Plastic Patriotism: Propaganda and the Establishment’s Crusade Against Germany and German-Americans During the First World War

Erik Kirschbaum

Burning Beethoven: The Eradication of German Culture in the United States during World War I

New York: Berlinica Publishing, 2014

Much ink has been spilled over the travails faced by non-white minorities in the United States, but the persecution of German-Americans during the First World War has received scant attention. The few scholars who do address this forgotten chapter in American history, such as Erik Kirschbaum in Burning Beethoven, frame it as a morality tale about the evils of “xenophobia” and cast WASP Americans as the villains. But the real lesson here is that the mainstream media and the British propaganda machine brainwashed white Americans using sound patriotic instincts into turning against their racially similar countrymen and supporting a war in which millions of young white men were killed at the altar of international finance.

It is hard to exaggerate Americans’ animosity towards Germany during the First World War. Anything remotely connected to Germany was regarded with suspicion at best, if not outright targeted for destruction. Thousands of German-American men were arrested and sent to internment camps, where they did forced labor. German-Americans deemed insufficiently patriotic were tarred and feathered, or even lynched, by violent mobs. Dachshunds were referred to as “liberty hounds” (there were even cases in which dachshunds were killed) and hamburgers as “liberty sandwiches.” German-language books were banned and were destroyed in public book burnings. Most German-language newspapers went out of business. Pittsburgh enacted a city-wide ban on Beethoven, and the Metropolitan Opera and the Philadelphia Orchestra stopped programming German composers. Conductors Frederick A. Stock, Karl Muck, and Ernst Kunwald were sent to internment camps.

German-Americans had been respected for their contributions to American culture prior to the First World War. They occupied prominent positions in politics, the arts and sciences, and industry. They were at the center of American musical life and introduced the sport of gymnastics to the United States. They also considered themselves to be Americans. About 450,000 German-Americans fought in the Civil War. A popular saying among German-Americans was Deutschland meine Mutter, Amerika meine Frau (“Germany my mother, America my wife”). The relationship between Germany and the United States was one of goodwill. For instance, in 1902 Kaiser Wilhelm II made a pledge to Harvard’s Germanic Museum, which was the first museum in North America dedicated to the countries of Central and Northern Europe. Harvard had also been influenced by the German university system in the 1860s.

German-Americans were reluctant to go to war with Germany, for which they were accused of being disloyal and unpatriotic. They were often falsely accused of being spies. Theodore Roosevelt, a vocal critic of “hyphenated Americanism,” saw German-Americans’ commitment to neutrality as an indication of their failure to assimilate and warned that that the country would perish if it became a “tangle of squabbling nationalities” (p. 123). He was correct that linguistic and cultural diversity as well as Old World feuds posed a danger to national unity, but his characterization of anything short of eagerness to slaughter one’s own ethnic kin as a form of treason is uncharitable. Our identity as white Americans should trump our ethnic heritage, but it is possible to acknowledge and be favorably disposed towards our European roots while remaining patriotic Americans.

German-Americans’ ultimate allegiance was to the United States, and they vowed to fight for it in the event of a war. Kirschbaum cites German-American historian Carl Wittke’s findings that after the Zimmermann telegram came to light, German-American newspapers had “a clear pro-American stance,” and that by the summer of 1917 they were virtually unanimous in their support for the United States (p. 136). In a similar vein, East Coast elites admonished the Western states for being “unpatriotic” and insufficiently enthusiastic about the war, but Westerners were in fact more likely to enlist in the army.[1]

In other words, the campaign against German-Americans was spurious and ill-founded. It was far from a benign attempt to promote national cohesion and assimilation, which would have happened regardless; it was an attack on Germans specifically. While wartime propaganda warned of a fifth column of German-American spies, the influx of Jewish immigrants remained unchecked. Over the course of the 1910s, German-language newspapers all but disappeared. Meanwhile, Yiddish-language newspapers ballooned from eight publications and 321,000 readers to 23 publications and 808,000 readers.

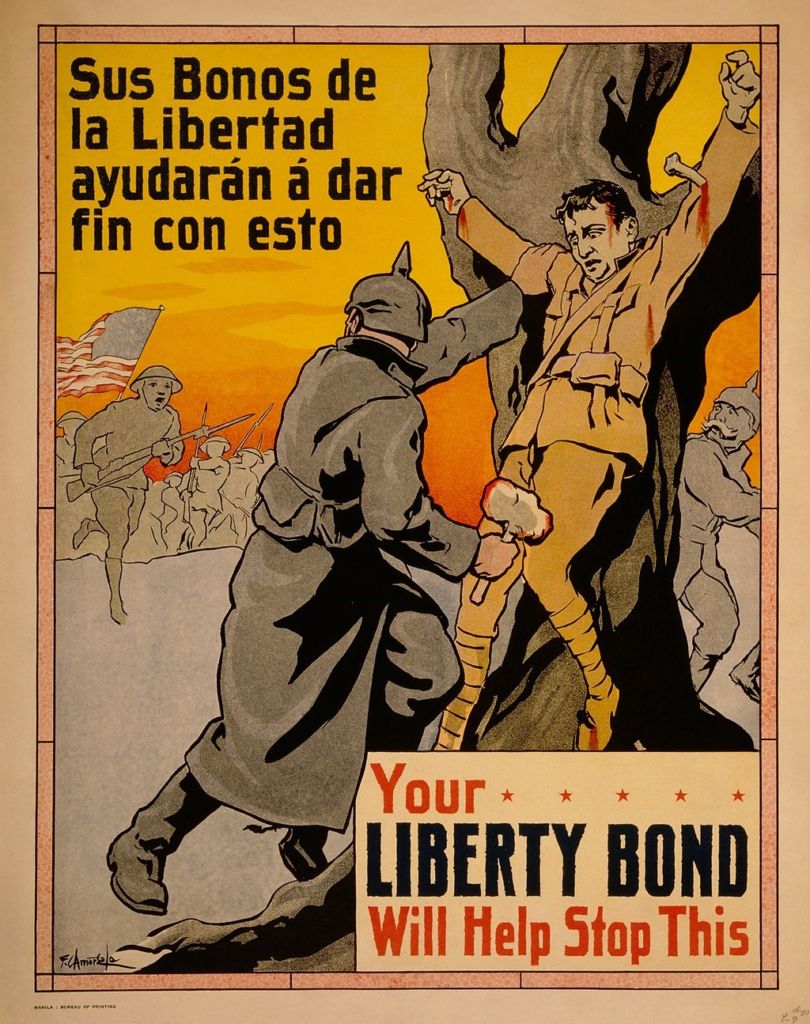

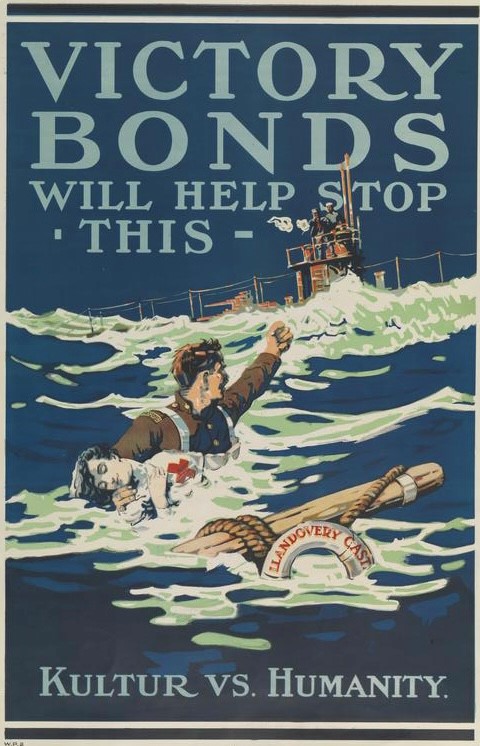

Americans’ crusade against anything German was informed in large part by British propaganda. British agents cut off Germany’s transatlantic line of communication with the United States, so Americans received all their news about the war solely from Britain. Following Germany’s invasion of Belgium, Britain’s War Propaganda Bureau — also known as Wellington House — and the British press churned out graphic accounts of German soldiers raping and dismembering women and children. Civilians were indeed killed during the invasion of Belgium, but the lurid reports of German soldiers’ sadism were fabrications. According to a New York Times correspondent who went to Belgium to investigate the matter, “None of the rumors of wanton killings and torture could be verified” (p. 73).

The scale of Britain’s propaganda effort “dwarf[ed] everything seen before” (p. 69). Wellington House enlisted leading British writers to write books and pamphlets that would advance the government’s agenda. Britain also released several propaganda films. The newspaper publisher Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express, deserves special mention for his role in devising new forms of propaganda. The primary purpose of British propaganda was to sway popular opinion among Americans and galvanize the United States into entering the war.

Britain was far more ruthless than Germany. Britain’s attitude toward the Germans is best encapsulated by the Bishop of London’s injunction for Brits to

kill the good [Germans] as well as the bad, to kill the young men as well as the old, to kill those who have showed kindness to our wounded as well as those fiends who crucified the Canadian sergeant, who superintended the Armenian massacres, who sank the Lusitania . . . and to kill them lest civilization of the world should itself be killed.[2]

The alleged gory crucifixion of a Canadian soldier who was said to have been nailed with bayonets to a barn door or tree by the Germans was another tall tale invented by British propagandists.

Kaiser Wilhelm II was likewise caricatured as a bellicose dictator. The 1918 silent film The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin depicts him as arrogant and power-hungry. Winston Churchill described him as a “tyrant” whose goal was “the dominion of the world.”[3] But he had not wanted war and had never fought a war during his previous 25 years on the throne. His creation of Germany’s High Sea’s Fleet was a political blunder, but it was a defensive measure intended to protect the North Sea and Baltic coasts and mitigate the threat posed by the Royal Navy. Churchill himself even admitted later in life that “history should incline to the more charitable view and acquit William II of having planned and plotted the World War.”[4]

Germany’s use of U-Boats was likewise an act of self-defense intended to undermine the British naval blockade that restricted the flow of goods to the Central Powers and, in the early years of the war, was limited so as not to provoke the United States. The sinking of the Lusitania by a German U-Boat was frequently portrayed at the time as an example of German aggression and barbarism, but Germany was in fact so keen to avoid war that the German Embassy placed advertisements in American newspapers warning American citizens not to travel on British ships. Moreover, the Lusitania had been carrying ammunition, empty shell cases, artillery fuses, and aluminum powder. Kirschbaum does not discuss the long-standing theory that the sinking of the Lusitania was deliberately facilitated by the British authorities in order to provoke the United States into entering the war, but it is a real possibility.

It is noteworthy that Kirschbaum discusses much of the above and paints Germany in a sympathetic light. He even briefly touches on the role of the munitions lobby and international finance in embroiling the United States in the First World War:

[T]he U.S. government had no desire to limit weapons trade, as the war in Europe had stimulated urgently needed U.S. economic growth. The United States did not want to let a simple detail like neutrality get in the way of its business interests. (p. 84)

The role of Wall Street in financing and prolonging the war merits its own essay, but suffice it to say that bankers played a significant role in strengthening the Triple Entente and profited from the war, as did the thousands of wealthy Americans associated with the East Coast establishment who had invested in loans to the Allies. J. P. Morgan, Jr., who had close ties to the British government and the Rothschild family, lent $500 million to the Allies. He was Britain’s sole purchasing agent and monopolized transatlantic shipping via the International Mercantile Marine Company.

According to Franz von Papen, Morgan appointed English editorial writers to 40 American newspapers in an attempt to spread British propaganda and sway public opinion.[5] This made it doubly ironic that the American press framed support for the war as “patriotic”: Not only did the war not serve American interests, but many of the journalists influencing public opinion were not even American. It brings to mind the phenomenon of contemporary non-white journalists deriding opposition to immigration as “un-American.” They do not care about America, and only invoke patriotism because they know that white Americans are loyal to the flag.

Of course, Burning Beethoven’s frankness regarding Anglo-American warmongering is overshadowed by its over-arching message about the folly of discrimination and prejudice. Kirschbaum compares the persecution of German-Americans during the First World War to Americans’ hostile attitudes toward Muslims after 9/11, and states that his aim in writing the book was to help prevent future instances of discrimination.

The parallel Kirschbaum draws between the treatment of German-Americans during the First World War and Muslims after 9/11 is genuinely instructive, though not in the way he intended. Americans’ animosity toward Muslims was fomented by the media in order to distract the general public from Israel’s complicity in 9/11. Neoconservative politicians galvanized the American public into supporting an unnecessary foreign war under false pretenses (“weapons of mass destruction”) by invoking “patriotism.” In both cases, a false enemy was propped up to serve as an outlet for white Americans’ patriotism and distract them from what was actually happening. Muslims certainly are not our friends, but they have never been white Americans’ primary enemy, either.

One of the main functions of the Conservative, Inc. media ecosystem is to generate interest in GOP-approved politicians and peripheral issues such as abortion while funneling white Americans’ political energies away from white identity politics. There is a temptation for White Nationalists to jump on these bandwagons and allow ourselves to be swept up in mainstream conservative fads, because it provides the satisfaction of feeling that one is no longer on the margins. We may even delude ourselves into thinking that we are furthering our goals by doing this. But more often than not, it merely drains the movement of time and resources.

Anti-German warmongers appealed to reasonable Right-wing sentiments: They spoke of the importance of national unity, loyalty to one’s country, and a common culture and language. This rhetoric undoubtedly ensnared many sensible Americans who otherwise might have been less inclined to support the war.

Ordinary white Americans were not the villains during the First World War or the “war on terror.” They had no way of knowing that they were being lied to by politicians and the mainstream media. The real villains are the leaders who orchestrated these conflicts and who continue to attempt to brainwash white Americans into abandoning their racial and national interests under the guise of patriotism.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Jim Macgregor & Gerry Docherty, Prolonging the Agony: How the Anglo-American Establishment Deliberately Extended World War I by Three-and-a-Half Years (Walterville, Or.: TrineDay, 2017), p. 397.

[2] Ibid., p. 54.

[3] Patrick Buchanan, Hitler, Churchill, and the Unnecessary War (New York: Random House, 2008), p. 57.

[4] Ibid., p. 57.

[5] Macgregor & Docherty, p. 46.