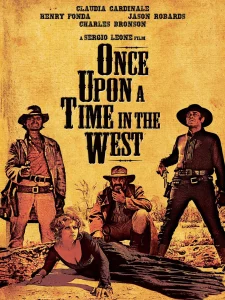

Once Upon a Time in the West, Part 1

Part 1 of 2

I have had a difficult relationship with Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Parts of this film are so emotionally powerful as to be almost endurable. Indeed, before I began work on this review, I had seen Once Upon a Time in the West only one time in full, on a rented VHS tape in the 1990s. I knew it was a great film, so I bought the VHS. But I could not bring myself to watch it again. Then I replaced the tape with a DVD, but I could not bring myself to watch it in the new format, either. Eventually, I sold my unwatched DVD and bought a BluRay. But more than five years passed, and I still could not bring myself to watch it. Finally, before I faced the absurdity of buying the film again in 4K, I forced myself to watch it by agreeing to discuss it on Fróði Midjord’s Decameron Film Festival.

After more than 30 years, I was surprised at how much I remembered. Whole sequences were simply seared into my memory. Even though I knew what was coming, the emotional impact was not dulled in the least. The only surprise was that the film’s dramatic flaws seemed quite glaring. This is a great film, but it could have been so much better.

In some ways Once Upon a Time in the West is less successful than Leone’s first three Westerns: A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966), which are nearly perfect movies but not particularly deep ones. Once Upon a Time in the West, however, is imperfect because it tries — sometimes fumblingly, but usually successfully — to be deep.

Once Upon a Time in the West, like many classic Westerns, is constructed around the contrast between the “wild West” and the creeping civilization which followed the pioneers, pushing back the frontiers until they disappeared. The film is also constructed around a related distinction between the man and the businessman.

Near the end of the film, we have the following dialogue between the two central characters, Frank, a hired killer played by Henry Fonda, and Harmonica, a mysterious gunman who is pursuing Frank, played by Charles Bronson:

Frank: “Morton once told me I could never be like him. Now I understand why. Wouldn’t have bothered him, knowing you were around somewhere, alive.”

Harmonica: “So you found out you’re not a businessman after all.”

Frank: “Just a man.”

Harmonica: “An ancient race. Other Mortons will be along, and they’ll kill it off.”

Frank: “The future don’t matter to us. Nothing matters now. Not the land. Not the money. Not the woman. I came here to see you. ’Cause I know that now you’ll tell me what you’re after.”

Harmonica: “Only at the point of dying.”

Frank: “I know.”

Morton is a railroad tycoon who hired Frank to occasionally intimidate or kill people who got in the way of progress. Morton would not be “bothered” by Harmonica, because Morton is not fundamentally motivated by honor. Morton has been crippled by creeping tuberculosis of the bones, a degradation that Frank thinks a normal man would cast off with a bullet to his brain.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

Frank is willing to cast off his life to preserve his honor, but Morton wishes to prolong his life at the expense of honor because he has a dream: building a railroad that reaches the Pacific, which of course would spell the end of the frontier.

Morton loves money. He lives in a luxuriously-appointed private train and throws a great deal of cash around. But ultimately his money is in the service of a very Faustian dream: progress, Manifest Destiny, gleaming rails from sea to shining sea. But for all that, he is still spiritually bourgeois, because he places life above honor.

Frank is not just a cold-blooded killer of women and children, he is also a sadist. Beyond that, he kills for money. Yet, Frank puts honor above life. He would rather die than exist in Morton’s condition. He is also “bothered” by Harmonica enough to seek him out and put his life on the line in a gunfight. Harmonica has bothered Frank in two ways: He has offended his pride, and he has piqued his curiosity. Frank is willing to risk death not just over honor, but also truth.

Once Upon a Time in the West begins with a brilliant opening sequence. Three gunmen arrive at a ramshackle station to wait for a train. The gunmen are outlaws, men of the wild West. The train represents civilization. Wherever the tracks extend, the frontier and its wildness end. The geezer who mans the station is decrepit, chatty, and ingratiating. Like Morton, he is the kind of man who would be dead on the frontier, but the railroad enables him to live on. The gunmen, by contrast, are tough, taciturn, and utterly contemptuous of the old man. They don’t waste a single word on him.

Everything about the station seems designed to annoy the gunmen: the squeaking of the windmill, the chattering of the telegraph. Leone uses these sounds, as well as long silences, to build enormous tension and suspense, until finally there is an explosion of violence.

The feel of the sequence is epic, Homeric. It is an encounter between vital barbarism and the first probing fingers of decadent civilization.

The gunmen don’t wish to travel. They are a welcoming party. Their boss, Frank, has sent them to kill a man who made an appointment to meet him. The man turns out to be Harmonica, who is called that because it seems he’d rather play a harmonica than talk. He is the most laconic frontiersman of the lot. Harmonica can also shoot. When he sees that Frank has sent men to kill him, he guns them down effortlessly.

In the next sequence we meet Frank, as he and his henchmen murder an entire family, the McBains: the father and his three children. Their mother is already dead. It is a brutal and shocking sequence, culminating with Ennio Morricone’s magnificent “Man with a Harmonica” theme, which associates the harmonica with Frank, not just the Harmonica character. We learn why near the end of the film.

Unbeknownst to Frank, there is a new Mrs. McBain, Jill, played by Claudia Cardinale, who arrives the very day of the massacre to find her husband and stepchildren dead. It is a touching sequence, but Jill’s reaction seems a bit cool. Maybe she’s just stoic. But a question hangs over the character that will later be resolved.

Morton, played by the great Italian actor Gabriele Ferzetti, is introduced as a grasping hand. His fist closes over the figure of a conquistador, pulling it back to reveal a model train bearing his name. As Morton yanks the conquistador out of the frame, he scolds his own conquistador, Frank, for the senseless murder of the McBains: “You were only supposed to scare them!” Morton values human life, especially his own, but also the lives of others. For Frank, however, life is cheap, even his own.

Frank has framed another outlaw, Cheyenne — played by Jason Robards — for the murder of the McBains. Cheyenne shows up at the McBain house to speak to Jill because he wants to clear his name and learn why the family was murdered. Harmonica is pretty sure that Frank is behind the massacre, but he doesn’t know why. Soon, Cheyenne, Harmonica, and Jill team up to solve the mystery.

Once Upon a Time in the West falls into roughly three acts. The first and third acts are slow-moving, pithy, epic in feel, and sometimes emotionally shattering. The second act is fast-moving, with jarring cuts. It is also chatty, petty, and farcical. Dramatically, it is the weakest part of the film.

The second act commences with a great pile of lumber. Brett McBain has ordered enough lumber to build a small town. But why? Suddenly, Harmonica reveals the answer. A contract is introduced as a deus ex machina: McBain’s land has plentiful water in the midst of the desert. Morton’s railroad needs that water. McBain will have the right to build a town there, as long as a station is built by the time the tracks reach it. The tracks are almost there, so Cheyenne orders his outlaw Männerbund to start building a station. Cheyenne and Harmonica suddenly seem interested in striking it rich. It is a jarring change of character.

In the meantime, Frank has kidnapped Jill, and Jill has seduced Frank. It is a cold turn for a grieving widow, but we learn that Jill is a former prostitute. She’s a businessman, too, like Morton. Frank contemplates forcing Jill to marry him so he can own her land. She would go along with that to save her own skin. But instead, Frank decides to force her to auction the land, dispatching his gang to intimidate other bidders so that one of Frank’s proxies can pick up the land for cheap. Harmonica spoils the plan by bidding $5,000, a handsome sum. Where does Harmonica get the money? By turning in the outlaw Cheyenne for a $5,000 bounty. It is utterly farcical. Is Cheyenne so smitten with Jill that he would risk his life to save her land?

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Part Four of the Trilogy here.

The act ends as Jill goes off to take a bubble bath and Frank shows up to make Harmonica an offer he can’t refuse for the land: $5,000 plus a silver dollar, because “Everyone has the right to make a profit.” Harmonica drops the silver dollar in an empty glass to pay for his whiskey, leaves the $5,000 on the table, then walks away. This opens act three with a return to the heroic world.

The most charitable interpretation of Act Two is that it is there to make us heartily sick of Morton’s civilization. It is a world of laws, contracts, and business. It is also a woman-centered world. Suddenly two outlaws and an outlaw gang are orbiting an ex-prostitute to help her get rich. Finally, it is the world of Christianity, for when Cheyenne is turned over, he says that Judas settled for 4,970 fewer pieces of silver. But Cheyenne is not sacrificing himself to redeem humanity, but merely the widow McBain’s farm.

Harmonica bothers Frank because he has dogged him relentlessly without saying who he is or why he is doing it. When Frank asks for his name, Harmonica merely responds with the names of men Frank has killed. Harmonica has also killed five of Frank’s men. Now he has refused Frank’s offer for the land. But to add insult to injury, Harmonica then saves Frank from some of Frank’s own men who are waiting to kill him as he leaves. Morton fears Frank and has paid his own gang to kill him. Frank rides off to Morton’s train, only to find half-a-dozen dead bodies and Morton dying face down in a mud puddle.

Meanwhile, back at the McBain property, Jill watches the completion of the station as the first train arrives. Harmonica is whittling on a piece of wood, waiting. Cheyenne shows up, having escaped from the law. Jill fully expects both men to try to marry her. But then we learn, no, that’s not what either of them had in mind. It wasn’t about Jill at all. Both outlaws were simply after revenge. Jill has gotten what she wants, but not Cheyenne and Harmonica. We later learn that Cheyenne killed Morton, but Frank is still at large.

Cheyenne tells Jill that she doesn’t understand men like Harmonica: “People like that have something inside. Something to do with death.” This is true of Cheyenne as well. This thing to do with death is the wild West’s honor code. Honor comes before all else. Frank speaks for them all at the end. For this kind of man, when honor is at stake, “The future don’t matter to us. Nothing matters now. Not the land. Not the money. Not the woman.” And not life itself. The shootout between Frank and Harmonica is one of the most emotionally shattering climaxes in all of cinema. I’ll not spoil it with words. It must simply be seen and heard.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.