Once Upon a Time in the West, Part 2

After the climactic gunfight between Frank and Harmonica, the latter and Cheyenne say goodbye to Jill. But just outside of the McBain property, Cheyenne falters. Harmonica stops and turns with concern. It turns out that Cheyenne was mortally wounded by Morton. Like Jesus, he has a bleeding wound in his side. This comes as some surprise. He must have been putting up a brave front with Jill. But the surprise comes off as a rather contrived plot twist; one of many. Cheyenne doesn’t want Harmonica to watch him die. But the men are friends now, friends to the end, and what’s a little death between friends? When Cheyenne expires, Harmonica loads his body onto his horse. They head west, of course, beyond where the rails have stopped, into the wild. Jill, in the meantime, brings water to the railroad workers who have brought civilization to her doorstep. The end.

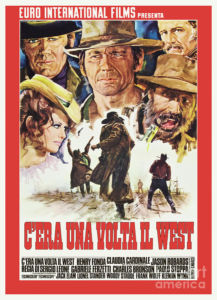

There are many great things about Once Upon a Time in the West: a beautiful script, inspired direction, vivid cinematography, meticulously detailed and authentic costumes and sets, and superb performances, especially from Henry Fonda and Jason Robards. Ennio Morricone’s magnificent music deserves special mention. Half the emotional impact of the film comes from the music alone.

But be warned: the plot is often a mess, which is hard to forgive in a film that runs nearly three hours. I have already dwelt upon the film’s second act. But there’s a lot that makes no sense in the rest of the film as well.

When Cheyenne is first introduced at a ramshackle dive in the desert — What is it, anyway? A bar? An inn? A stable? Does a cyclops live there? — his behavior is so bizarre and menacing that any number of people would be tempted to shoot him dead in self-defense. But all he wants is someone to break the chains on his wrists.

Later, when Cheyenne visits Jill, he is again so menacing that she is tempted to kill him. Yet he is there to declare his innocence and offer his protection. I get it. He’s a man of few words. So why doesn’t he choose them more carefully? One feels here that Leone is just jerking you around, building up false suspense.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here

Harmonica camps out at the McBain house to protect Jill, but he does not knock at the door and introduce himself. He starts playing the harmonica in the dead of night. Jill thinks he is a bandit and tries to shoot him. It is a natural reaction. Her whole family has just been killed.

The next day, when Jill and Harmonica meet by daylight, he does not greet her politely, exchange names, and explain he is there to protect her. Instead, he throws her around, roughs her up, and tears her clothes as if he is about to rape her. Is this his idea of an acceptable greeting? Does he play the harmonica rather than talk because he’s autistic? Then Harmonica abruptly breaks off the assault and asks Jill to get him water from the well, at which point two of Frank’s men gallop up to kill her, and Harmonica guns them down. Again, is there a point to this bizarre behavior, or is Leone just jerking us around?

When Frank returns to Morton’s train to find the results of a massacre, we are left to wonder who these men were and what happened. Later, we learn that Cheyenne led that raid. But why? Was it to take revenge on Morton? I guess that makes sense.

I think it is important to lay all of this film’s flaws on the table, because the payoff in the end is worth waiting through them.

Leone’s early films are perfect, but not particularly moving, because they aren’t particularly deep. The conflicts are merely about money, not principle. In Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone stirs us more deeply because this is not just a movie about men; it is a movie about ideas, about the principles from which different lives and different civilizations spring.

The Western lends itself to political philosophy because on the frontier, one leaves behind civil society and enters a state of nature, thus highlighting the distinction between nature and convention.

The frontier is also a realm of clashing tribes — white, Indian, and Mexican — thus highlighting race, identity, and enmity as political forces.

The frontier also stimulates the re-emergence of archaic values such as the honor code and archaic institutions like the Männerbund, prompting reflections on how these can be integrated into civilized society, if at all.

The frontier is a realm of freedom and adventure, which are especially bracing to men. Can this freedom be preserved under law and civilization?

Finally, the frontier is a dangerous place. It selects for strength, vitality, and masculinity, posing the question of whether these can find a place in civil society.

Or will it always be the case that hard times produce strong men, strong men produce easy times, easy times produce weak men, and we are doomed to hard times again?

What is the politics of Once Upon a Time in the West? The film is clearly anti-capitalist. But is it anti-capitalism of the Left or of the Right? There is not a word about inequality or exploitation in this film, which counts against any sort of Leftist interpretation. The primary victims are not the proletariat, but the McBain family, who are landholders seeking to get rich from a railroad concession.

The central contrast of the film is between man and businessman, not capitalist and proletarian. The “ancient race” that the Mortons of the world wish to kill is not the proletariat. It is not colored people. It is men of honor, men who prize honor over life itself. This is the pre-modern, aristocratic ethos. These are the men of “pride and vainglory,” the “contentious and quarrelsome” whom Thomas Hobbes and John Locke wished to replace with the rule of the “industrious and rational.” Thus, Once Upon a Time in the West offers a critique of capitalism from the Right.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

I argue that Once Upon a Time in the West is objectively Rightist, even though this was not the filmmakers’ intention. Leone himself had fashionably Leftish ideas. Bernardo Bertolucci, who co-authored the original story with Leone and Dario Argento, was an avowed Marxist. Yet there is nothing Marxist about Once Upon a Time in the West. (Nor is there anything Marxist about his greatest movie, The Last Emperor, which I review here; it is also included in Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema.) The fact that Once Upon a Time in the West was hugely popular among the Parisian student Leftists of 1968, who were crazy about the movie’s long “duster” coats, proves nothing, either. These kids had great taste in film and fashion, but they were too poorly educated to understand what they were seeing.

Hegel held that the duel to the death over honor was the beginning of man and the beginning of history. Before the duel, men were just clever animals ruled by natural desires, above all self-preservation. By subordinating life itself to the imagination — specifically one’s image of oneself — man created the realm of history and culture, which is defined as going against nature. Hegel saw history as a struggle for self-consciousness, which would end when men have realized that we are all free and have built a society that expresses that truth. But Hegel’s critics from the Right realized that if making history makes us human, the end of history will be the end of man, the return of merely the cleverest animal.

Once Upon a Time in the West ends by showing us the beginning of history reenacted in the showdown between Frank and Harmonica just as the end of history is pulling into town on Morton’s gleaming rails. What do our heroes do? They head west.

We should follow.

It is one thing to write about such ideas, another thing to show them. That’s why the end of Once Upon a Time in the West feels less like a movie, and more like an initiation into some great mystery: why we rise, why we fall, and why there’s no stilling or stepping off the great wheel of time.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.