Sir Garnet Meets the Confederates, by Jared Taylor

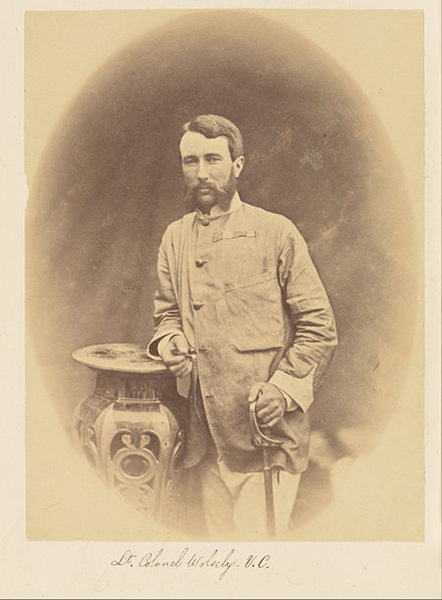

Garnet Joseph Wolseley, First Viscount Wolseley (1833–1913) was one of the most admired British generals of the age of empire. He served everywhere: Burma, India, China, West Africa, Sudan, Canada, and in the Crimean War. He achieved the rank of field marshal, the highest in the British army. Garnet Wolseley had such a reputation for order and efficiency that the phrase “Everything is all Sir Garnet” meant everything is in perfect order.

Wolseley was fascinated by the American civil war and was an official observer from September 1862 until Lee’s surrender in April 1865. He crossed several times between Union and Confederate lines, studied the tactics of both armies, and met many high-ranking officers, North and South.

As a soldier, he admired both sides: “I feel that both parties in the war have so much to be proud of, that both can afford to hear what impartial Englishmen or foreigners have to say about it.” He believed, first of all, that the war was a tragedy — that neither side was in the wrong. The tragedy was all the greater because the men who were slaughtering each were practically his kinfolk — fellow “Anglo-Saxons” who, he believed, were of the first rank among men.

In 1877, he published this in both London and New York:

I can see, in the dogged determination of the North persevered in to the end through years of recurring failure, the spirit for which the men of Britain have always been remarkable. It is a virtue to which the United States owed its birth in the last century, and its preservation in 1865. It is the quality to which the Anglo-Saxon race is most indebted for its great position in the world. On the other hand, I can recognise the chivalrous valour of those gallant men who fought not only for fatherland and in defence of home but for those rights most prized by free men. Washington’s stalwart soldiers were styled rebels by our king and his ministers, and in like manner the men who wore the grey uniform of the Southern Confederacy were denounced as rebels from the banks of the Potomac . . . . [I found Confederates to be] well versed as all Americans are in the history of their forefathers’ struggle against King George the Third, and believing firmly in the justice of their cause, saw the same virtue in one rebellion that was to be found in the other.

In an 1892 essay, he wrote:

The history of both armies abounds in gallant and chivalrous deeds done by men who fought for their respective convictions and from a sincere love of country. If ever England has to fight for her existence, may the same spirit pervade all classes here as that which influenced the men of the United States, both North and South. . . .

The South was humbled and beaten by its own flesh and blood in the North, and it is difficult to know which to admire most, the good sense with which the result was accepted in the so-called Confederate States, or the wise magnanimity displayed by the victors.

What foreigner today would write so admiringly of Americans?

Wolseley did not like slavery; he was a loyal servant of an empire that abolished slavery in 1833. However, for the Confederacy, he felt a typically British sympathy for the underdog:

As the heroic struggle of a small population that was cut off from all outside help against a great, populous and very rich Republic with every market in the world open to it and to whom all Europe was a recruiting ground, this Secession war stands out prominently in the history of the world.

Also, although Wolseley respected Union commanders, he thought the Confederates were superior men. Robert E. Lee stood apart:

I have met many of the great men of my time, but Lee alone impressed me with the feeling that I was in the presence of a man who was cast in a grander mould, and made of different and of finer metal than all other men. He is stamped upon my memory as a being apart and superior to all others in every way: a man with whom none I ever knew, and very few of whom I have read, are worthy to be classed.

How often have men, eminent in their own right, ever spoken so reverently of a contemporary? He wrote of Lee’s “calm self-possessed dignity, the like of which I have never seen in other men,” and concluded:

It would be difficult to find in history a great man, be he soldier or statesman, with a character so irreproachable throughout his whole life as that which in boyhood, youth, manhood, and to his death, distinguished Robert Lee from all contemporaries.

Wolseley was born into an ancient, landed family and his father was a major in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. He believed a modern army needed high-born, professionally trained commanders, but Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest forced him to set aside his prejudices:

Forrest had fought like a knight-errant for the cause he believed to be that of justice and right. No man who drew the sword for his country in that fratricidal struggle deserved better of her; and as long as the chivalrous deeds of her sons find poets to describe them and fair women to sing of them, the name of this gallant, though lowborn and uneducated general, will be remembered by every Southern State with affection and sincere admiration. A man with such a record needs no ancestry, and his history proves that a general with such a heart and such a military genius as he possessed, can win battles without education.

His military career teaches us that the genius which makes men great soldiers is not to be measured by any competitive examination in the science or art of war, much less in the ordinary subjects comprised in the education of a gentleman. . . . ‘In war,’ said Napoleon, ‘men are nothing; a man is everything.’ And it would be difficult to find a stronger corroboration of this maxim than is to be found in the history of General Forrest’s operations.

Wolseley was likewise awed by Stonewall Jackson. When Wolseley’s friend, the British military historian Colonel George F. R. Henderson, published a biography of Jackson in 1898, Wolseley wrote the introduction. Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War is Henderson’s masterpiece. It is still in print and highly regarded. Wolseley wrote:

The most reckless and irreligious of the Confederate soldiers were silent in his [Jackson’s] presence, and stood awestruck and abashed before this great God-fearing man; and even in the far-off Northern States the hatred of the formidable ‘rebel’ was tempered by an irrepressible admiration of his piety, his sincerity, and his resolution. The passions then naturally excited have now calmed down, and are remembered no more by a reunited and chivalrous nation. With that innate love of virtue and real worth which has always distinguished the American people, there has long been growing up, even among those who were the fiercest foes of the South, a feeling of love and reverence for the memory of this great and true-hearted man of war, who fell in what he firmly believed to be a sacred cause. The fame of Stonewall Jackson is no longer the exclusive property of Virginia and the South; it has become the birthright of every man privileged to call himself an American.

Like Wolseley, Colonel Henderson admired both sides, and felt he was almost writing the story of his own people:

While compiling these pages I have always borne in mind the words of General Grant: ‘I would like to see truthful history written. Such history will do full credit to the courage, endurance and ability of the American citizen, no matter what section he hailed from, or in what ranks he fought.’ I am very strongly of the opinion that any fair-minded man may feel equal sympathy with both Federal and Confederate. Both were so absolutely convinced that their cause was just, that it is impossible to conceive either Northerner or Southerner acting otherwise than he did. . . . It is with those Northerners who would have allowed the Union to be broken, and with those Southerners who would have tamely surrendered their heredity rights, that no Englishman would be willing to claim kinship. [Wolseley: G. F. R. Henderson, Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War, Longmans, Green, and Co, 1911, Volume I, p. viiif.]

Henderson saw the Virginian as an inspiration for all English-speaking white men:

In whatever fashion his own countrymen may deal with the problems of the future, the story of Stonewall Jackson will tell them in what spirit they should be faced. Nor has that story a message for America alone. The hero who lies buried at Lexington, in the Valley of Virginia, belongs to a race that is not confined to a single continent; and to those who speak the same tongue, and in whose veins the same blood flows, his words come home like an echo of all that is noblest in their history: ‘What is life without honour? Degradation is worse than death. . . .’ [Henderson, Vol II p. 497.]

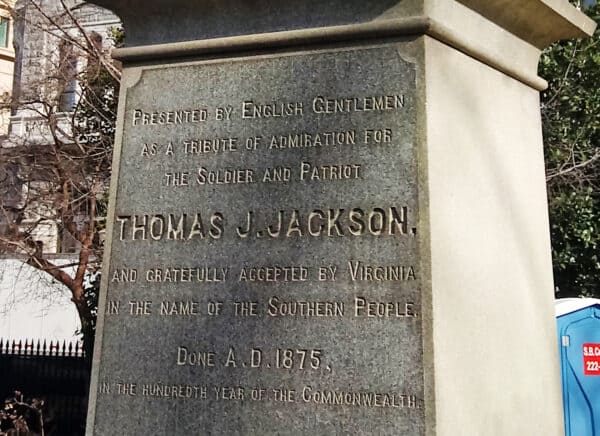

Many Englishmen admired the Confederates. There still stands a statue of Stonewall Jackson on the grounds of the Virginia statehouse in Richmond.

On the pedestal are inscribed these words: “Presented by English gentlemen as a tribute of admiration for the Soldier and Patriot Thomas J. Jackson.”

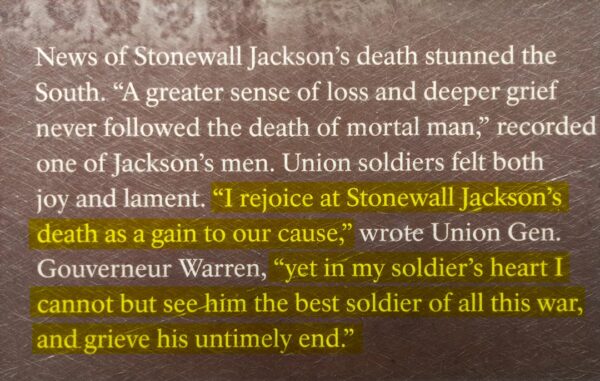

The very men Confederates were trying kill could not help honoring them. On hearing the news that Jackson had been killed at Chancellorsville, Union General Gouverneur Warren wrote, “I rejoice at Stonewall Jackson’s death as a gain to our cause, yet in my soldier’s heart I cannot but see him the best soldier of all this war, and grieve his untimely end.”

Twenty years after Appomattox, Wolseley made this prediction:

[W]hen Americans can review the history of their last great rebellion with calm impartiality, I believe all will admit that General Lee towered far above all men on either side in that struggle: I believe he will be regarded not only as the most prominent figure of the Confederacy, but as the great American of the nineteenth century, whose statue is well worthy to stand on an equal pedestal with that of Washington, and whose memory is equally worthy to be enshrined in the hearts of all his countrymen.

For 80 years, that prediction seemed to be coming true. In 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower — a Kansas boy — explained why he hung a portrait of Lee in the Oval Office:

General Robert E. Lee was, in my estimation, one of the supremely gifted men produced by our Nation. . . . [H]e was thoughtful yet demanding of his officers and men, forbearing with captured enemies but ingenious, unrelenting and personally courageous in battle, and never disheartened by a reverse or obstacle. Through all his many trials, he remained selfless almost to a fault and unfailing in his faith in God. Taken altogether, he was noble as a leader and as a man, and unsullied as I read in the pages of our history.

[A] nation of men of Lee’s calibre would be unconquerable in spirit and soul. Indeed, to the degree that present-day American youth will strive to emulate his rare qualities, including his devotion to this land as revealed in his painstaking efforts to help heal the Nation’s wounds once the bitter struggle was over, we, in our own time of danger in a divided world, will be strengthened and our love of freedom sustained.

This was a common view. During the first half of the 20th century, the United States Army named 10 military bases for Confederate generals (all recently renamed for blacks, women, etc.)

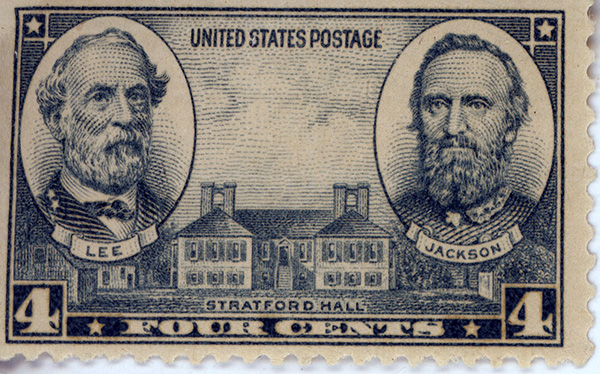

In 1937, the postal service issued this commemorative stamp of Lee’s boyhood home, Stratford Hall, with images of Jackson and Lee. The stamp was part of a series of five stamps, issued under the direction of Franklin Roosevelt, honoring American military heroes. Its color is Confederate gray.

During the Second World War, there was a tank named after the Confederate cavalry commander Jeb Stuart.

There were also Grant and Lee tanks, Grant on the left, Lee on the right.

In 1955, a Lee stamp was issued as part of the “liberty series” that included Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, and Lincoln — all symbols of American liberty.

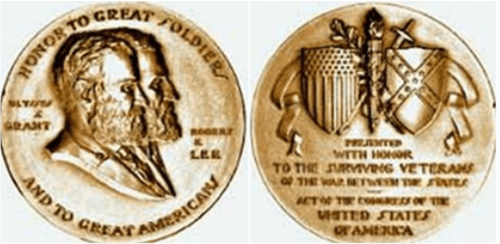

In 1956, Congress awarded the Congressional Gold Medal — the highest honor Congress can confer — on all living Civil War veterans, Union and Confederate alike.

On the front were Lee and Grant, with the words, “Honor to Great Soldiers and to Great Americans.” On the back were shields with insignia of both sides.

In 1957, Hollywood produced a television series called “The Grey Ghost,” based on the life of Confederate Major John Singleton Mosby. He is the hero, outwitting Yankees, always chivalrous.

What happened to this willingness to honor bravery and dedication on both sides? The short answer — and the long answer — is race. Race has turned the history of the United States inside out. The story of America used to be a heroic saga, beginning with Columbus bringing Christianity and civilization to the New World. Jamestown, Plymouth Colony, the Revolution, the conquest of a continent, the emergence of an economic and military superpower — all were glorious achievements, mainly by men Wolseley and Henderson would have called fellow Anglo-Saxons.

Now, those Anglo-Saxons have been unmasked as slave drivers and murderers, and the United States as nothing more than a white-supremacist crime scene. Confederates, no matter how fine their qualities, are the vilest of all white criminals because they fought for a nation that wanted to preserve slavery. This is why men not fit to lace Robert E. Lee’s boots ransack and tear down his monuments.

Like so many humiliations, this one has been forced on us from above. A 2017 Reuters poll found that 54 percent of all Americans — including immigrants and non-whites — thought Confederate monuments should be left standing; only 27 percent thought they should be taken down. A 2022 Quinnipiac poll — in a live telephone interview in which people might be afraid to tell the truth — found that 50 percent said the monuments should remain and 39 percent wanted them taken down. In a poll that broke respondents out by race, even blacks supported removal by only a small majority — 44 percent to 40 percent — while two-thirds and whites and Hispanics thought they should stay.

Much of the campaign of hatred against the Confederacy has been led by elites who can be called white only as a courtesy, and by blacks. The more blacks gain in status, wealth, and power, the more they seem to resent whites. It’s no coincidence that what some consider the most beautiful public monument in America was torn down in a black-run, black majority city.

It’s no coincidence that the defense secretary that gave the order for the entire US military to remove “all names, symbols, displays, monuments, and paraphernalia that honor or commemorate the Confederacy” was a black man, Lloyd Austin. This included no fewer than 750 acts of obliteration, including base names, street names, names of ships, and even artworks at West Point and the Naval academy. It is hard to think of a more ruthless repudiation of a tradition that Congress, the postal service, and even Hollywood admired as recently as the 1950s.

It’s no coincidence that as Andrea Douglas of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center who watched the destruction of the Charlottesville Lee statue, said, “It feels like witnessing a public execution.” The last public execution in the United States was 88 years ago, but Dr. Douglass thought this a fitting end to the man Eisenhower called a man as “unsullied as I read in the pages of our history.” She probably doesn’t know what Eisenhower thought about Lee, but she probably wouldn’t care. Eisenhower was a white man and therefore of the same criminal class as Lee and, no doubt, Viscount Wolseley.

It’s trite to note that if Lee deserves a public execution so does George Washington. He was also a slaveholder who went to war against established authority. As with Lee, this is all we need to know about him to despise him.

As the polling data noted earlier shows, “our democracy” ignores the desires of Americans when they are not what our rulers think they should be. I cannot therefore imagine a restoration of white American self-respect at the national level. If this is a land in which Europeans expect to live in anything other than increasing humiliation, they will have to find local solutions, carve out havens in which their children can grow up without being told that they, their history, and their heritage are dirt.

We can expect no help from the descendants of Viscount Wolseley, Col. Henderson, and the English gentlemen who so admired a foreign soldier that they paid to erect his statue thousands of miles away. They and the society that bred them are as extinct as the Confederacy. We can look only to ourselves and try to live by the rules Lee and Jackson set for themselves:

“Duty is the sublimest word in the language; you can never do more than your duty; you shall never wish to do less.”

“What is life without honor? Degradation is worse than death. We must think of the living and of those who are to come after us, and see that by God’s blessing we transmit to them the freedom we have ourselves inherited.”