The Maidan Cookie Has Crumbled, by John Helmer

All’s fair in love and war – this is a 500-year old English proverb but it isn’t in the Geneva conventions on war crimes and genocide, much as the US and US-backed Israel claim it is.

In the war of US, NATO and their Asian allies against Russia, it is turning out that almost all the major companies on the enemy side love Russia too much to leave.

They also think Russia has won the war, so they are convinced — the executive managers, boards of directors, control shareholders, and bankers — that there is no point in leaving. So they continue to do business in the Russian market profitably, while they wait for the military defeat of the Ukraine and their own governments to register, and the terms of capitulation allow them to tell their shareholders, “we told you so.”

That notice will be delivered with a dividend paid out of the profits the companies continue to earn from their Russian businesses. The shareholders will be satisfied with both; they will vote their confidence, with a bonus, for the chief executive and board at the next Annual General Meeting.

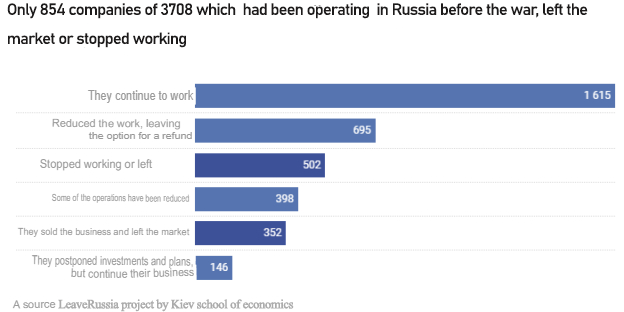

Two studies on the enemy side, one by the Kiev School of Economy’s (KSE) “Leave Russia” and “SelfSanctions” projects, and a follow-up by the Russian-language publication Novaya Gazeta Europa have reported results of their surveys of 110 international firms working in Russia. This is fresh evidence of the defeat of the enemy in the economic war — from the foxhole of the enemy.

The survey results demonstrate that after two years of intense pressure and threat campaigns by the US, NATO and the Ukraine for the companies to wind up their Russian businesses and leave Russia, the outcome is defeat.

KSE claims this work has been done by “a team of Ukrainian IT volunteers;” the Yale University’s School of Management collaborated with data on the companies. Volunteer doesn’t mean what it seems in Ukrainian. The funding for the operation has come through KSE’s money suppliers, which include several Ukrainian ministries, whose funding comes in turn from the International Monetary Fund, the US, and the European Union (EU). “KSE Institute’s clients”, the institution’s website says of its paymasters, “also include the American Chamber of Commerce in Ukraine, the European Business Association, and a number of large law and development companies. Among the international partner organizations are USAID, UK aid, DFID, the embassies of the United States, Canada and the Netherlands, the EBRD, the World Bank, the EU Commission, IFC, WHO, UNDP, GIZ, UNICEF, Yale School of Management and others.”

KSE’s “SelfSanctions” project is paid for by another group of “partners” including George Soros, government-backed organizations in Germany, Norway, Taiwan, and Poland, and a Ukrainian entity called “Squeezing Putin”. This takes US and other intelligence material, feeds it to the Anglo-American media, and then identifies the media reports as corroboration of the process for sanctioning companies which remain in Russia and are attacked in the press as an “international sponsor of war”.

KS adds a note of self-importance: “Kyiv School of Economics holds the first place among the most powerful economic analytical institutions of Ukraine according to the RePEc rating.”

The importance, the breaking news, is that, according to the newly published evidence, 82.7% of the international companies surveyed have dismissed KSE, its foreign state financiers, and its economic warfare projects as a failure – and their shareholders concur.

This is how the Maidan cookie crumbles.

The Russian report by Novaya Gazeta Europa, officially identified by the Russian government media monitor as a foreign agent, was published on February 6. It appears on the Russian website of the publication; not on its English website. The publication attaches this notice: “Military censorship has been introduced in Russia. Independent journalism is banned. We continue to work because we know that our readers remain free people. Novaya Gazeta Europa reports only to you and depends only on you. Help us to remain the antidote to dictatorship – support us with money.”

Unlike the international companies it is reporting on, Novaya Gazeta Europa has left Russia, and is based in Riga, Latvia.

A summary report of the same material appeared on the same day in The Bell. This is also a foreign agent publication; since 2019 it is reportedly financed by the oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov; follow his business practices here. Prokhorov has become an Israeli citizen and lives in that country.

The Russian text has been translated verbatim; illustrations have been added for clarification.

“If you work quietly, no one will come for you” — we have studied the cases of 110 foreign companies doing business in Russia despite the war. That’s why they never left.

By Denis Morozhin

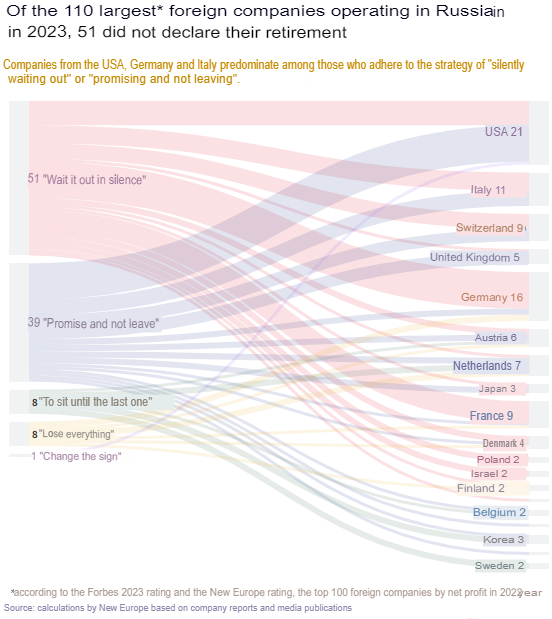

The Russian authorities like to talk about how foreign companies only pretend to leave Russia, and if they do leave, they will certainly return. As the Novaya-Europa study shows, foreign business gives the Kremlin reasons for such statements. Of the 110 largest foreign companies which continue to operate in Russia, 51 were not even going to leave, and another 40 changed their minds or were unable to sell their assets at a bargain price. We tell you about the five main strategies that allow them to stay in the country during the war.

Shortly after February 24, four global tobacco giants that divided the Russian market among themselves — Japan Tobacco, Philip Morris, British American Tobacco and Imperial Brands — made the most radical statements about working in Russia: ‘We will leave the country, we will sell the business.’ Back in 2022, the sources of Novaya Europa assessed these plans extremely skeptically. “At least the largest tobacco companies will definitely not leave, why would they do that? Do you think that if Philip Morris does not close the factory near St. Petersburg, people in Indonesia or Brazil will stop buying Marlboros to take revenge on those who sold themselves to Putin and pay taxes for the war?” one of the insiders of this market said at the time.

Almost two years after the outbreak of a full-scale war, it turned out that this forecast has largely come true. Not only tobacco companies (of which only British American Tobacco and Imperial Brands have left), but also many other major companies continue to work in Russia despite all their promises and even despite the title of ‘sponsors of war’ assigned to them in Ukraine. It was the market leader, Japan Tobacco, who explained the continuation of work at the end of 2023 as follows: we do not want to “deprive consumers of the product they are used to.” At the same time, according to Novaya-Europa, back in the summer of 2022, this manufacturer was negotiating a sale, and its corporate statements confirmed this.

By the beginning of 2024, it became clear: some do not leave, because they know that if they anger the Russian authorities even a little bit, they will lose key assets and a lot of money. The second is just fine in Russia, they have no reason to lose a profitable business, and now they have even stopped hiding it — although they promised to leave the market. Still others, whose example is certain warning for others, did not want to come out on the Kremlin’s terms, went into conflict with the authorities — and lost everything. The fourth, looking at the first three groups, just remain silent and work quietly all these two years.

Source: https://novayagazeta.eu/

Novaya Gazeta Europa studied the cases of 110 foreign companies which either worked in Russia in 2023 or left the market no later than the second half of 2023. We took the 50 largest foreign companies according to the Forbes 2023 rating and added to them firms from the Novaya Europa rating compiled last year of the top 100 foreign companies by net profit in Russia in 2022 (minus those who completed their exit from the country before July 2023).

It has turned out that these companies can be divided into five categories depending on their operating strategies in Russia.

We have called the largest group, which included 51 companies, “Wait it out in silence.” At best, they have expressed concern about the outbreak of a full-scale war, or they have simply remained silent. Some of them have explicitly said that they would continue to work. Among those who still adhere to this model of behaviour are Auchan, Metro, Calzedonia, Ecco, Benetton, Ehrmann, TotalEnergies, Rockwool, Mitsui, and major pharmaceutical companies.

According to our calculations, in 2022 – the reports for 2023 have not yet been published — they have received a total net profit of 448 billion rubles.

The second largest group, in which we included 40 firms, are those which promised to sell their business, leave the market, reduce investments and abandon development plans in Russia – this is the “Promise and not leave” strategy. As a result, they retained a variety of assets in the country: production, retail chains, brands, service or supplies. Examples include BP, JTI, PMI, Pepsico, Mars, Nestle, Raiffeisen, UniCredit, Intesa, ABB, Bacardi, Campari. This group is smaller in number, but larger in total profit — 669.6 billion rubles. We have identified three companies in a separate group (Leroy Merlin, Decathlon, Adidas) which have retained their brands in Russia on one condition or another — in fact, they “left without leaving.” All of these companies did not disclose profits for 2022.

Two small groups, in each of which we have included 8 companies, have adopted the strategies of “Sitting until the last” and “Losing everything”. Those who stayed (with a total profit of 43 billion rubles) promised to leave the market, but sold the business only in the second half of 2023, usually at a discount and on unfavourable terms. These are Hyundai, Kia, Volvo, Ingka Group (shopping centre investor), AB InBev, Veon.

The same number also went into confiscation or external management because they quarrelled with the Russian authorities or became, according to the Kremlin, a “compensation fund” – held for potential offset if the West fails to compensate for its seizure of Russian assets abroad — Danone, Carlsberg, Fortum and others with a total net profit of 48.8 billion rubles.

According to the calculations of Novaya-Europa, the leaders in choosing the first two strategies, which involve maintaining business in Russia, are companies from the United States, a total of 20 of them. Germany is in second place with 14 firms (12 of them are “silently waiting it out”), Italy is in third place with 11.

Source: https://novayagazeta.eu/

The strategy of “sitting it out and keeping business” shows that foreign companies have verbally condemned the war. In fact, however, it is more important for them to preserve the opportunity to earn in a large and growing market. These earnings probably outweigh the potential problems in Western consumer markets for them. It is in order to create such difficulties for companies that the Ukrainian authorities have created a register of “International Sponsors of War”, which at the end of January includes 48 companies (31 of them from countries that the Russian authorities call “unfriendly”).

Since mid-2023, some companies on this list have begun to face corporate boycotts in the West. However, this has turned out to be very localized and has so far mainly manifested itself in the Scandinavian countries. For example, Swedish SAS has decided to stop feeding passengers with Mondelez and Nestle products, as well as drinking Pepsico soda and Bacardi alcohol.

Other consumers in Sweden and Norway, in particular, the railway company, the ferry carrier Tallink and others, began to refuse Mondelez chocolate. “At the same time, Mondelez is holding up for now,” a Russian lawyer who specializes in international trade said in a conversation with Novaya—Europa. In Finland, the VR rail carrier and Finnair airline have said they may reject Nestle and Unilever products.

Ukraine has included all these companies in the list of sponsors of the war, but it is still difficult to judge the economic consequences of the boycotts, because they began very recently. None of the companies has yet claimed damage from these measures.

Hostages and “calculating men”

Many companies found themselves in the position of hostages of the Kremlin, and these are both those who promised to leave Russia, but did not do so, and those who remained silent for two years, say the sources of Novaya Europa. “They are forced to work in Russia and have become an offset fund which the Russian authorities need to exchange for Russian assets blocked abroad,” an expert from one of the major analytical companies believes.

He explains the status of “hostages” by the mass of restrictions imposed on foreign firms, which deprive them of the chance to exit without serious losses for the business. In particular, bankruptcy is prohibited, and if there are signs of premeditated bankruptcy, then managers face criminal liability.

Assets can be sold at a discount of 50% of their current estimated value, which is now very low. And most importantly, you need to get a sale transaction permit through a special commission, which reviews and agrees to an average of one or two transactions per month, the expert notes.

Among the global giants who tried, but could not sell their factories in Russia on favourable terms, but did not want to lose everything, the experts identify Mitsubishi Motors, ABB, General Electric — all of them have stopped production in Russia.

But there is also a directly opposite group — the “calculating ones” who understand perfectly well that their position in the market is such that they can safely continue working in Russia. If the Kremlin takes their assets to bargain with the West, it will cause problems for the economy.

Despite the fact that the state, after the outbreak of a full-scale war, has learned to take away private business from owners, the authorities simply cannot nationalize some companies, otherwise that will be a “shot in the foot,” our sources say. Tobacco concerns are an example of this, according to our industry sources. Of the four largest cigarette manufacturers represented in Russia, Russian assets have been sold to British American Tobacco and Imperial Brands, while Japan Tobacco and Philip Morris are in no hurry.

“Let’s imagine that Putin took Russian factories from Japan Tobacco and Philip Morris, just as he confiscated the assets of Carlsberg and Danone. And then it is possible that factories in Russia will have serious problems with the supply of raw materials. Tobacco plantations, of course, do not belong to cigarette manufacturers. But global concerns still know how to interact with plantation owners who can meet the global giants halfway and arrange problems with the supply of tobacco raw materials to Russia,” says a source of Novaya-Europa, who knows this industry well.

At the same time, he adds, tobacco raw materials are produced, among other countries, in China: “But there is another tobacco, though it is not very suitable for our factories. And China, even though it is our friend, will also not want to quarrel with the West. And what happens when cigarettes run out in the stores, Putin and his friends should remember perfectly well, because in 1990 and 1991, because of such a shortage, people blocked Nevsky Prospekt in the president’s hometown”. Anatoly Chubais recalled such a riot – there was similar unrest in Moscow and other cities.

The Russian market for worldwide global tobacco manufacturers is at least number two in global size, so it cannot be lost, says another source in the industry. “They want to sit here until the last moment and earn money”, he thinks. For example, Japan Tobacco earned a fifth of its $3 billion in net profit for 2022 — or $645 million — in Russia (43.5 billion rubles, recalculated at the average ruble exchange rate of 67.46 to the dollar). At the same time, its ruble profit in Russia in 2022 increased by one and a half times compared to 2021.

At the same time, Philip Morris earned $787 million (53.1 billion rubles) in Russia in 2022 — about 5.4% of its total net profit of $9.05 billion in the same year. Its Russian net profit increased by a third in the first year of the war.

Stand with a drink replacing Coca-Cola at a grocery store in Moscow, June 10, 2022. After Coca-Cola announced the termination of its business in Russia, the new product has already appeared on the shelves of Moscow supermarkets. Bela Cola, produced in Belarus, was previously available only in some regions of Russia. It is reported that since February 2022, imports of carbonated beverages to Russia have increased by 50 percent. Photo by Vlad Karkov / SOPA Images / LightRocket / Getty Images

Promising does not mean leaving

Among those who spoke about their intentions to leave the market, but have remained while only partially reducing their presence, there are many global producers of what you can eat and drink. These include both of the world’s main suppliers of non-alcoholic soda, as well as both of the largest alcohol sellers, Bacardi and Campari Group.

It is noteworthy that all these companies (as well as Mars, Nestle, Procter& Gamble, Mondelez and others) have behaved in approximately the same way. In the early days of the war, they issued fairly similar statements about the suspension of some operations in Russia (Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Campari).

Source: https://contact.pepsico.com/

By the beginning of the third year of the war, in reality there their business has been preserved. Coca-Cola and PepsiCo have left their production facilities in Russia and are making money on local brands, removing the global brands from the market. Campari has only slightly reduced its sales in Russia (according to Kommersant, through its Russian subsidiary in January–July 2023, this concern imported 3.12 million litres of alcohol against 3.58 million litres a year earlier).

A most interesting thing has happened with Bacardi: immediately after the outbreak of the war, the world’s largest family-owned alcohol company announced that supplies to Russia had been stopped and investments had been frozen. But in August 2023, The Wall Street Journal drew attention to the fact that these promises had disappeared from the statement on the company’s website. Bacardi not only kept supplies, but also continued to pour William Lawson’s whiskey in Russia.

“They are a non-public company, and they can afford to say that if there is no direct ban, then all this does not concern them. The fact that Bacardi’s headquarters are located in Bermuda helps them behave this way, and they can always say: ‘We are not an American company and we decide who we work with.’ Although in other situations they may associate themselves with the United States, where they have a large division,” said a source in the alcohol industry. Bacardi, as well as Campari, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo did not respond to questions for this article.

The predominantly American businesses have turned out to be much more cynical about the war, says Ivan Fedyakov, CEO of the INFOLine analytical agency. “European companies are afraid of a consumer boycott, which can cause significant damage to business. For Americans, the conflict with Ukraine is far away from them,” he says. If the conflict flares up more sharply, then American companies may remember that they pay taxes in Russia, but for now they are waiting for the pendulum to swing in whatever direction, the expert argues.

Another striking example of such a strategy is the Austrian Raiffeisen Bank. At the beginning of the full-scale war, the bank, like dozens of companies, published a cautious statement — this has now been deleted from the bank’s website, but has remained in the Wayback archive — about leaving Russia “under strict control.” After that, the bank repeatedly told the public about various exit strategies, including the separation or sale of the business, but repeatedly postponed the date for a possible transaction. However, as Reuters wrote at the end of 2023, citing Austrian officials, Austria itself is not interested in this: the government does not want to completely cut off relations with Moscow, because it still hopes for their resumption. And besides, Vienna wants to remain a “hub for money” that goes between Russia and Eastern Europe, Reuters concluded.

“Raiffeisen hopes that a possible change in the geopolitical situation will allow it to stay and work as before,” a member of the board of one of the Russian banks told Novaya-Europa. At the same time, the Russian business, according to the results for the first nine months of 2023, brought the Austrian bank half of its global profit (1.024 billion euros out of 2.114 billion euros). If you try to leave Russia without the consent of the authorities, then “you can only write everything off to zero, and also face arrest,” a source of Novaya-Europa in Western banking circles is sure.

At the same time, Raiffeisen is a systemically important bank in Austria — it holds the first place in terms of assets and a market share of 17%. The Austrian authorities would be forced to support such a financial institution if it has problems. And the loss of a huge business in Russia is quite capable of triggering such hypothetical difficulties, our banking source argues. It is unlikely that the Austrian authorities want to solve the problem of recapitalization of the giant bank.

Work and keep quiet

“We have a cynical opinion in the industry that the main reason is revenue. The Russian market may account for even a small share of their income, but in absolute numbers it’s still a lot of money,” explains the strategy of a manager of one of the largest food companies in Russia. “And if you work quietly, then no one will come for you,” says the source. He cites another reason why companies are “working quietly” without talking aloud about an exit: “The risk of asset loss. The illustrative cases are known; if the business is selected [by the authorities to make an example for others], then no one will help.”

Among those who chose the “work and keep quiet” strategy, the most notable are the giant retail chains: German Metro, French Auchan, as well as the Leroy Merlin network, presumably related to Auchan (both of them, as well as the Decathlon network, are owned by the French family company Mulliez). Auchan, Leroy Merlin and some other European companies are in no hurry, because for them leaving the Russian market will be more painful than a possible boycott or public opinion, says one of the industry sources.

Left: one of the LeRoy Merlin stores in Russia; right, Gérard Mulliez, patriarch of the family owning LeRoy Merlin, Auchan, Decathlon and other retail chains operating in Russia.

In December 2023, the data of the Unified State Register of Legal Entities showed that the owner of Leroy Merlin had changed: it became the company Scenari Holding LP from the United Arab Emirates. The market does not believe this. One of our industry sources, who asked not to be named, believes that in fact the French owners could have retained control of the network. He explains this by saying that Leroy Merlin, with 112 hypermarkets in Russia, which tops the Russian Forbes ranking of foreign companies by revenue, is too large an asset to be sold to an unknown company. The source recalls that until 2022, Leroy Merlin had more than a quarter of its revenue generated in Russia; losing that would mean dealing a severe blow to the business.

Two more examples of “changing signage” are Decathlon and Adidas. The first one sold its chain to the Russian company ARM (previously it specialized in the restaurant business), which opened stores under the name Desport. They sell products of the same brands as in the “old” Decathlon — the Desport online catalogue confirms this.

Adidas exited very cleverly. It subleased some of its stores to Lamoda, retaining its legal entity in Russia, and now sells its products through an official Russian distributor.

The illusion of return for energy production

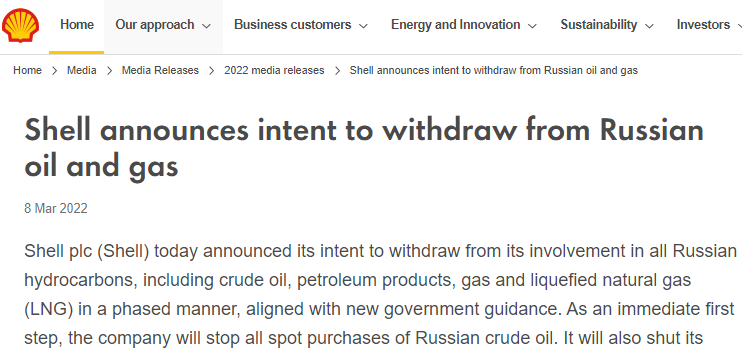

The Kremlin has managed to show foreign companies that those who insist on their rights will lose everything. In particular, Shell, an oil and gas producer, and Carlsberg, a brewer, have faced this. The result is that only the one who knows how to negotiate retains assets or is allowed to leave Russia with money. Other companies from the same industries, oil and gas and beer, have succeeded: BP, TotalEnergies and Heineken.

Shell has been producing and liquefying gas on Sakhalin for 15 years and selling liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Asian markets, mainly to neighbouring Japan. Then a full-scale war broke out – and the concern, which had been friends with the Kremlin for decades, was one of the first to announce that it would withdraw from all enterprises in Russia. Moreover, it did this without equivocation, issuing a harsh statement on the fourth day of the invasion of Ukraine, on February 28, 2022.

Source: https://www.shell.com/ — March 8, 2022

Perhaps that is why Vladimir Putin by his decree dated June 30, 2022, effectively took away 27.5% of the LNG plant on Sakhalin from Shell. Formally speaking, according to this decree, the Kremlin took the plant from all its shareholders, including Gazprom (50%), Japanese Mitsui (12.5%) and Mitsubishi (10%) – the latter are representatives of the “sit and wait” strategy — and transferred the enterprise to a specially created Russian company, Sakhalin Energy. Of course, the Japanese and Gazprom agreed to become its shareholders. Shell refused this honour.

The refusal of the Anglo-Dutch company meant that, according to the same presidential decree, Shell’s share had to be sold, and the money blocked inside Russia in a Type C account. In the spring of 2023, the Russian government allowed Novatek to buy this block of shares. Novatek is the second gas producer in Russia after Gazprom and the Kremlin’s great hope for conquering the global LNG market. Its export is critically important for the budget of Russia, which is under an oil embargo due to the war.

In the spring of 2023, Kommersant reported that Novatek co-owner Leonid Mikhelson (right) asked Putin to allow Shell to withdraw $1.16 billion from Russia for the sale of the stake in the Sakhalin plant – and Putin, according to the newspaper, gave such consent. The deal is still in limbo and probably not completed, two sources in the oil and gas market told Novaya-Europa: they say they do not know whether Novatek will receive the share and Shell will receive the money. “In fact, [Shell] hasn’t left”, one of the sources said. One of the proofs of this, he believes, is that the stock quotes of Novatek “have not yet gained value on the entry into Sakhalin-2 in any way.” In the database of Spark legal entities, information about the shareholders of Sakhalin Energy is classified.

When asked by Novaya-Europa whether the company received money for the asset, Shell’s press office noted that they have nothing to add to what is written about this in the “Frequently Asked Questions” section on the company’s website. This says: “We reserve all our legal rights in relation to our share of 27.5% (minus one share) in the Sakhalin Energy Investment Company.” That is to say, the share in the very company from which Putin took the plant last year.

One of our sources in the oil and gas market believes that this statement of the company can be interpreted as follows: Shell considers the nationalization illegal and may well sue the Kremlin to protect its rights to the asset. At the same time, in December 2023, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak did not confirm that the Shell and Novatek deal had been completed.

But Shell’s competitors, British BP and French TotalEnergies, did not issue loud statements and did not promise to protect their shareholder rights. And as a result, they have retained their assets in Russia. TotalEnergies’ strategy is to continue making money from LNG production together with Novatek, in which it owns a 19.4% stake. In addition, the French concern owns stakes in Arctic gas projects jointly with Novatek.

Total’s map of its joint Arctic gas projects with Novatek, 2018

BP has carefully assured the public that “we continue to consider options for completing our exit.” At the same time, the company is well aware that it cannot sell 19.75% of its Rosneft shares due to the restrictions imposed in Russia. “It does not count on the imminent end of the war and normalization of relations, and therefore it does not think to sit it out”, a former manager of the oil company familiar with the situation told Novaya-Europa; he asked not to be named. In this situation, all BP could do has been to limit itself to “honest deconsolidation – it does not show this asset in the financial reports, displaying the subtraction from the point of view of the market. This is why its production, reserves, cash flows all fell,” he added. BP did not respond to a request for comment.

“Our business was stolen in Russia”

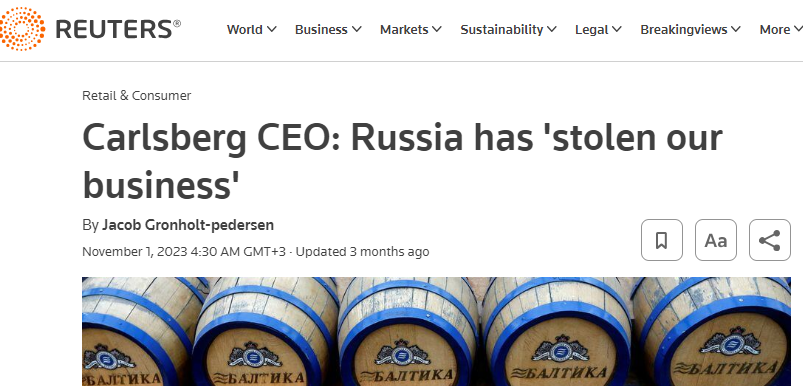

In the beer industry, there are also both nonconformists and skilful diplomats. The second obviously includes Heineken, which, according to our source in this market, “came to the authorities and said that the company was ready to leave on your terms, but with some money, bring your buyer, they say — the main point was that he was neutral and not under sanctions.” As a result, it was bought by the Russian concern Arnest, which in September 2022 bought three Russian factories for the production of aluminum cans from the American Ball Corporation.

Carlsberg, our source claims, was not ready to accept such conditions, and wanted to choose a buyer itself, and “from the point of view of the government behaved unconstructively.” As a result, Heineken earned at least a little on leaving: Arnest repaid the debt of its Russian subsidiary for €100 million. However, Baltika, owned by Carlsberg, came under the external control of the state. In response, the Danish concern stated that “our business was stolen in Russia.”

Source: https://www.reuters.com/

“Now, if this situation can be resolved, it is only at the level of heads of state and interstate negotiations. And since they are impossible now, it seems that Carlsberg will have to forget about the Russian asset,” says our source in the industry. At the same time, according to his information, Arnest was ready to buy the Russian business of both brewing companies (and Carlsberg in June 2023 even managed, without specifying the buyer, to announce that it had already signed an agreement on the sale of the business), but did not receive the Kremlin’s consent to Baltika.

Denmark’s share of total Russian assets frozen or seized in the EU as of April 2022 was very small. The data tabulation was reported by the Irish Times from a leaked internal EU document and appeared on April 21, 2022.

We are waiting until the last bell

The list of Novaya Europa includes eight companies which announced the sale of their Russian assets only at the end of the second year of a full-scale war. Almost all of them, except for the Belgian brewing company AB InBev, managed to come to an agreement with the Russian authorities and received consent to the deal.

Turkish Anadolu Efes, the owner of half of one of Russia’s largest brewing companies AB InBev Efes, has announced the purchase of the second half from its partner, the world’s largest beer producer AB InBev. The deal announcement emphasizes that the completion of the transaction can be discussed only after its approval by the regulatory authorities. Nothing has been reported that the Russian authorities have given such consent.

AB InBev announced its intention to sell its stake a long time ago — two months after the start of the war. The deal could not be completed for so long, not because the Belgians could not come to an agreement with the Russian authorities, but because “it is a matter of dividing the business at the international level between AB InBev and Anadolu Efes,” says our source in the beer market. And besides, the departure of the Belgian company turned out to be very conditional: AB InBev managed to leave without leaving, because it owns 24% of the shares of Anadolu Efes. This means that the European brewer will continue to earn money on the Russian beer market, but will retain its reputation.

Among the automakers, Hyundai, Kia and Volvo were late at the exit. Their competitors have already sold factories — but these three concerns were in no hurry to get to the end. At the end of the year Hyundai and its subsidiary Kia, which owned 70% and 30% of the automobile plant in St. Petersburg, received consent to sell their enterprise to the Russian company Art Finance LLC. The Russian authorities said Hyundai would have a two-year option to buy back. And in the third quarter of 2023, Volvo reported it had received permission to sell its truck manufacturing plant in Kaluga, which has since managed to change several owners.

Next to exit

The lawyers interviewed by Novaya-Europa, who are familiar with the plans of the global companies in Russia, do not have a consensus view on how this process will develop further. Some believe that under pressure from public opinion, companies will continue to try to leave. Others believe that everyone who wanted to has left already; the rest have adapted to the new conditions and learned how to earn money in them.

“They will try to get rid of the assets, as the pressure on them is strong,” says one of the lawyers working in Russia, who asked not to be named. And they will do this not because of money, because “there is little economic sense in selling assets, money can’t be withdrawn from Russia anyway,” but “it’s more about social responsibility, reputation, and so on.” At the same time, he believes, “there are those who hope to return to the market which is large and attractive. Bridges are not being burned – they are maintained, and will be preserved. But these are not the same bridges, of course. It won’t be the same as before.”

But not everyone will be able to return: “In the case of someone who has already quarrelled, they will not return here,” the lawyer said, and cited the example of Siemens, which completely withdrew from the energy, engineering and financial business in Russia in 2022, selling assets and stopping supplies and service.

Source: https://assets.new.siemens.com/ — May 12, 2022

Yegor Noskov, managing partner of the lawfirm, Duvernois Legal, has a different point of view. Those who decided in the spring of 2022 that their image losses from continuing to work in Russia exceeded their possible profits have left. “Other companies have found that the profits generated from the Russian market are too significant for their business and exceed image losses, and remain on the market, making record profits”, says the lawyer, and cites Raiffeisen as an example.

This configuration will continue in 2024, Noskov believes: “I think those who left will not return until the end of the military operations, and perhaps not for a long while after.” And those who remain will not sell their business, but will adapt to the situation using either other brands or all kinds of schemes allowing them to maintain a presence in the market, but avoid direct affiliation of the Russian assets with the parent companies abroad, Noskov says.