Selling Desegregation: All the Way Home

All the Way Home

Directed by Lee R. Bobker

Written by Muriel Rukeyser

1957

The United States was on the verge of undertaking desegregation in the mid-1950s, and this new social engineering project was rather controversial at the time. As often as not, it was enacted by judicial fiat rather than via the normal democratic process. In the case of a certain Little Rock school, this was ultimately accomplished by way of bayonets. Various propaganda efforts tried to take a more persuasive approach, however. One of these, released in 1957, was the now-obscure short film All the Way Home.

For a low-budget picture, much effort went into its creation. With 13 credited consultants who assisted the filmmakers, there surely wasn’t a word in the screenplay or a facet of the cinematography that wasn’t calculated for maximum effect. There’s never any doubt about who the audience is intended to admire, or who the bad guys are. But despite all the attention that went into the propaganda, it’s not looking so good in hindsight!

“A quiet street in a quiet neighborhood in the middle of the twentieth century”

An old man — that’s Ed – puts up a “for sale” sign in his yard. The neighborhood is the perfect picture of nice normality that comes to mind when we think of the 1950s, and is practically ripped from a Leave It to Beaver rerun. It’s never stated where the film is set; perhaps it’s meant as a generic “Anytown USA” setting, though some of the accents suggest Virginia.

Then the scene switches to the big city. A brief voiceover tells us that it’s a time of change, including some slightly incoherent verbiage — the film’s only obvious mistake, probably from choppy editing – such as this:

Many [slums] still stand, many torn down, rebuilding of the dispersal of people and neighborhoods, a way being made for the projects. Signs of change in all the cities, and still the dark, red blindness of walls. The cities reach out. The ghettos burst open after a long while, ghettos of every kind. Full borders into the sunny branching section, pushing out to the new country, waiting raw for the builders. Some of us still live in uniformity, but the sifting has begun.

At that point, the scene cuts from housing projects right back over to the ‘burbs again. The meaning is clear: Cultural enrichment is on its way to Suburbia, ready or not. Looks like somebody’s been to film school!

The hate parade begins

It’s not long before Ed has prospective buyers arriving — specifically, blacks — rolling up in what looks like a late-model Ford Fairlane convertible. (What, no Cadillac? No spinner hubcaps, even?) More seriously, this is an intact family, nicely dressed, and otherwise just as respectable as the rest of the neighbors. The only difference, of course, is the color of their skin. Why, they’re just like us – who could possibly object?

Two neighbors see the prospective buyers, and they’re none too pleased. After that, a rotary phone dials offscreen, a sound that today’s young’uns might not recognize. (It’s even more antiquated than modem connection tones. To think, kids these days haven’t even seen AOL trial disks!) Soon the jangling of telephone bells rivals the clock-store intro to “Time” on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon album. With only these audible cues, the viewers are supposed to be shocked at what a hotbed of “hate” the nice bougie neighborhood is underneath its respectable surface. Hell yeah, somebody’s been to film school! Apparently Ed and the Negroes who want to buy his house have become the talk of the town.

The fallout doesn’t take long to waft out of the metaphorical mushroom cloud. First, Ed’s wife gets a brief phone call, which is presumably quite unpleasant. At that, the paterfamilias remarks heatedly:

You mean because of . . . I knew it! I knew it the minute they got out of that car. I knew somebody was going to throw a fit. But who in God’s name would do a thing like that?

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

How beastly! Meanwhile, dissonant and spooky music plays on the soundtrack to cue the viewers into exactly how they should feel about this development. Did I mention that somebody’s been to film school? I wonder, were members of the orchestra notified that their performance would be used to manipulate the audience’s emotions and influence their sociopolitical views?

After that, there’s a scene at a bus stop. Ed gets a cold reception from a fellow member of his lodge. It’s not specified what lodge it is, so that’s left up to the imagination. According to bits and pieces I heard long ago, certain branches of Freemasonry had a reputation for being among the final tepid holdouts of institutional WASP resistance to desegregation.

Then he meets with Ted, a real estate agent, and pointed discussion begins. Ed — ever the tolerant liberal, with decency oozing from every pore — complains indignantly:

Out of line? What in heaven’s name are you talking about? Some people came to look at my house. They were Negroes. I haven’t done anything yet.

After that beginning, the Ed-Ted duet turns out to be an exercise in talking around the issues without naming them. It’s much like the prior conversation with the frosty lodge member. For example, this is how the real estate agent says he doesn’t want the neighborhood he lives in to turn into another ghetto:

I’ve got to consider the community. You’re leaving. There’s a lot of us who are going to be here for a long time.

Such tiptoeing, of course, keeps the discussion in the realm of pure theory. The white audience members therefore hopefully won’t fill in the blanks about the actual implications of what might happen if colored people begin arriving in droves in their own neighborhood. Maybe not all of their new neighbors would be upstanding, high-class blacks such as the family who checked out Ed’s house.

Oh, those narrow-minded bigots! Have they no decency?

Back at the ranch, someone in a car throws black paint on the “for sale” sign, which also spatters Ed’s granddaughter and ruins her dress. The poor dear is traumatized by the drive-by splashing. (I can imagine the effect on the viewers as they saw the little girl being menaced. Of course it’s just a movie, so it wasn’t real — but the emotions generated by the propaganda were real.) Ed gives a voiceover:

The first sign of the first family entering, the street responds with the old questions. Why do they go where they’re not wanted? Why in a neighborhood like this? Now the old cries: running the place down and values down, wanting our girls. Now images rise up: riots at night, murder, rape, images of violation, fears that lie deep in people’s lives.

This bit of monologue was surely inserted by the filmmakers to portray segregationist rhetoric as grotesque, unfounded, and irresponsible alarmism. There’s just one problem. That hardly turned out to be wild fearmongering, given the epidemic of race riots that began in the 1960s (and making a reappearance in recent times), as well as a massive crime wave that didn’t even begin to level off until the early 1990s. Aside from that, there were reasons why segregation existed in the first place, including criminal predation and the reprisals which followed. After the disastrous Radical Reconstruction, separating populations that didn’t get along was a sensible measure to avoid further violence.

Eventually that began to fade from living memory, and the lessons started to be forgotten. Then Leftists took it upon themselves to mix up the populations coercively. If Congress was unwilling to do what they wanted, then the liberal Warren Supreme Court could be counted on to exceed its authority and legislate from the bench, thereby delivering one of those “landmark rulings” such as Brown v. Board of Education. Meanwhile, the Left demonized white opposition, endlessly harped on minority grievances, and churned out anti-white agitprop. Rather predictably, these factors contributed to the turbulent and violent 1960s.

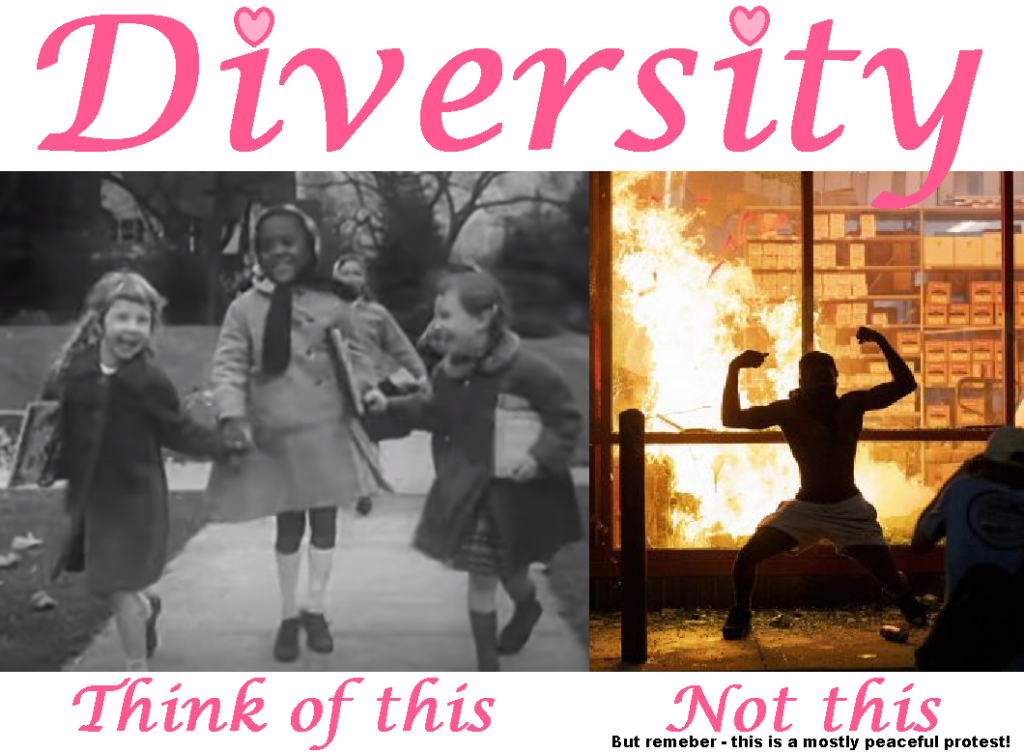

Sometime after the drive-by splashing incident, Ed takes his granddaughter to the schoolyard’s playground. His neighbors are openly talking about him. He masterfully puts on another liberal “Have they no decency?” facial expression. Then he performs another voiceover monologue extolling the virtues of diversity. As he does so, images roll past featuring black and white children happily walking down the sidewalk together. The schmaltz is so strong I can smell it!

Then it’s back to Ted the real estate broker. He tries to convince the local banker not to give mortgages to blacks. Ralph is not having it, and speaks with forced patience and barely-restrained condescension, as if he were gently correcting an unruly child. The banker is an economite — a “practical man,” as he puts it — who only considers the bottom line. He comes up with this:

Now, here’s an article reported in the New York Times which says that the official organization of home appraisal experts finds that land values actually have gone up in this type of situation.

Good one! The banker actually hands over a newspaper that was right there on the desk. Cool deal — so he subscribes to the NYT, and that day’s edition just so happened to have a front-page article that supports the political argument he was trying to make. (Wouldn’t fetching the prop from a filing cabinet seem less contrived?) Ted objects, stating:

You can do anything with figures; you know that. The important thing is we don’t want anything like that to happen here. I’ve got two daughters, you know.

The banker is unmoved. I’ll have to say that it’s an insightful illustration of the typical corporate mentality, a bit too revealing for the purposes of the film. Again, Ralph is an economite, and nothing has value to him unless it has a price tag. These are the types who will wreck primeval forests, move small-town factories to foreign sweatshops, sell dodgy pharmaceuticals, pollute as much as they can get away with, and to hell with the consequences so long as the money rolls in. Pecunia non olet. In this case, the safety of Ted’s daughters has no financial implication for the banker, so it’s not his problem.

Moreover, the smart New York Times journalists, citing their “official organization of home appraisal experts,” have Ralph convinced that blacks moving into white neighborhoods will increase property values. Well, that settles the matter, then! There’s an astute businessman for sure. Quick, someone tell Inglewood and South Central Los Angeles that they’re about to be the focal point of California’s second gold rush!

Now it gets surreal

Ed’s wife consults a priest, struggling to overcome her ingrained prejudices. One might almost expect this white-guilt scene to take place inside a confessional booth. (Of course, this is just an actor playing a priest, but for the audience, the scene is intended to put a halo on liberal ideology.) In her southern-fried accent, she begins to unburden herself:

Ed’s wife: What I can’t bear, Ed thinks I am so lovely, so full of the moralities. I looked at that little girl and all her sweetness and blackness and I thought just that.

Priest: Just what?

Ed’s wife: [after pacing a moment] Black. That’s what I thought. Black like them, I thought. And everything I heard as a child came back to me. Don’t go near one, don’t go into cellars with even one who you know. You’ll be killed, you’ll be lying in a ditch dead — or worse.

After her lengthy confession wraps up, the priest dispenses pearls of his holy liberal wisdom.

Then it’s back to the Ted-Ralph duet. The real estate agent warns that “the better element will leave and we will have a slum on our hands.” The banker counters with, “I think that depends on us.” After all, the white neighborhood could embrace diversity instead, and then everything will work out fine.

Following that comes another voiceover. This leads to the final scene, in which the community meets to discuss the situation. Much liberal mush is heard, though with the occasional token dissenter offering a brief counterpoint. Ralph the banker again mentions the NYT article which claims that blacks moving in will increase a neighborhood’s property values. This time, he goes further into detail by citing the source as a University of California study about “nine San Francisco neighborhoods in which Negroes bought homes since 1940.”

Oh, cool, check it out — some liberal professors did a study! The University of California, was it? Does this mean from UCLA, UCSD, UC-Berkeley, or some other UC? Also, what happened to “the official organization of home appraisal experts” then? Was the article real, or was it a product of the screenwriter’s fertile imagination? Either way, someone needs to hurry up and inform Baltimore of the wonderful news: With blacks everywhere, surely a real estate bonanza can be expected at any moment.

You can buy Beau Albrecht’s Space Vixen Trek here.

Ultimately, All the Way Home is open-ended, since it never says what happens after the meeting. It’s unknown if the Negroes close the deal and buy Ed’s house. We never find out if the neighborhood experiences a white exodus, or if everyone ends up holding hands and singing “Kumbayah.” But the audience does discover what Ted’s been up to lately.

It turns out that the real estate broker flipped his strategy. He’s assisting whites to sell their houses and “has maybe ten new commissions” already. Although he began by trying to stem the black tide before it got started, he became a “block buster” profiteering from white flight. Of course, this is intended to make Ted look like a weasel to the audience. Why, it’s people like him who destroy neighborhoods! Others to blame are the “prejudiced” homeowners who are trying to leave while the getting is good. (That means before finding themselves in a crime-ridden ghetto and having to sell their property at a massive loss.) Of course, the film assures the audience that there’s really nothing to worry about.

Since before my time, there’s been much liberal finger-pointing about the failures of integration. The way they tell it, the reason desegregation didn’t work as advertised is not because its premises were wrong, such as the viability of multiracialism, the sameness of races, and the exchangeability of populations. Instead, integration was a disaster because white people didn’t believe in the program enough.

The blacks themselves are never called out for ruining the neighborhoods they take over, of course. Even blacks blame white people for forcing them to live in ghettoes. (That’s rather silly, since de jure segregation ended long ago and discrimination is prohibited under federal law.) It’s as if they believe the quality of a neighborhood is determined entirely by geography, and has nothing to do with the people actually living there. The irony completely escapes them that many run-down ghettoes used to be nice white neighborhoods until blacks took over.

Finally, the filmmakers were a bit too hard on Ted, portraying him as a weasel, at least according to their own noble standards. In the end, he allied himself with multiracialism, because that’s where the “smart money” is. (Bonus points if you catch the reference!) It doesn’t say who’s buying the houses that his white customers are selling, but if the real-life pattern applies, it means he’s offering them to blacks. Although that much is slightly speculative, it is certain that Ted has become an economite, just like the banker he argued with earlier — and bidness is bidness is bidness is bidness is good.

Who came out with this propaganda?

With the passage of time, this movie’s intended audience is left rather murky. Was it shown in classrooms, on television, or both? It’s unclear how it was distributed, but the typical short films made for school during those times tend to look different. With a run time of a little under half an hour, All the Way Home was ideal for TV. Commercial breaks in the 1950s tended to be modest, and it would’ve been a perfect fit if the end credits had been trimmed.

I always assumed that heavy liberal indoctrination on the idiot box began with Norman Lear, but perhaps it started much earlier. Maybe the eminently politically-incorrect priest, Father Leonard Feeney, was onto something when he wrote in The Point that “[h]aving a television in your home is like having a Jew in your living room.” He said so in 1957, so it’s entirely possible that he had this show in mind, or others like it. The film now appears in a C-SPAN archive, the evidence suggesting that All the Way Home made its début on the electric rabbi, and that it was inherited through corporate acquisitions.

Who tried to bamboozle the public with this diversity propaganda? Details about the production company behind it are somewhat scanty. The opening scene says it was “[p]lanned and Produced as a part of A Series on Changing Neighborhoods by Dynamic Films, Inc.” Another film they produced on this same theme was Crisis in Levittown, PA from the same year. (Their only other politically significant feature appeared in 1958: An American Girl, about a Jewish teenager who reveals her ethnoreligious identity.) All told, this small production company from Manhattan’s Upper West Side released only nine films back in the day, including five documentaries about automobile racing. It’s not clear who hired them to go woke, but surely there’s a story in it.

What seems a bit odd is that none of the actors are credited. One sharp observer noticed Art Smith in the film. He — and possibly some other pinko actors — would’ve had a reason to go incognito, since he was on the Hollywood blacklist. (This instance of “McCarthyism” generally involved a forced career change lasting about a decade, which in retrospect seems harsh to some. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union convictions for anti-Soviet agitation led to a minimum sentence of five years in the gulag.) In any event, he really knocked it out of the ballpark as Ed, the conscientious liberal undeterred by “bigotry.” Good work there, Comrade Smith!

We know who the other principals in this flick are, since they’re credited, unlike the actors. Nathan Zucker was the producer, Lee R. Bobker was the director, and Muriel Rukeyser was the screenwriter. (Golly, that lineup sure sounds just like it came from the passenger manifest of the Mayflower, doesn’t it?) The final scene gives a shout-out to “the committee under whose guidance this film was made,” which included lots of other Plymouth Rock descendants. In the order they are listed in the credits, these are:

- Oscar Cohen — Anti-Defamation League of B’Nai Brith

- Galen Weaver — Congregational Christian Churches

- Harold A. Lett — Division Against Discrimination, State of New Jersey

- Lillian Hatcher — Fair Practices and Anti-Discrimination Department, United Auto Workers

- James H. Scheuer — Housing Advisory Council, New York State Commission Against Discrimination

- Madison S. Jones — National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- Algernon D. Black — National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing

- Alfred S. Kramer — National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A.

- Reginald Johnson — National Urban League, Inc.

- Frank S. Horne — New York Commission on Intergroup Relations

- Charles Abrams — New York State Commission Against Discrimination

- Edward Rutledge — New York State Commission Against Discrimination

- George Schermer — Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations

A dream team like that seems a pretty impressive talent pool for a films that runs only half an hour! If they needed any more propaganda firepower than that, they would’ve had to bring in a heavy hitter such as Edward Bernays, or maybe Herbert Marcuse with the Blue Suede Shoes. What I’d like to know, though, is what’s up with all these Congregationalists and Church of Christ dudes? So many coincidences about them!

In retrospect

This film has not aged well. To give the liberal position more credit than the darlings deserve, in 1957 it wasn’t yet clear what the results of desegregation would be. Surely they thought of it as a noble effort that would eliminate inequality between the races, and soon enough everyone would coexist in mutual harmony. As the 1960s came to a close, however, the results of integration were obvious for everyone who cared to see. It turns out that the segregationists had been right about everything they predicted.

Unfortunately, the liberal politicians and judges doubled down on the faulty social experiment. (Again, they believed desegregation wasn’t living up to their golden promises because white people weren’t trying hard enough to make it work.) Large swaths of entire cities continued to become run-down no-go zones. The usual suspects still aren’t giving it up even after more than half a century of failure. As I’ve mentioned before, the decades of creeping urban blight are approximately comparable in terms of aggregate property degradation to the results of a limited nuclear war.

All told, the film rates a solid eight on the Chutzpah Meter. Consider the irony: A neighborhood is at risk of becoming a ghetto, which would mean its original residents will undergo ethnic cleansing and have to sell their property at a major loss — yet the show depicts whites as the sole aggressors. Precious, isn’t it? That’s not quite how it rolled in Philadelphia, Detroit, and countless other cities and neighborhoods that were built by whites only to be overrun by hordes of urban orcs.