy to “have shaken that colonizer past.”

Donations to SHC dried up completely, so Miss Bach called head nurse Mrs. Alonyo and told her to discharge all the children and donate all supplies to other charities. “Serving His Children has gone, in a very painful way,” Miss Bach said.

Miss Bach was never charged with a crime in Uganda or the United States, but the vitriol took a toll. She blames herself for the fact that SHC folded. She feels angry, hurt, and betrayed. “God gave me the gift of desiring to serve other people. But now I’m caused to question, is my desire to help people selfish? Is it wanting to be a savior? Or is it genuine and selfless?”

Mrs. Kramlich believes Miss Bach was malicious, and the experience changed her thinking about God and of Christianity. She said she now sees missionary work as an industry: “Organizations are now profiting from how upset you can make people feel or how guilty you can make people feel. That’s not to negate all the good things that those places also do. So, I think it’s complicated. It’s not all or nothing.”

Kelsey Nielsen was a bully who got her comeuppance, but her self-righteousness came from a belief in “anti-racism.” She tried to help Africans who then gave her the boot after she made money for them. I cannot find any record of where she is now or what she is doing. Miss Bach saved hundreds of black children from starvation, and some blacks, such as Dr. Tagoola, appreciated it. Others — Miss Alaso is typical — resent whites and were happy to believe the worst of Miss Bach and to destroy her reputation.

The No White Saviors Instagram account today has 826,000 followers. Most appear to be white women. A lot of recent posts support Palestine, although there are also posts warning that Middle Eastern entertainment often mocks blacks. In her latest video, Olivia Alaso is wearing a shirt that says, “Olivia Rises.” She says she needs $50,000 more to keep the library open. Her GoFundMe account has netted nearly $40,000.

The No White Saviors Facebook page has 33,000 followers and the same videos. There is a lot of begging for money for the library. I’m guessing Miss Alaso doesn’t want the bother of running a cafe. Posts support Palestine and denounce colonialism.

The white women in this series should have stayed home. Better to do nothing and be thought a racist than sincerely try to help Africans and be thought a “white savior.” If they want to help, they can help their own people or redirect misplaced maternal instincts and start their own families. If they can’t help helping Africans, they can do a lot worse than give money to “Olivia Rises” and let her squander it or buy coffee and books as she sees fit.