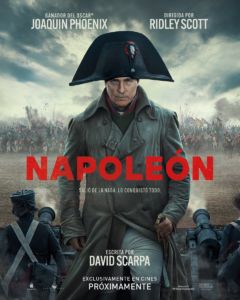

Ridley Scott’s Napoleon

Ridley Scott’s Napoleon is a bad movie, but not a terrible one. There are legions of nerds complaining about how Scott got this or that historical detail wrong. Honestly, that’s beside the point. Even if Scott didn’t know Saint Helena from Elba, he could still have made a great movie.

Everyone has heard of Napoleon. But what’s so great about Napoleon? Any film about Napoleon needs to answer that question. But in nearly three hours’ screen time, Scott fails to do so.

Napoleon rose from obscurity to immense power and world fame. How? On Scott’s telling, he was always an insider, always on the scene, and more powerful people just kept giving him more and more important offices for reasons that remain vague. This is an African’s understanding of how white societies work.

Joaquin Phoenix is a capable actor, but he doesn’t look especially like Napoleon, and he can do nothing with this script. Napoleon summoned forth an immense cult of personality. Phoenix’s Napoleon barely has a personality at all. Phoenix plays Napoleon as a glowering cipher, with all the wit and charisma of a toad. Maybe I just can’t wash Joker out of my memory, but I swear that Phoenix’s Napoleon more resembles one of the madmen who were locked up for thinking they were Napoleon. Indeed, Scott’s Napoleon plays like an unfunny period remake of Jerzy Kosinki’s Being There, about a well-dressed, vacant dullard who bumbles into becoming President of the United States.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

What made Napoleon a great general? How did he command such enormous loyalty? How did he end up being dictator and then Emperor of France? You can bet that the last thing moviegoers today will be shown is why the original Leftist revolution descended into chaos, and why a dictatorship was seen as the best way to restore order.

Scott shows us scenes from history, but not their significance, not the logic of events. If you don’t already know about the French Revolution and Napoleon’s career, most of it will simply make no sense. This spells failure for any historical or biographical drama.

But if you are one of the .001% of moviegoers who already knows the Napoleon story, can you then take some pleasure in Scott’s recreation of scenes from Napoleon’s life? No, because then you are one of the history nerds whom Scott has up in arms, because he just isn’t meticulous enough.

Can Napoleon be enjoyed as a romance? A great deal of the movie deals with Napoleon’s relationship with Joséphine. Neither comes off as particularly loveable, so their relationship is baffling. I don’t know how accurate a depiction it is. I rather hope it was not this sordid and vulgar.

Can Napoleon be enjoyed just as an aesthetic spectacle? Sadly not. Scott decided to wash out the brilliant colors of the clothes, so it doesn’t even work as costume drama. Still, there are a few beautiful touches. The Battle of Austerlitz is a highly aestheticized slaughter. When Napoleon visits the divorced Joséphine to show her his son, we see two swans, who mate for life, drifting apart from one another in the background. But for the most part, Napoleon is a gloomy, muddy, ugly film.

The film ends with a list of the major battles fought by Napoleon, along with the number of dead. Three million people, we are told, lost their lives in Napoleon’s wars. As if he started all of them. As if this is the measure of his life and achievements.

Does Scott’s Napoleon have an agenda? Not really. Aside from shoehorning Africans in the most unlikely places, there’s nothing particularly political about this movie. I don’t think that Scott is trying to bring Napoleon down so much as he just can’t comprehend what made Napoleon interesting in the first place. Hegel once said that “No man is a hero to his valet, not because the hero is not a hero, but because the valet is a valet.” Don’t waste your time with this jumped-up valet’s view of Napoleon.

Hegel dubbed Napoleon the World Spirit on horseback because his victories universalized the idea that all men are free. It would be a sad irony if Napoleon’s victories helped birth a world that can longer comprehend him.