Rescuing and Retoring Spain

Arthur F. Loveday

Spain 1923-1948 Civil War and World War

Allentown, Penn.: Antelope Hill Publishing, 2022

(originally published in the United Kingdom in 1948)

Of all the nations that make up Western Civilization, Spain was the first that faced and overcame the challenges that eventually troubled all the others. In the 1400s, Spain threw off the Jewish yoke and freed its government and society. A century later, they also expelled the Muslim settler-colonists. Then, in the 1930s, the Spanish defeated a Soviet-led effort to carry out a Communist revolution in their country.

In 1948, when the Spanish Civil War was still fresh in the minds of the British public, Arthur F. Loveday wrote a book about the war. It was the right book at the right time for the right audience. The British public and establishment had remained on the sidelines during the Spanish Civil War but leaned toward the Spanish Left, which included many Soviet-controlled Communists. In 1948 it was absolutely vital to British interests that a British patriot should explain the truth of what had happened. Spain 1923-1948 is now in the public domain and was republished in 2022 by Antelope Hill Publishing.

The Spanish Republican government was made up of an alliance Leftist factions, some of which were directed from Moscow.

The British public’s leftward lean was due to the bias of the British the media and clergy, which was underpinned by the metapolitical work of organizations such as the Fabian Society and the Labour Party. During the 1930s, liberals were bedazzled by Soviet propaganda and were unable to see the cruelty of Communism. Liberals rationalized the deliberately engineered terror-famines, gulags, and secret police. They also romanticized the dysfunctional Spanish Republican government. The siren song of Communism even beguiled otherwise well-meaning Old Stock Americans.

By 1948, it was clear that Western Europe needed to unite to counter the Soviets threat. NATO would not be formed until April of the following year. Spain at the time was a pariah state due to the victory of Francisco Franco’s “fascist,” anti-Communist regime in the war, but also had a large, battle-hardened army. Spain is difficult to invade, and historically it is where small armies are destroyed and large armies starve. It makes up most of the Iberian Peninsula, and apart from its border with Portugal, it is surrounded by protective seas, while its northern border is secured by the Pyrenees mountains.

As John Beaty wrote in his excellent book, The Iron Curtain Over America:

With the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, and the lofty Pyrenees Mountains as barriers; under the sheltering arm of distance; and above all with no visible internal Communists or Marxists to sabotage our efforts, [the Americans] can — if our national defense so requires — safely equip Spain’s eighteen well-disciplined divisions, develop airfields unapproachable by hostile ground troops, and in the deep inlets and harbors of Spain can secure safe ports for our navy and our merchant fleet. Our strengthening of Spain, second only to our keeping financially solvent and curbing Communists in this country, would undoubtedly be a very great factor in preventing the Soviet leaders from launching an all-out war. Knowing that with distant Pyrenees-guarded and American-armed Spain against them, they could not finally win, they almost certainly would not begin. Our strengthening of Spain’s army, potentially the best in Europe outside of Communist lands, would not only have per se a powerful military value; it would also give an electric feeling of safety to the really anti-Communist elements in other Western European countries.

The British had — and still have — an important naval base at Gibraltar from which they control passage to and from the Mediterranean Sea. Spain had been isolated from the rest of Western Europe by the late 1940s, and there was a justified fear that, if the Spanish felt that they had nothing left to lose, they might attempt to seize Gibraltar. It was therefore critical after the Second World War to change the public’s attitude toward Spain.

The defeated Leftists, the Spanish Republicans, maintained a government-in-exile. This pretender government had first fled to France following their defeat in 1939, and then finally to Mexico. This government was sympathetic to international Communism and continued to put pressure on Spain on the international scene in the late 1940s.

Loveday writes:

The powerful, intelligent, and active campaign of Soviet Russia and communism to revenge themselves on Spain for the defeat of 1936-39 bore its magnificent harvest in the debates and motions of the [United Nations Organization]. At the San Francisco conference, on June 20th, 1945, the Mexican delegate proposed that Francoist Spain should be excluded from membership . . . this was a strange and alarming example of lack of principle and resort to camouflage [by Soviet led international communism]. (p. 198)

The Road to Civil War

The roots of the Spanish Civil War lie in longstanding tensions within Spanish society that their Constitution of 1876 had failed to alleviate. Of this, Loveday writes:

In the 55 years under that constitution (1876-1931) there were 56 governments, a seven-year civil war (Carlist), various local revolutions, four prime ministers assassinated, three attempts on the life of the king and finally a revolution, which led to the terror and civil war of 1936-39. (p. 217)

Besides their constitutional problems, Spain also had two ethnic groups which were uncomfortably united under a system where Castilians were politically dominant. Most of the people in Spain speak Castilian, which is what English-speakers call Spanish. In the eastern region of Spain, Catalan is spoken, and in the north, the unique non-Indo-European Basque language predominates. The Roman Catholic Church attempted to ease tensions by emphasizing their common religion, but this led an ethnically-fueled anti-clerical movement which the Communists exploited.

These ethnic tensions, combined with Communism and other forms of Leftism, led to considerable problems for the Spanish government in the early twentieth century. Events abroad likewise poisoned Spain’s domestic scene. In 1919, for example, the Spanish army was mired in a quagmire in Morocco. Terrorist gunmen ran rampant through Barcelona. These problems only ended when an aristocrat, Miguel Antonio Primo de Rivera (1870-1930), took over the country and established himself as a dictator under King Alfonso XIII in 1923.

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s The Tyranny of Human Rights here.

De Rivera only ruled Spain for six years, during which order was restored and the war in Morocco successfully won. But de Rivera was undermined by the Leftist factions, including the Masonic Order of the Grand Orient as well as the Communist International. Both organizations included large contingents of Jews. The value of the national currency, the peseta, fell during this time, although the economy was stable and the nation’s credit was improving. (It is possible that Jewish bankers involved in currency exchange manipulated the value of the currency in the Zurich and Amsterdam exchanges.)

The biggest problem for de Rivera was the army. Artillery was a branch unto itself; it was independent of the Ministry of War and had its own regulations. When de Rivera attempted to address this, the garrison at Ciudad Real mutinied in January 1929. They were put down, but their leader was acquitted in the subsequent trial. Other military garrisons rebelled for their own reasons. The military’s instability finally caused de Rivera to resign in 1930. He went into exile in Paris and died shortly thereafter.

Spain’s destabilization only increased thereafter. Elections were held in 1931 and the anti-monarchists prevailed. King Alfonso XVIII went into exile, but did not abdicate. Spain then became an unstable republic with a large segment of monarchists. On one side of the political divide was the Right, which included conservative monarchists and the clergy, as well as the Falange, led by José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the son of the former dictator. The Falange were the Left side of the Right. Their political platform consisted of 26 points which called for national unity, supported high wages for workers, encouraged the growth of industry, and so on. On the other side, the Left was a collection of anarchists and Communists, some of whom took their orders from Moscow, as well as misguided anti-clerical ethnonationalists in Catalonia.

The fuse for civil war was lit in February 1936. An election was held which resulted in an unexpected victory for the Left under the umbrella of the Popular Front. Loveday writes:

The official figures of votes, as given at the time by the Spanish Government itself, are: Popular Front, 4,356,000, Parties of the Right 4,570,000, Center 240,000, or a majority of Right and Center over Popular Front of 454,000. This was the result, notwithstanding the fact that election irregularities in favor of Popular Front candidates, such as the destruction of the urns and voting papers by the mob, and the falsification of election figures took place in many centers. (p. 41)

While more Spaniards had voted for the Right, the number of Popular Front deputies elected to the Cortes, the Spanish Parliament, was greater due to the arrangement of the various political districts. Once in power, the Leftists reorganized the legislature to increase their majority by annulling the votes for the Rightist deputies and then expelling them altogether.

The Popular Front enacted Communist-style economic forms. Industrial firms, for example, were not allowed to cease operations even if they were unprofitable. The owners had to maintain them or else hand their assets over to the workers. The result of this law was that the workers could strike until a firm was bankrupt and then take ownership of the company. The way in which the workers would break down the actual ownership of a firm was vague, however, and the company might have lost its market value during the preceding strike, leaving such a firm was effectively bankrupt. The Popular Front also attacked Catholics: priests were imprisoned, schools were shut down, and churches were destroyed.

In May-June 1936, a document was discovered which outlined a plan to turn Spain into a Soviet-style state under the dictatorship of Largo Caballero. The Leftists in government then released genuine criminals from prisons and refilled the cells with members of the Falange. Primo de Rivera was arrested and executed by firing squad on November 20, 1936.

The trigger which finally led to the outbreak of civil war was when Calvo Sotelo, a highly respected conservative parliamentarian, was arrested by the police and executed in a police van on July 15, 1936. Loveday writes:

At the core of the conflict was the struggle between those who held the doctrines of (((Karl Marx))) and those who held the doctrines of Christ; the latter based on universal brotherhood and obedience to authority and the other on class warfare and the revolution. There could be no reconciliation between these two ideologies, either in Spain or elsewhere, and the murder of Calvo Sotelo set the light to the civil war between them, which broke out on July 18th with the revolt of the Spanish army in Morrocco. (p. 44)

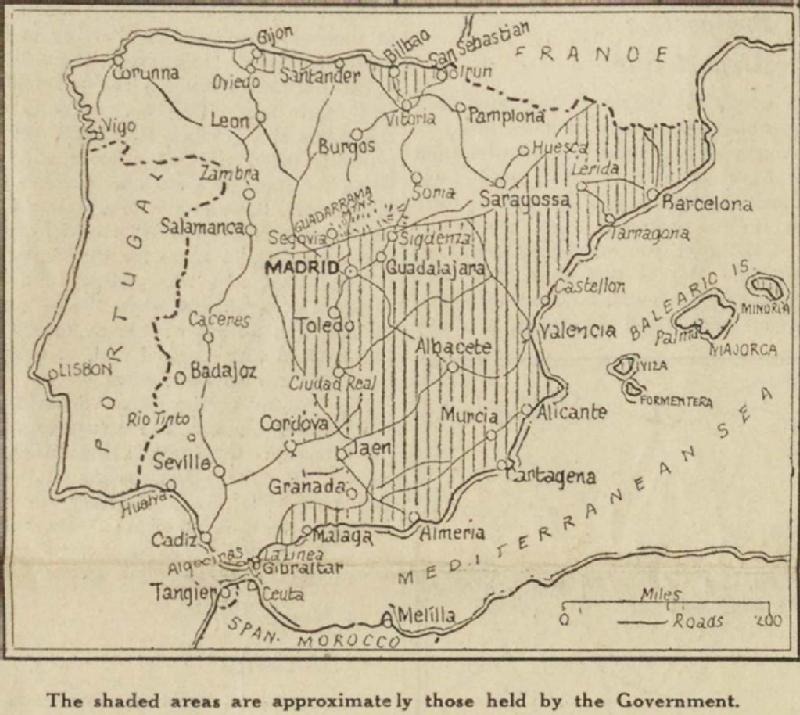

The revolt was led by Francisco Franco. The best troops in the Spanish army were Moroccan mercenaries, and Franco airlifted them, along with his best officers, across the Strait of Gibraltar to end the chaos. It is possible that Franco could have ended the Spanish Republic already at that time, but not all of the military supported him; the Spanish Navy remained loyal to the Republic, for example. Nonetheless:

. . . [T]he populace of the country though which [Franco’s Nationalist Spanish Forces] advanced was entirely on their side; the advance could not have been made under any other circumstances. That this was so, was further borne out by every visitor who went to Spain during the subsequent months and witnessed the fact that General Franco did not have to guard his lines of communication. They also witnessed the traces of the reign of terror and destruction, which had been left in the towns and villages of Andalusia and Estremadura by the retreating government forces; the inhabitants related to visitors how the communist and socialist elements, a minority but an armed one, had massacred the civil guards, priests, and often all members of right party organizations and destroyed and pillaged the churches, the condition of which for a long time continued to be standing proof of the truth of their statements. (p. 52)

Loveday writes:

The contrast between the Spanish Civil War and the First World War was signalized by the French General Duval in the “Journal des Devats,” in which he showed how, on the basis of an army of 750,000 men, General Franco was fighting on a front of 1,100 miles, whereas the allied western front during the First World War was 400 miles and was held by an army of 2,500,00. In Spain there was no consecutive line of trench defenses as in France, for the mountainous character of the country forbade it, apart from the comparison of length to man force. Thus, large stretches of the lines were very sparsely defended, though the division between the opposing sides was everywhere clearly defined. (p. 62)

The war ground on for nearly three years, resulting in nearly a half-million combat deaths as well as further deaths from starvation and disease. With the benefit of hindsight, the whole of Western Civilization should have rallied to Franco’s side, but the poison of Communist propaganda was everywhere. The British dithered, restricting their involvement to their shipping concerns and matters of trade and economics. The Americans were likewise split, albeit in in unusual ways. Ironically, anti-Communist American isolationists supported policies which would have benefited the Leftist Spanish Republic by default, while the Left-leaning Roosevelt administration gave substantive support to Franco through shipments of oil and other supplies.

Propaganda

In the 1930s and ‘40s the Anglophone media was far more restricted and controlled than today. The British Broadcasting Corporation was the central information clearing house for the British Empire and its coverage of the war in Spain. Its coverage was so biased that it was basically propaganda. Loveday writes:

BBC broadcasts made most people believe throughout the war that Franco’s army consisted chiefly of foreigners and Moors, whereas English military experts, who visited the fronts, put the proportion of foreigners, including Moors, in his army at the end of 1937 at a minimum of 10 percent and a maximum of 12 percent. Sensational reports of mass landings of Italian or German troops in Spain on various occasions in 1938, of Italian invasion and occupation of Mallorca in 1937 and of German invasion and occupation of Morocco in 1936 were launched from time to time from the same source and were in every case proved to be false . . . (p. 123)

The bombing of civilians by Franco’s air force was also highly exaggerated. The targets were always military ones, and Barcelona was only struck by air attack because it was the Leftist Republic’s industrial base. Ironically, within a few years the British would deliberately organize their own bombing campaigns deliberately targeting German civilians. The Americans claimed that they were not targeting civilians since they were only bombing during daylight, when more accurate targeting was possible, but this was only a fig leaf covering what was a genuine war crime. The Americans would go on to bomb Japan’s civilians with little global outcry and very little self-reflection.

Spain after the Civil War

When Franco’s army marched into Madrid at the end of the war, it consisted of a column stretching 16 miles. The German and Italian forces marched in this column but returned to their respective homelands shortly after. Following the departure of the foreign troops, accusations that Spain would allow Germany or Italy to possess Spanish territory were finally put to rest.

The end of the Spanish Civil War created a refugee crisis in France. Many Republicans, especially those from Catalonia fled. They were herded into refugee camps, but not until the criminal element among the fleeing masses sacked French villages and committed the usual outrages. The French sought to get rid of them by sending them to Mexico. The first refugees sent there turned out to be hardened communists and the Mexican government stopped taking them in as a result, although they did eventually host the Spanish Republic’s Government in Exile. Franco offered an amnesty for most of the refugees except for the murderers. Eventually, the ordinary Spaniards returned.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s Solzhenitsyn and the Right here.

Meanwhile, the rest of Europe collapsed into war. Franco carefully kept out of it although he supported Germany’s campaign against the Soviet Union. The Spanish fielded the Blue Division against the Soviets and sent supplies of tungsten to Germany. However, the Spanish carefully heeded British concerns and returned downed pilots who made it to Spain.

Franco’s forces won in part because they made preserving and protecting Spain’s traditional identity a war aim. Catholicism was to be restored, unity was to be maintained, and slap-dash communist economics was to be ignored. By the end of the 1940s, Franco’s Spain went on to build a genuinely prosperous society. Even in 1948, Franco was looking ahead to what would follow after he died. He put plans in place for the return of the Spanish King as well as the reorganization of the government.

The political problems and social tensions that led to the Spanish Civil War also exist in the Spanish areas of the Americas. In the 1970s, Chile nearly had a Civil War, but it was truncated by swift action by Augusto Pinochet. Undoubtedly, he was greatly aided by advisors from Franco’s Nationalist army. In the 1980s, Central America, especially Nicaragua and El Salvador, suffered from communist incursions. In Cuba, the communists prevailed however, and they still remain, for now at least.

Loveday’s Spain 1923 – 1948 is a great example of a book that cuts through the cacophony of the Leftist narrative that predominates across Western Civilization. Its structure is outstanding, its words are calm and measured, and it is focused on changing the mind of its British target audience. The Infante Don Juan, the son of King Alphonso XVIII and the father of the first King following the restoration of the Spanish monarchy wrote the afterward to the book and he shows how he is connected by blood to the British while still being a proud Spaniard through and through and then he makes a plain and convincing case why the right side won in the Spanish Civil War.