On the Border of Right and Wrong: The Iran-Contra Affair, Part 1

Part 1 of 2

The Iran-Contra Affair is an almost forgotten relic of the 1980s. The story of the episode has been overwhelmed by the spectacular events which followed: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Persian Gulf War, and so on. In the late 1980s, however, the Iran-Contra Affair dominated the news cycle. This was in part due to its absurdity, and it was grist for the mills of the comedy shows of the day.

The Iran-Contra Affair was in fact no laughing matter. It represented a clash between different policy strategies, all of which were plausibly in America’s best interest, and it nearly destroyed Ronald Reagan’s presidency. It also raised important questions. When and how should America intervene in another country’s civil war? What was the best strategy for turning back international Communism? Was the Monroe Doctrine, which aims to prevent European powers from interfering in the Americas, still applicable?

In brief, the controversy was about Iranian-backed Shi’ite militias in Lebanon who had kidnapped Americans and others and were holding them hostage. Several United States Naval Academy alumni and Vietnam veterans on Reagan’s staff then sold weapons to Iran in order to get the hostages released. Then as now, Iran and the United States were at odds, however, and the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-81 was still a recent memory. This made the sale an unusual move, as well as one that went against US policy, and it therefore horrified ordinary Americans when it was made public. The profits from the sale were diverted to anti-Communist forces that the US was controversially supporting in Nicaragua. These were the Contras, from the Spanish word for “against,” who were a particularly violent resistance movement fighting the Soviet-backed government of the Sandinistas, who had seized power in 1979. This diversion of funds to the Contras was possibly a violation of US law. Thus, there were complex nuances throughout the affair. What is certain is that Reagan’s administration and the US Congress had different views on the matter.

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan was a B-List Hollywood actor who became politically active in the late 1940s. He was as far to the political Right as a mainstream politician could be at the time, and first came to prominence by opposing California’s Left-wing activism as Governor from 1967 to 1975. Reagan represented a new style of American conservatism that was deeply anti-Communist and which believed in neo-liberal economic policies with nearly religious fervor. An unspoken agenda item for conservatives in Reagan’s camp was to overturn the “civil rights” revolution. But Reagan’s style of conservatism was revolutionary and did not make up the whole of the Republican Party at the time, and he had to scramble to find a running mate who was acceptable to the existing Republican establishment.

Candidate Reagan’s first pick was former President Gerald Ford, but this plan fell through after Ford made it clear that he still had his eyes on returning to the presidency itself (at one point suggesting that he and Reagan should be “co-presidents”). Thus, at the 1980 Republican National Convention Reagan chose George H. W. Bush, who had been one of his main rivals during the primaries, as his running mate at the last minute. Bush was an establishment Republican: an old-stock American who was for business-as-usual, but did absolutely nothing for his fellow whites. Vice President Bush was not a subversive force in the Reagan administration in the same way that Vice President Pence was during Trump’s time in office, but he assembled a parallel team of military advisors — and miscommunication and working at cross-purposes followed.

President Reagan — at least when he had a script, microphone, and a camera — was truly a great communicator. In cabinet meetings, however, he was not a decisive force. He tended to dither and seek middle ground. One such case occurred after the terrorist bombing of a US Marines Barracks in Beirut in October 1983, which killed 241 American military personnel and wounded many more. Several weeks later, Reagan ordered the USS New Jersey to fire on enemy positions around Beirut in response, but the old battleship’s shells only hit random villages and rubble in Beirut — when they hit anything at all. The bombardment changed nothing in Lebanon and probably didn’t kill a single terrorist. It was an inadequate response.

In meetings, administration officials clashed over what came to be called “Reagan’s Brain” in an effort to control the direction of national policy. As a result, tempers flared, and palace intrigue didn’t make things any better. Moreover, Reagan tended to sign things without reading them.

President Reagan’s times

When Reagan was elected on November 4, 1980, the Cold War was in full swing. Saigon had fallen to the Vietnamese Communists only five years before, and the Soviets had invaded Afghanistan on Christmas Eve the previous year. The American economy was being hit with extreme inflation. And for reasons mostly unrelated to the Cold War, Iranian “students” had swarmed the US embassy in Tehran and taken the staff hostage in November 1979. The hostage crisis was a major campaign issue in 1980 and it wrecked Jimmy Carter’s presidency. The hostages were finally released during Reagan’s inauguration on January 20, 1981.

Meanwhile, the civil war that had broken out in Lebanon in 1975 continued to grind on. The country was divided along religious lines, and Christian, Sunni, Shi’a, and Druze militias were all at war with each other, and sometimes the violence spilled over into other countries. Iraq had also attacked Iran in September 1980, leading to a long and brutal war that lasted for nearly all of Reagan’s presidency.

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s collection The Cultured Thug here.

Events closer to home were also a problem. Communism became a serious force in Central America after the Second World War, and in 1954 the US deposed a Communist government aligned with the Soviet Union in Guatemala. Many Central Americans saw the coup as the cause of Central America’s later political turmoil, but the country had been unstable even prior to that time.

In Central America, Communism was aided by two schools of thought that were prevalent there. The first was economic dependency theory, which postulates that Central America is poor because North America is rich. This is not true, since US involvement in Central America didn’t begin until long after North Americans were already economically prosperous due to their work ethic. Nonetheless, the idea was widely believed and caused many to sympathize with the Communists.

The second was liberation theology. Theology matters, and in this case, radical Left-wing Roman Catholic ministers focused on uplifting Central America’s poor through quick political solutions whose origins lay in Marxism-Leninism. The embrace of liberation theology turned out to be an enormous missed opportunity for Central America. The region could have taken in US investments and capitalized on the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt by building factories in their respective countries to provide goods for the US market. Instead, liberation theology focused on replacing large and profitable commercial farms with small subsistence farming plots — and the factories ended up being built in Asia.

Central America in the 1980s was wracked by war. Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala all had ongoing civil wars. President Carter had allowed — or at least tolerated — the pro-Soviet, pro-Castro Sandinistas to oust Anastasio Somoza in 1979, and Nicaragua thus became a Communist country; the Contra rebellion began in 1981. Guatemala’s civil war was mostly contained during the 1980s, although basic human rights were frequently ignored. Honduras was stable and hosted US military forces, although it was governed by a military dictatorship that led to the torture, murder, and disappearances of anyone who was identified as a dissident. Panama remained stable, and the Panama Canal remained a US Territory. Costa Rica, which has a mostly white population, was likewise stable.

What to do about Communism in Central America became a burning question for the Reagan administration. The idea that the Soviet Union would soon collapse under the weight of its flawed ideology was unthinkable in the early 1980s. Pop culture portrayed the Soviet Union as invincible and as an existential threat to the US. Books such as Red Storm Rising and the Hunt for Red October were bestsellers, and the film Red Dawn was a hit. Given the turmoil in Central America as well as fear of the Communist threat, it was entirely possible that the US was going to get sucked into a Vietnam-like war by accident.

The wounds of Vietnam were still fresh in the American consciousness. As a result, in 1982 Congress passed the Boland Amendment and Reagan signed it into law, which was an attempt to limit US involvement in Nicaragua’s civil war. In retrospect, Reagan’s failure to veto this law was a huge political blunder. No presidential administration would survive a second Soviet foothold so close to the United States (after Cuba); something needed to be done about it. The pro-Soviet Sandinistas were not in full control of the country before the Americans intervened, and the rebellion against them began of its own accord, mostly consisting of independent farmers who had suffered as a result of the Communist agricultural reforms. These rebels eventually became the Contras.

Those who supported the Boland Amendment had a point, however, and that point went beyond simple Vietnam War analogies. Communism was gaining ground in Central America in part because of a poor economy and poor governance. Soldiers who were fighting Communist guerrillas regularly abused the general populace. Central America’s political elite was also often corrupt and frequently used torture to remain in power. The Contras themselves were a perfect example of Central America’s problems. The group’s strategic leadership, the Directorate, consisted of white Nicaraguans, while the guerrillas in the field were often mestizos. Those in the Directorate were not well-educated on strategic matters and gave the impression of being yet another out-of-touch, corrupt elite. Members of the Directorate were often found poolside in Miami.

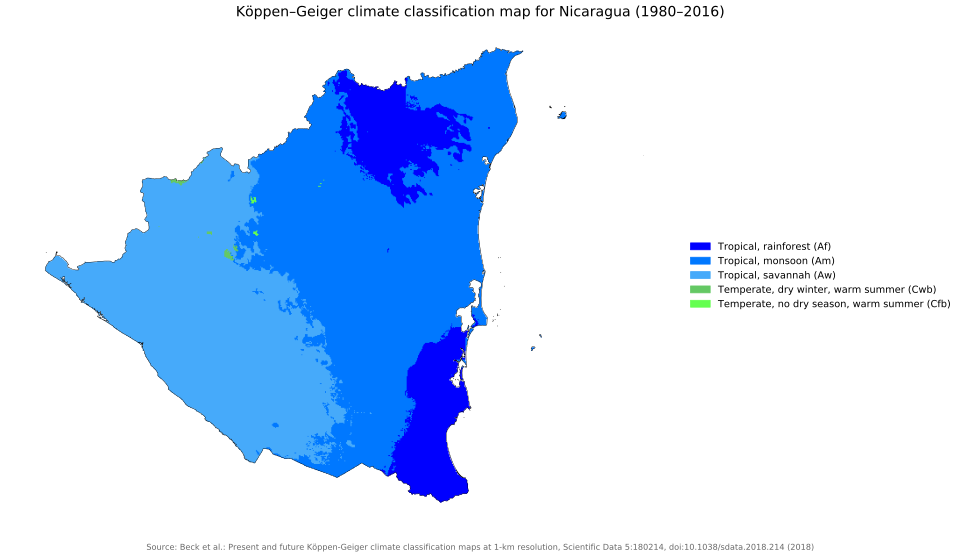

Nicaragua has a tropical climate, and its mountainous terrain is covered in rain forests and jungles.

US operations in Central America

Guatemala’s civil war was also ongoing during Reagan’s presidency, but events in El Salvador and Nicaragua were more pressing. In El Salvador, the Americans sent in uniformed military advisors and plainclothes mercenaries, some of whom were American white advocates, to help the government to fight a rebellion by Soviet- and Castro-backed rebels. (The white advocates who were deployed to Central America is part of the reason why Reagan never got around to reversing the “civil rights” contagion.) The US strategy was to support the government while clamping down on their forces’ human-rights abuses in order to win the public’s hearts and minds. This effort was successful and worked wonders, with some of the rebels defecting to the government. One of them was Miguel Castellanos, who wrote:

With the experiences that I lived through in the [Salvadoran Civil War], and what I saw of the communist model in the countries that I visited, I came to be in disagreement with the Marxist-Leninist doctrine that forms that foundation of [the communist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)]. This doctrine consecrates violence as the midwife of history and maintains that in order to resolve social injustices, it is necessary to form a long-term dictatorship of the proletariat, a dictatorship, a form of government that exercises absolute power, that does not permit opposition, that denies all of the rights of the individual, that denies the people their religious beliefs. This I had seen and understood during my travels. It’s one thing to visit the Soviet Union or Vietnam and have a translator explain things; it’s quite another mater to go to Managua or Cuba where you can talk to people who share with you a history, a culture, a language. It’s very different when you speak with Marxist Leninists in Spanish.[1]

The situation in Nicaragua was entirely the opposite of that in El Salvador. In Nicaragua, the Communists controlled the state, while American foreign policy was to provide aid and equipment to the Contra guerillas who were fighting to overthrow them. But with the Boland Amendment signed into law, Reagan could not support them legally.

Note

[1] William R. Meara, Contra Cross: Insurgency and Tyranny in Central America, 1979-1989 (Middletown, Del.: HBR Press, 2010), pp. 73-74