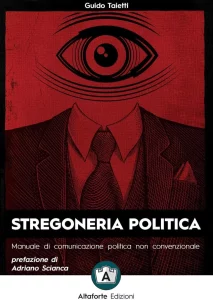

There Is a Political Solution: A Review of Guido Taietti’s Political Witchcraft

Stregoneria Politica is the title of Guido Taietti’s “manual of non-conventional political communication.” It translates as “political witchcraft,” and one can see why such a title was chosen. There may be nothing new under the Sun, and doing politics has always been a messy business no matter which system of government was employed, but the advent of the Internet and social media has rendered the political realm today even more bewildering, heaving with with a multitude of parties and actors who are all noisily vying for attention. How can a small political operation, such as a nationalist movement, make sense of this weird world and come to use this “witchcraft” for its own purposes? Taietti’s book aims to help.

Guido Taietti has been involved in Right-wing Italian activism for nearly two decades and holds a Master’s degree in Political Communication from the University of Florence. Naturally, his book is filled with references to and anecdotes about Italian politics and Italian history, but this does not mean it’s a book that is only for players on the Italian political chessboard. Almost everything Taietti addresses, as well as his advice regarding strategy and tactics, is relevant to anyone, anywhere. In particular, “Right-wingers” in the Anglosphere could benefit immensely from being introduced to some of Taietti’s concepts.

One of the pillars of Taietti’s thesis is that the “Right” must be radical. It must be revolutionary. He is adamant that the encroachment of “conservatism” into Right-wing politics in Italy has had a pernicious effect. In Italy there is a fairly solid foundation of genuine third positionism, nationalism, and anti-establishment sentiment. However, Anglo-Saxon style conservatism has been seeping into the Italian soil of late and causing significant harm. For Taietti, conservatism is almost indistinguishable from the liberalism it purports to oppose.

The liberals are in favor of mass immigration for moral reasons, such as improving the lives of Third World peoples by letting them live in the First World, and ending racism by creating multi-racial societies where everyone gets along happily. The conservatives are in favor of mass immigration for economic reasons. So long as the migrants come “legally,” the conservatives don’t have any objections. This has been made crystal clear by Giorgia Meloni’s government and her new stance on immigration. In order to fill in “gaps in the labor market,” Meloni’s so-called far-Right government has drawn up plans to take in 450,000 non-European Union migrants in the coming years. Of course, given that these migrants can and will demand that their families be allowed to tag along, the real number of foreigners Meloni is prepared to let into Italy is actually closer to a million. We know from experience that these migrant workers and their families won’t pack their bags and go back home when the jobs they’ve been brought in to do are finished. They come to stay.

Meloni used the migrant invasion of Italy to stoke support for her campaign, and in typical conservative fashion she focused on family and Catholic values, and this was enough to be labelled “far Right” by the mainstream media. But she is no radical revolutionary. We see the same trick play out in the United States and in other countries in Europe. Conservatives ultimately serve the establishment and the status quo. This why Taietti recommends that the “real” Right stop thinking and acting like conservatives.

Forming a Guerilla Army

What should the radical right do? According to Taietti, “the base of non-conventional political communication is the construction of an army of soldiers who know how to fight by themselves . . . who attack at every opportunity.” Taeitti sees four categories of political man:

- The consumatore. The voter, or “consumer.” This is the politically passive citizen who makes decisions based on one or two issues and votes for the party that “feels right” based on how it relates to those issues. We might call him a “normie.”

- The simpatizzante. This is the “supporter,” or “fan.” He does the bare minimum in terms of active political participation, but at he least he does participate. He shares a post or an article in support of a party. He has certain political or ideological preferences and is able to defend them.

- The militante. The best translation of militante is “activist.” These are the people who reach the highest level of active political participation. They don’t merely share posts or articles, but also make their own. They know the party’s positions and know how to argue for them and defend them against critics.

- The party member/party leader. These are similar to the militante in capacity, with the difference that the party member is usually interested in having a career in politics and is more willing to be loyal to a party in spite of setbacks or contradictions. Crucially, this figure is not always necessary and can even be harmful for a small political organization that is outside the mainstream.

For radical and dissident groups — CasaPound Italia, for example — the militante plays the most important role. Taietti draws frequent comparisons to military operations. The mainstream political parties are like a grand imperial army. They have money and resources. They have ranks and divisions: infantrymen, cavalry, medics, scouts, engineers, generals, captains, etc. The small political actor is more like a guerilla army. Taietti compares dissidents to guerilla warriors fighting in the jungle. Each militante must be a soldier, but he must also be a medic or an engineer — i.e., he is capable of fighting with few resources and making inventive use out of those resources which he does have at hand. For Taietti, this means that each piccolo attore will have to “train” its members to diffuse the group’s messages with clarity and efficiency. Of equal or even greater importance is that the members must also learn to attack, bombarding their adversaries’ posts on social media with criticism. This is a fundamentally serious way of living politics. In the Anglosphere, especially online, it often seems as if all the “content” is merely entertainment. There is no distinction between consumatore, simpatizzante, and militante. Scattered individuals follow accounts for no particular reason beyond liking their “content.” The Anglosphere could do with getting a bit more serious and forming the ethos of a militante. We don’t do what we do for fun or amusement, and if that is all someone wants or expects, then that person is not actually a part of the movement. That person is a consumatore, and should be treated as such.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Year America Died here.

How to create militanti? Taietti’s years of working with CasaPound provide the best advice. A small political operation must rely not only on social media. There needs to be a real-life setting: a headquarters, and face-to-face interaction. A radical Right organization which builds a headquarters should take care that it is more than just a drab office space with some computers and printers. It should be a library, a coffee shop, and — something that is increasingly in importance and popularity — a gym. This is where bonds of fellowship are tightened, and where ideas are clarified and communication skills honed. In continental Europe, locales such as these are common enough.

It also helps to operate within a parliamentary political system which allows for the formation and existence of many parties, and where a small party can fight in elections and, while not achieving anywhere near a majority of the votes, can still win enough votes or seats to have a say, or at least influence things a bit. In places such as the United States and the United Kingdom, countries that have come to be dominated by only two parties that are more or less the same on most important issues, the creation of these types of locales serves more of a social purpose. But even in ossified uniparty nation-states, the strategies of political witchcraft can still be effective.

Taietti is quick to inform us, however, that the role of the militante has to be updated for today, and nowadays it is the simpatizzante who is at times more vital for the success of a small political player. Old-fashioned parties had a need for ideologically-motivated activists. Political parties of the 1990s such as Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia had almost no need for activists because, with their idealism and ideology, they would only have gotten in the way of the party leaders and their ambitions. The political party of the twenty-first century needs something different. Taietti calls it the “network party.” In this setup, all four categories — consumer, supporter, activist, and leader — are tethered together in a network of internal rapport. The party leader communicates directly through social media and then, because of said rapport, the leader’s message is spread through the activists to the casual supporter, and finally to the eyes and ears of the normie voter. In this way, the message is also modified and adapted for whatever the target audience might be. Taietti cites the rise of Matteo Salvini as an example of how this works in practice. The advantages are obvious: control of the message, elimination of the need for mainstream media exposure, and low costs.

Fishing for Voters

Guido Taietti puts forth another concept of significant value: Fishing for voters and supporters who already exist rather than trying to convince people to become voters or supporters. This is particularly useful advice for those who consider themselves radicals and dissidents. It means reorienting the aim of their message. There are countless disillusioned voters out there, ready and waiting to form a solid base for alternative parties. Perhaps there are even disillusioned “Leftists,” well-to-do liberals who live in what used to be pleasant neighborhoods that have grown decrepit and dangerous thanks to certain immigration policies (for example). It’s not so much a question of adding to one’s own numbers as much as it is a question of taking away from the numbers of the other parties. This is why good optics and having a message that can be adapted to specific targets is essential.

Creating Problems, Not Trying to Solve Them

In the first chapters of Stregoneria Politica, Taietti briefly describes the utility in creating problems rather than solving them. This is one of his most interesting ideas for dissidents. We often obsess over insurmountable obstacles and grow ever more demoralized because of problems which seem to have no solution. With a shift of thinking towards the radical and revolutionary, the dissident can realize that his job isn’t to solve the problems created by the establishment. His job is to cause problems for the establishment.

Taietti cites the feminist movements in the United States and northern Europe as examples. Feminists aren’t very interested in solving any of the so-called problems they identify. In fact, in places such as the United States, where feminism has been around for quite a while, women’s overall satisfaction with life has actually decreased. Feminism hasn’t been transformed into a winning political force. Political parties don’t run on an explicitly feminist ticket, even if they mouth many of their talking points. Feminism’s power rather resides in its cultural influence, in its constant seeking out of new patriarchal dragons to slay. Feminism isn’t concerned with improving the lives of women as much as it is concerned with mobilizing women at opportune moments in order to obtain more cultural domination and visibility.

A perfect example of this recently played out in Spain. After the Spanish women’s football team won the World Cup, the President of Spain’s football governing body was embraced by one of the players, and in a moment of euphoria, they shared a peck on the lips. No one, not even the player, thought much about it. In fact, most media outlets reported on the kiss in between laughs and smiles. But Spain’s feminists sensed blood in the water. Within a matter of days, they managed to reshape reality and transformed what was merely an “anecdote,” to quote the female soccer player who was involved, into an international scandal. The player changed her story from one of a light-hearted moment in which she consented to a quick kiss, to one of sexual assault. The spotlight was also taken away from the players who had actually won a victory on the pitch. The joy of victory was replaced with bitterness, recrimination, hate, and blackmail. In the end, the feminists seized the opportunity to create a problem where there was none in order to use their freshly-obtained visibility to raise hell about the supposed “wage gap” between male and female footballers . Socially and culturally, Spain’s feminist movements achieved another “win” by doing what they always do: nag and complain. Yet, in the political arena they achieved nothing. In the recent national elections, the Leftist-feminist political party Sumar got the worst results out of the main four contenders (Partido Popular, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, Vox, and Sumar). No one votes for the feminists, yet they have immense power because they don’t bother trying to solve problems; they create them and then use them for their own ends.

You can buy The Alternative Right, ed. Greg Johnson, here

Dissidents can learn a lot from this. Consider the recent viral campaign on X to ban the Anti-Defamation League. The call to ban this hypocritical and mendacious organization arose thanks to a few X users who pointed out various nefarious deeds in the ADL’s past. Soon it turned into a hashtag that appeared in nearly 300,000 posts within a matter of 24 hours. Elon Musk began responding to several of the posts which brandished the hashtag, decrying the mafia-like behavior that the ADL has been engaging in to undermine his app’s earnings potential. As of this writing, there is a rumor that Musk is going to sue the ADL for — irony of all ironies — defamation.

Yet, as often occurs, several voices on the dissident Right began wrapping a wet blanket around the movement to bring justice to the ADL. “What is it going to accomplish? It’s taking attention away from other issues. Complaining about false accusations of anti-Semitism still gives legitimacy to the idea that anti-Semitism is some sort of crime. Musk can’t be trusted. The lawsuit cannot succeed.” Etcetera, etcetera. This is the “solve problems” mode of thinking. Perhaps instead the dissident Right should sit back and be content with forcing both Elon Musk — who is indeed not on our side, nor is he someone to put much trust in — and the ADL to come to a reckoning. Let the richest man in the world and a powerful Jewish interests group duke it out. Millions of people are now learning of the ADL’s evils. The dissident Right has created, or at least helped create, a problem for both the higher-ups at X as well as at the ADL. It’s not our problem to solve. All we have to do is take advantage of the problem itself.

A Thought-Provoking Perspective

The rest of Taietti’s book delves into matters such as the strategic use of “misinformation” and trolling. It’s akin to Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals, but updated for the age of mass media and the Internet of Things — and directed at those on the Right. Some of the themes will be very familiar to dissident readers: the rise and fall of the Alt Right, Steve Bannon’s strategy during the 2016 US presidential election campaign, and so on. In this author’s opinion, the best parts of the book come from Taietti’s Italian perspective. As mentioned earlier, there is a long-standing tradition of genuine Right-wing thought and activism in the Bel Paese that the Anglophone Right can learn from.

One comes away from Taietti’s manual with the realization there are, in fact, political solutions. There may be fewer, or no, electoral solutions — and that may be only temporary. But Taietti stresses that doing politics goes far beyond the elections held every two to five years. For those of us who are serious about what we do and why we do it, elections are perhaps the least important thing. The radical revolutionary mindset is to change the culture and change systems, and Taietti believes that there are ways of accomplishing it.

Italian speakers can already read for themselves what those ways are by getting their hands on Taietti’s book wherever it is sold — and happily, Stregoneria Politica will be translated into English soon.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate at least $10/month or $120/year.

- Donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Everyone else will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days. Naturally, we do not grant permission to other websites to repost paywall content before 30 days have passed.

- Paywall member comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Paywall members have the option of editing their comments.

- Paywall members get an Badge badge on their comments.

- Paywall members can “like” comments.

- Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, please visit our redesigned Paywall page.