Passage Prize II: Rewilding

Lomez (ed.)

Passage Prize II: Rewilding

Passage Press, 2023

The Passage Prize is an annual competition for dissident writing, poetry, and art, each round of which produces a book consisting of the winning submissions and many others. Last year’s prompt referred to the fact that domestic pigs released into the wild will change to more closely resemble wild boars. The current volume, published with the subtitle Rewilding, is the result of imagining something similar in the human sphere after an escape from modern captivity. There are many interesting statements here on race, identity, and vitality.

The cover art for the hardcover version was made by an artist going by the name of Wide Dog, who won the previous year’s competition in the art category. It depicts a jaguar holding a domestic cat in its jaws, presumably having just killed this lesser form of itself. The larger cat is surrounded by the narrow stalks of plants which could be taken for bamboo, making it look as if he is still within the bars of a cage, although there is enough space between them that he is no longer confined. The illustration is in a modern, two-dimensional style similar to a collage, but the exaggerated twisting of the animal’s body and the depiction of its face are more reminiscent of traditional Chinese or Japanese painting. Perhaps he has more to do before he can return to his natural environment and rewild, as jaguars are not native to Asia.

The writings in the volume cover a range of topics, from romantic relationships to science fiction, but several make explicit reference to our current political situation. The third-place prize winner in fiction, “Dogwhistle,” is a near-future scenario in which a team of artificial intelligence researchers has been able to train dogs to bark in such a way that it can be translated into human speech. But the dogs do not celebrate diversity, neither among human beings nor dog breeds; their speech soon consists mostly of racial slurs, along with excerpts from Adolf Hitler’s speeches.

The researchers initially attempt to cover this up, but their data is released to the public by WikiLeaks, allowing a Chinese company to create a cheap dog translator and sell it on Amazon. Soon, millions of people have direct evidence of how racist their dogs are. The European Union and Canada then make if a felony to possess such devices, and several US states also ban them, but they remain easy to come by.

The narrator’s father, Rex, is a dog trainer with a popular streaming show, and takes on the daunting task of training the dogs to be more tolerant. Despite his extraordinary efforts, this is the one thing he cannot teach them, and after several months he finally gives up. By this point dogs are widely euthanized and cats are beginning to replace them as man’s best friend. One night in San Francisco, an anti-racist mob rounds up over a thousand dogs and burns them to death. Rex is inundated with hate mail using language similar to that of the animals, his show is banned from every major social media platform, and after one of the family dogs is stolen from their home by anti-racist fanatics, he commits suicide in despair. His surviving family members then put all but one of the remaining dogs to sleep.

The narrator ends by considering the timeless question of nature versus nurture. His father had taught him that “there are no bad dogs, only bad owners,” and this was certainly what the extremists who had flooded Rex with hate mail seemed to think. He recalls his father acting on this belief in the past, when he attempted to rehabilitate a former fighting dog for a miniseries. But the dog mauled one of the crew members during the filming, and she was later put to sleep. He concludes with relevant wisdom for our current human predicament:

Maybe there’s only so much you can do to change a dog’s nature. It’s not always our fault. Maybe it’s just the dog.

One piece which one could easily imagine as a true story, but which was a prize winner in fiction, is entitled “Redemption.” This story has none of the imaginative or fantastical elements which are common in the volume’s other stories, but makes an important point which to this day is rarely honestly discussed in the mainstream. The narrator describes his childhood in Hamtramck, Michigan during a time of changing demographics. As part of a working-class Polish Catholic family, he was initially surrounded by his own kind. The Poles, Italians, and blacks all lived in their own neighborhoods, and neither he nor anyone he knew saw a problem with that. But unfortunately, higher authorities thought differently.

After the 1967 riots and the razing of negro neighborhoods to make way for a new highway, blacks began moving into Hamtramck, with the aid of major loans from non-profits. As the color of the neighborhood began to change, so did the atmosphere. It became, as the narrator, Michal, puts it, “saturated with a feeling of ever present danger” as black violence became commonplace. A judge ruled that the city and local realtors were in the wrong for “colluding to keep black homebuyers out of the market,” after which there was nothing to prevent the area from darkening further. Michal observed the changing school environment; the newcomers “disrupted class . . . kept to themselves . . . [and] acted like they were in charge.” At one point an old man going for a nighttime stroll was attacked and beaten in the street. Michal could not pinpoint exactly when the neighborhood reached a terminal condition, but whites increasingly sold their homes, and soon his family followed.

With their move to a new neighborhood, the family lost the African ambience, but also their Polish identity. Their former community had been close-knit, while in the new one they knew no one, with the exception of a few fellow Poles who had moved along with them. The father, Aleksy, attempted to preserve the tradition of speaking Polish at the dinner table, but Michal’s brother found this absurd, and eventually it was abandoned. Their new church was Catholic, but of no particular ethnicity, and soon the children all thought of themselves as simply American. Aleksy was the one who was most attached to tradition, but Michal and his other siblings all but forgot about their Catholic beliefs.

At school, his sister was made to feel guilty through lessons on something called “white flight,” although it was unclear what exactly the white flyers had done wrong. His brother married a more well-to-do woman named Holly who worked for a non-governmental organization and vocally shared these newly-established “correct” politics. One night at dinner, Holly insists on hearing their father explain why they left Hamtramck. Aleksy bluntly explains that it was because blacks had ruined everything, but he does not use the word “blacks.” She responds only with a look of shock. Michal’s wife is also offended, and afterward is horrified at the idea that he may also be infected with his father’s “racist” views. Aleksy is ultimately buried in Hamtramck, as is his wife, at his own insistence.

After his parents’ death, Michal is visited by his brother, who asks him what his “real thoughts” on the issue are. He responds that his father “was wrong, but not in the way you think.” His brother shows no curiosity about what he means by this. Michal explains that since his own children never knew their grandfather well, he will tell them everything about him. As he puts it:

History is full of people who vanished. Some were totally wiped out in war, but most passed away when the new generations simply forgot who they were, and they became something else altogether. I can’t bear the idea of my kids forgetting who they are.

He silently adds that he has a chance to regain his lost identity through his children, while his brother has only a German shepherd.

The additional stories offer other, more creative interpretations of situations which should be familiar from real life, particularly to dissidents. One by Gabe Mamola deals with a great artist whose work becomes popular as a meme among online “racists.” He is aggressively questioned by a reporter on the subject, and responds in confusion that he does not have to defend his work.

Soon afterward, the public becomes aware of a “racist” black barbarian character he had created years earlier. He is then “cancelled,” suddenly losing all of his customers. It is implied that the black man who posed as the barbarian publicized this information out of envy, as he remembered the artist’s opportunity to sleep with a beautiful white woman in the past. The artist, however, continues to paint for the love of it.

“Song of the Son of Stone” tells the story of a strange humanoid creature with exceptional skill in dealing with stone who has been toiling for as long as he can remember in the service of a human city which he helped build. He is compensated, but no more than anyone else, and the money is of little use to him given that he does not have the same material needs as men. He has few emotions and cannot ever remember anything but “drudgery.”

One day in the course of his work an enormous, broken slab of unintelligibly engraved stone catches his interest, and he decides to take it home with him. He always hears the “song of stone” at night, but this stone is different; it asks, “Can you hear me, brother?” The “stone man” is overwhelmed by emotion and feels compelled to travel out into the desert in search of the remainder of the mysterious artifact. When he returns with the other half of his new “sister,” he finds he has been banished from the city, and the city guards give him no explanation.

He hides the slab, sneaks back inside the city walls, and finds one man who can tell him what has transpired. Avran the overseer explains that as he was “absent without leave,” the tower which the lord of the city had commissioned was not completed on time. Since he had always been more productive than the others, the human masons blamed him for the delay, and the lord declared him an outlaw. As the stone man puts it, as soon as he put himself “ahead of the others, the veil was torn down and the true nature of society, and my place in it, revealed.”

Guards are posted at his home, preventing him from reaching the other half of the sentient slab. He struggles to escape the guards and the angry mobs that have mobilized against him, killing some of them and even climbing up the lord’s new tower, but soon he is overcome and smashed to pieces. His only consolation is that he has brought the lord of the city down with him. But his spirit survives, and he hears a song explaining that it is not in his nature to be as unfeeling as stone, but that his “humanity was gradually eroded by [his] acceptance of the daily grind of unrewarded work as the only expression of [his] existence.” The stone man waits to be reincarnated, secure in the knowledge that he will now remember his own history.

The short stories here are mostly tragic, but the shortest is also the most uplifting and the most relevant to the ordinary reader, offering a simple prescription for liberation which practically anyone can follow. For the most part, the written pieces and the various forms of visual art on display here were submitted by different people, so the fact that they are arranged appropriately, as if the illustrations were made specifically for the accompanying stories and poems, is presumably due solely to the talent of the woman who did the layout. But in the case of “Please Stand Clear of the Closing Doors,” both the short story and the eponymous image were contributed by one David Petrides, and are clearly intended to go together.

The illustration portrays three vague figures in a subway car resembling unfinished 3D models for a video game. Two of them are hunched over on benches, but one is standing up proudly and looking outside through a large opening, as if one entire end of the train car has been torn away. The world outside is bright and beautiful, with a simple blue sky over green grass. The man himself is the only other element of the image who has any color; everything else is gray.

The story is only a single page long, and describes a man who lives in a similarly bleak environment, feeling isolated, sick, and “out of joint with his entire world.” One night while surfing the Internet on his phone he comes across an old video of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who is comparing the pleasure of great exertion in the gym to an orgasm. He is inspired and begins going to the gym regularly. The others there are not bodybuilders, only more “gray people,” but the heavy equipment is there, and he makes use of it.

Soon he finds that with greater physical fitness he develops a greater appetite, and he begins to improve his diet, replacing the “packaged slop” he had been accustomed to with steak and eggs. He develops an appetite for books as well, and soon feels “an otherworldly color burning inside of himself.” After a year, he has somehow found an opportunity to move somewhere that might better reflect his new spirit. He steps onto a train car, on his way to the airport with a one-way ticket. The other denizens of the gray box look at him strangely, as “he almost seems to be bathed in sunlight.”

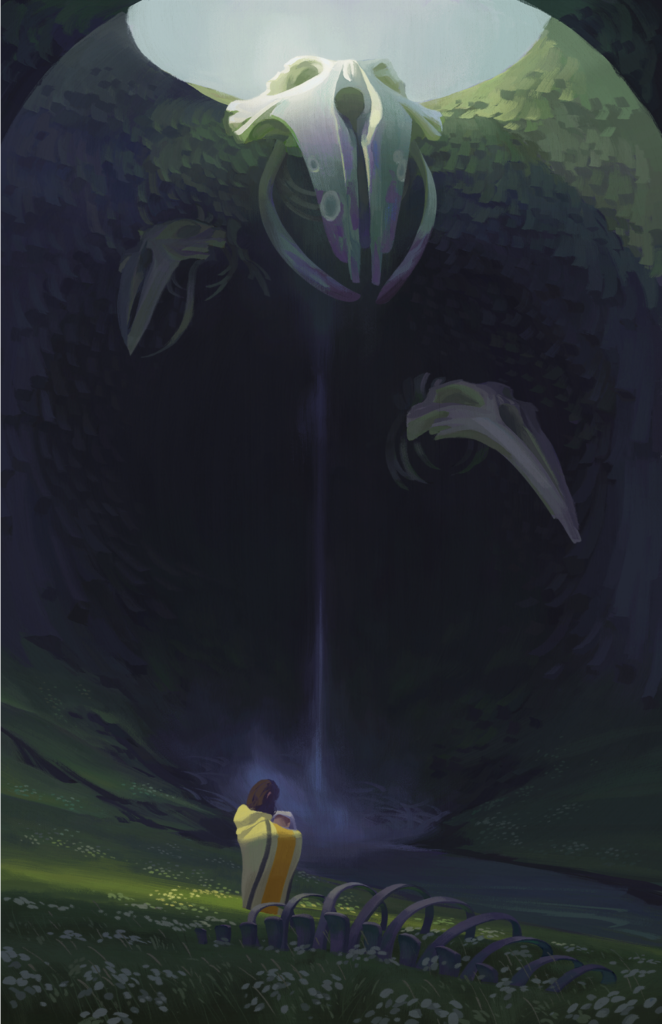

French dissident sculptor Fen de Villier was the art judge for this year’s contest, and his choice for the second-prize winner was a submission entitled Sojourn Landscapes by Andrew Yan. This set of three paintings depicts imaginative outdoor scenes, which, as the judge notes, give a sense of nature’s grandeur. In the first piece, a female figure in a colorful robe stands at the bottom of a deep, round pit, and the viewer can barely discern that she is holding a baby. She is dwarfed by an enormous skull in the wall of the pit above her, which resembles something between a whale skull and a fountain pen, and that seems to look down on her like a hostile god. Two other skeletal features in the wall could at first be mistaken for hands or flippers, but upon closer inspection they are also skulls. Something vaguely like a ribcage lies on the ground next to her, which could be that of a similar creature.

Most of the pit is in darkness, although the uppermost skull is in bright sunlight, and the sky is visible above. There is also a patch of light on the grass around the woman, and a thin, white line ending in mist, apparently a waterfall flowing over the wall in the distance. We cannot see the woman’s face, but what we can see of her and her surroundings gives the impression of someone maintaining health and vitality despite being in a gloomy and oppressive environment.

The next image in the series is much less human, depicting a mountain valley landscape that is partly covered with snow. There is no sign of animal life anywhere, or even any trees. The closest thing to a character in this landscape is the Sun, which is creating an enormous rainbow through its reflection on a strange river that is shaped like a tangle of roots. The impression is of a halo in a religious icon, as if the valley itself is a radiant saint.

The Sun plays an even larger role in the final image, which is twice the size of the previous two, but there is a human presence as well. A white Humvee is driving down a road in an open space, and is about to pass under the end of a line of street lamps, as if it is leaving an urban area. Possibly on his way to a camping trip, the driver is heading toward the Sun, which dominates the simple landscape with another dramatic light effect. Here the halo is shaped like a human eye, but has identical corners, as if it is neither left nor right. That the Sun is the main character here is emphasized by numerous solar panels on either side of the road that reflect its light. There is nothing of the “cute” aspects of nature which might be familiar to the average city-dweller of today — not even a single dramatic gopher — but the driver is surely undeterred by this. As the art judge points out, the artist conveys a sense of magic and “comforting solitude” which can only come from nature.

As with the previous volume, there is not as much to say about the non-fiction here, as there is not much of it. One essay comments on modern art via the life of one of the earliest modern artists, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). The French painter seems to have had a questionable understanding of human anatomy and bad taste in color choice. Several of his paintings were direct imitations of existing works, and not very good ones. He was nevertheless very successful from a young age, apparently due to political connections. Although he was an orphan and may have been the illegitimate child of another man, his official father was a deputy to the French National Convention which ordered the King Louis XVI to be executed, and one of his fans was a future French President. As in contemporary modern art, powerful people had a higher opinion of his work than the public.

The essay is frankly verbose and flamboyant at times, but does include some interesting points about the mindset behind modern art. The author’s first experience with art was at the Art Institute of Chicago, where old women insistently told him what to think and feel about the artwork on display. As he puts it, they clearly felt that they had the single correct explanation for every piece of the exhibited material in their guidebooks. But at the same time, “when they felt cornered, the Nice Old Ladies thought they could write off whatever was incoherent or inconsistent in their opinions by saying, ‘It’s all subjective.’”

He characterizes modern academics as having a similarly solipsistic attitude: “Rather than advancing an opposable opinion, their modus operandi is to humiliate you for being so backwards as to expect a straightforward answer.” Both are connected to a long-standing rejection of any standard which is not purely subjective and individual, such that the artist is no longer expected to fit into any tradition or even to be comprehensible to any audience beyond himself. The author concludes by calling for a “spiritual revolution” — a return to the traditional love of talent and beauty and a contempt for ugliness.

There are several poems throughout the book, but some of them seem to consist of obscure symbolism I could not fathom. There are others, however, which are more straightforward. Submissions entitled “Tidal Boar” and “Song of Life” fit quite explicitly into the stated theme of wildness and vitality, as they deal in energetic language with wild animals. The latter is a brief characterization of the conflict between domesticated life and freedom, or as the text puts it:

Between a frenzied lust for city scraps,

And something else, a need that never ends —

The itch to steer once more toward the sun,

To crest the wind, and rule the shining sky.

There are other pieces dealing with relatively mundane human activities such as fishing and divorce, but one poem by Alexander G. Rubio is an especially beautiful reflection on nature. The poet conveys the seemingly unchanging nature of a sandy desert and its appeal to those who have no such stability. Another particularly impressive piece in terms of aesthetics was submitted by Will Davis and describes the appearance of a city in sinister, even paranoid terms.

There are watercolor depictions of pigs and boars throughout the book, gradually becoming wilder until the final image, in which a boar seems to have recently devoured another animal. I did not feel any more carnivorous when I finished reading, although perhaps I was not doing so in the right environment to trigger the intended transformation. As with the previous volume, the writing and visual styles vary widely, so the reader who enjoys some of the submissions will likely dislike others. At times I got the impression that certain contributors must be autistic. I was impressed by the creative spirit here, however. Even the gloomiest contributions are encouraging in the way in which they demonstrate the level of talent on our side. The back of the book is embossed with the words “We are going to win,” and this is the feeling much of the book conveys.

Submissions for the next round of the prize will remain open until March 1. These can be any previously unpublished work; visual art, fiction, non-fiction, or poetry is welcome. Contributors can win up to $1,500, and everyone whose work is selected for publication will be paid.