Lebensborn

They never stopped marching, as I like to say. Hardly were German soldiers out of uniform in 1945 than they were marching again — only this time across cinema screens. It certainly cannot be claimed that German post-war film productions did not deal with recent history. The Trümmerfilme, or “rubble films,” a (thankfully!) short-lived genre that I personally admire very much, tell raw stories of their time amidst real ruins and real losses. In 1955 the first of many film adaptations about the July 20 plot, aka the Stauffenberg plot, premiered; at the time it was still a topic of some debate in Germany.

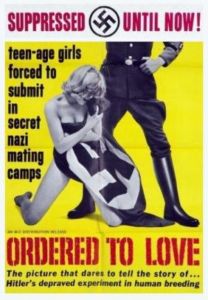

I was intrigued, however, to learn that a film on the Lebensborn program had been released in 1961, an era that generally did not openly delve into sex-related topics in entertainment just yet. The combination of Nazis and sex was certainly unheard of. Not surprisingly, Lebensborn (English title: Ordered to Love) became something of a scandal. The most outspoken and at times hands-on critics of the film’s release were Waffen-SS veterans. Cinema showcases were smashed, and some screenings had to take place under police protection.

The wild legends surrounding the Lebensborn homes had already circulated at the time of their existence, as author Dorothee Schmitz-Köster pointed out in her book Deutsche Mutter, bist du bereit . . .: Alltag im Lebensborn, or German Mother, Are You Ready . . .: Everyday Life in the Lebensborn (my translation):

Even during the Nazi era, there were speculations and rumors about the origins of the Lebensborn children. After all, they were considered “Aryan” through and through, and their parents had been selected according to the “strict hereditary-biological selection principle of the Schutzstaffel,” as a Lebensborn information brochure explained. Didn’t this suggest that the SS also played a role in the creation of these children? . . . The Lebensborn homes must have been “high-end brothels” where the “breeding bulls of the SS” — expressions that were already circulating in the Nazi era — were brought together with selected girls and women in order to produce offspring for the “Aryan elite.”

It has long since been proven that no such practice was carried out in the Lebensborn homes. What made and still makes the idea so attractive that it continues to haunt people’s minds and provokes curious questions? . . .

The image of the black-uniformed men and the blonde girls who produced “Aryan offspring” on command in luxurious houses lives on with astonishing tenacity. Again and again I have experienced men and women holding on to this idea with great vehemence, downright refusing to give it up. Yet the basis of their information and argumentation is often narrow: a novel they read many years ago, an old feature film, a history book that deals with the Lebensborn on half a page. Or a rumor that parents or grandparents told them about . . .

Former Waffen-SS soldier Günter Adam described in his memoirs Ich habe meine Pflicht erfüllt! (I Have Fulfilled My Duty!) an encounter from 1947 with a woman who apparently believed in the stories. It is therefore not surprising that many Waffen-SS veterans did not take too kindly to what must have appeared to them as a perpetuation of dirty old legends.

The film’s plot, however, is slightly different from what might be expected. It does not claim that the alleged practices of pairing Aryan women with SS men, of the “selection of the best blood,” were in any way representative of or a general policy in the Lebensborn homes, but rather a new and scientific approach by an ambitious SS researcher. Thus, the film plays on the prevalent rumors while at the same time avoiding a definite statement — which probably helped with the lawsuits that ensued in the wake of the film’s release.

The film’s plot, however, is slightly different from what might be expected. It does not claim that the alleged practices of pairing Aryan women with SS men, of the “selection of the best blood,” were in any way representative of or a general policy in the Lebensborn homes, but rather a new and scientific approach by an ambitious SS researcher. Thus, the film plays on the prevalent rumors while at the same time avoiding a definite statement — which probably helped with the lawsuits that ensued in the wake of the film’s release.

It is an era that continues to fascinate me. While SS veterans were, on the one hand, the pariahs of German post-war society, they were also an economic force to be reckoned with. Former SS soldiers became businessmen and politicians; they helped build the new German army, the Bundeswehr; and there is even the case of a Waffen-SS veteran who had a successful career in acting: Horst Tappert of Derrick fame. It seems utterly fantastical today that Waffen-SS veterans openly held yearly reunions with large turnouts.

In light of its controversial topic, however, it is not surprising that Lebensborn did not attract many big names among German actors. Sex definitely did not yet sell back then. For example, only a year previously popular actor Karlheinz Böhm had destroyed his career by starring in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom. It’s Lebensborn’s pervading theme of sex — for science’s sake, for the purpose of breeding the perfect race, between consenting partners, between indifferent partners, and even attempted rape — that must have made it quite risqué in its time.

Lebensborn’s opening credits roll dramatically before a background of obituary notices for fallen German soldiers — a silent commentary on the scene we find ourselves in next: A high-ranking SS man gives a pep talk full of patriotic phrases to a group of BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädel, or League of German Girls) members. The young women are asked to give a great and true gift to the Führer — that is, a child. All of them sign on enthusiastically. The project, as it turns out, is the idea of SS race specialist Dr. Hagen, who is very critical of the “normal” Lebensborn policy with its “products of chance.” He instead claims that the whole thing has to be approached scientifically.

After the film’s main female characters are introduced — Doris Korff, a convinced National Socialist and leader of the BDM group; the sexually experienced, sarcastic Erika Meuring; and Lotte Wieland, at 17 the youngest girl of the group — the story then switches to the primary male protagonist. Klaus Steinbach of the Luftwaffe is stationed in occupied Poland and comes across a reprisal action by German soldiers in some village. The blond children, Steinbach learns, are to be taken to a Lebensborn home in order to save their “buried Germanic heritage.” The officer in charge despises Steinbach just as much as Steinbach despises him due to the fact that the “cavaliers” of the Luftwaffe fight their war far above the dirty realities of land warfare. (In fact, German pilots had a strict chivalric code of honor; read all about it in Adam Makos’ A Higher Call.) As Steinbach drives away in his car, he hears shots behind him as the villagers are being executed.

Back at the barracks, Steinbach learns that one of his colleagues, Helmut Adameit, has been chosen for a “biological training course” at the Lebensborn, much to the amusement of his fellow pilots. Frustrated by what he just witnessed, Steinbach makes some unwise remarks about the conduct of the war and the political system, which prompt Adameit to report him. When Steinbach’s diary is found with even more unwise remarks in it, he is arrested and put on the same transport that is to bring Adameit to the nearest town. As fate would have it, partisans attack the car. In the ensuing firefight, Adameit is killed, and Steinbach’s friend Mertens urges him to switch identities with the dead man.

In the meantime, the young women have arrived at the Lebensborn home and have their physical examinations. Dr. Hagen, who of course turns out to be not quite as scientific as he claims where his personal interests are concerned, takes on Doris as his assistant. One girl is sent home because of tonsillitis; Erika, true to form, recommends that she find herself a guy who doesn’t care about her tonsils. She also mocks young Lotte, who has no sexual experience at all but who has a rather romantic outlook on life.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

She is not alone in that, as we learn when the men arrive. Erich Gühne, a young pilot, dreams of finding true love, and sure enough the two of them take an instant liking to one another. Theirs is easily the most relatable relationship in the film, a sweet first love — which makes its brutal end all the more impactful.

Erika hits it off with an irreverent officer of the Panzer Corps, Otto Kempe. Strangely, the credits list his rank as Hauptsturmführer, which would make him a captain of the Waffen-SS, yet the dialogue repeatedly stresses that he is not SS. I don’t know who slipped up here. Was he originally meant to be of the Waffen-SS, and somebody decided that was not appropriate for one of the good guys? At any rate, Erika and Otto are the film’s fun couple and comic relief.

Late to the party thanks to the partisan attack is “Helmut Adameit,” aka Klaus Steinbach. Doris is quick to notice several discrepancies in his story and medical record. When she observes him ripping out the photos of himself and Adameit in a book about decorated soldiers, she checks another copy, and of course immediately learns of his real identity. Taken to task, Klaus explains why he did what he did. He isn’t disparaging the fighting men, he assures her, but rather what goes on behind their backs: the war on civilians.

Doris’ naïve belief in the nobility of her cause is somewhat shaken, but it takes the truth about the experiment for her to rebel. Dr. Hagen, who eyes the burgeoning love affair between Doris and Klaus with suspicion and jealousy, reveals that the young women are being paired up with a man chosen for them according to Hagen’s “Germano-biological coefficient.” This comes as a bit of a shock for both groups and stirs resentment — but, as they are reminded, they are under orders.

During the solstice celebration, the pairings are announced. Tragedy strikes when Lotte and Erich are not chosen for one another, driving home the cruelty and plain stupidity of the experiment. Faced with rape, Lotte jumps out of a window and kills herself. In the confusion, Klaus, whose cover has been getting thinner by the day, tries to escape to neutral Sweden with Doris, who has become his lover at this point. But there will be no happy ending for them, either: He is shot, and then she is sent to prison and saved from execution only by the approaching front. But her child, born in prison and immediately brought to the Lebensborn home, is lost in the chaos of the war’s end. When Doris passes a refugee caravan that has been strafed by Soviet fighter planes, she finds a surviving child whom she takes in.

Lebensborn is very much a product of its time, and I don’t only mean the early 1960s haircuts that irritate me more than they probably should. It manages that balancing act between a condemnation of National Socialism as a political system on the one hand and showing an understanding of the ordinary people living under that system on the other. There are very few bad guys, even among the SS and diehard National Socialists. They might be misguided and ignorant, but they seldom act with evil intent. There is also no mention of Jews.

The characters represent a broad range of personalities: the frontline soldiers who are a far cry from taking the whole project seriously; the BDM volunteers who range from straight-laced to downright saucy; the scientist with his strictly mathematical approach unless it is to his own advantage not to be; the SS observer who is proud of the decent and splendid men under his command. I was also really impressed with all the little things that are spot-on about Nazi Germany; clearly, the producers and older actors remembered the real thing in order to get it right like that.

Attempting to cash in twice, screenwriter Will Berthold published a novel called Der Lebensborn e. V. in 1975 that basically tells the same story, albeit with a few minor changes.

In subsequent years a few other films picked up the topic, most of them simply going with the old “breeding the master race” angle. One example is the American film Of Pure Blood (1986), inspired by the book Au nom de la race (Of Pure Blood/Children of the SS) by French authors Marc Hillel and Clarissa Henry. Dorothee Schmitz-Köster, while acknowledging their work as being in many ways groundbreaking, was critical of their research methods:

The two French journalists also obviously had an image in mind when they began their investigation: the image of the black-uniformed men and the blonde girls who produced “Aryan” offspring in Lebensborn homes. They tried to substantiate this image by reinterpreting the term “nurse,” by turning ambiguous witnesses into key witnesses, and by discovering alleged crime scenes everywhere. Thus, their work once again perpetuated the Lebensborn image that had already been disseminated for years through rumors, the entertainment industry, and the press.

While the film Of Pure Blood is full of improbabilities and clichés, it is surprisingly strong in its portrayal of its female characters. Despite all the suspense and intrigue, it is at its core a story about mothers.