Post-War Political Violence in Japan: A Harbinger of Things to Come?

The creation of the Japan Self-Defense Forces in 1954 was an indication of the country’s sharp turn away from demilitarization as the US sought to turn Japan into a Cold War ally.

1,898 words

I will be writing this story mostly as an ignorant Occidental. I freely admit there are important nuances of the following events and characters which remain beyond my grasp. After all, the majority of the source material is in Japanese. Regardless, I found this story so riveting, and the pause it gave me so contemplative, that I feel the need to share it.

After Japan’s surrender in the Second World War and Emperor Hirohito’s subsequent renunciation of his divine status, the Japanese were a people without a clear national identity. This may be what you would expect from any defeated nation, but the 180-degree cultural turn General Douglas MacArthur demanded of the Japanese during the seven-year American occupation of Japan was quite daunting. After decades of rapid modernization and militaristic hyper-nationalism, the Japanese in the early 1950s found themselves without a true military, without leaders of industry, without centralized police, and with liberal Enlightenment values being forced upon them. In particular, women were enfranchised, the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and other Leftist political entities were sanctioned, and workers were given the right to organize and strike.

After the rise of Mao Zedong in China in 1949 and the increasing chill of the incipient Cold War being felt in Washington, the Americans began to see Japan more as a junior partner in their greater geopolitical struggles than as a dangerous former enemy which needed to remain disarmed. As a result, MacArthur cracked down on those labor unions which opposed Japan’s pro-American Prime Minister and remilitarized Japan so that it could support American interests in the Cold War’s Asian theater. Thousands of purged wartime Japanese leaders and officers were allowed back into public life, and Japan once again had a centralized national police force and powerful industrial conglomerates. Whereas nationalists and other Rightist figures had been purged immediately following the war, by 1950 thousands of Communists were being removed from both the government and the private sector.

This “reverse course” cleared the way for a colossal struggle in Japan between Right and Left which would consume much of the 1950s and culminate in June 1960 during the historic conflict over revising the one-sided and humiliating US-Japan Security Treaty of 1952. This revision became known by its abbreviation “Anpo” in Japanese. Essentially, both political beasts had been let loose from their respective cages, and for the first time in Japanese history they went at each other in government, and ultimately in the streets. Instead of bowing to American pressure, the Japanese labor unions and other Leftist organizations bounced back with greater strength and energy. In 1954, the National Police Reserve became the Japan Self-Defense Forces, and soon after the two largest Right-wing parties merged into the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) — an inapt English moniker if there ever was one — in which future Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke played an important role. A similar convergence occurred on the Left with the formation of the Japan Socialist Party (JSP), which was led in 1960 by Asanuma Inejirō. The CIA aided the LDP, while Leftist organizations looked to Communist China for support.

This all came to a head in 1960 when Prime Minister Kishi had, through some political chicanery, ratified the Anpo treaty. Despite the fact that this revision greatly improved Japan’s stature vis-à-vis the United States, it came hard on the heels of Kishi’s ill-advised attempts to sharply increase national police power. Thus, in the eyes of the Left opposing the treaty revision was more about opposing Kishi than the treaty itself. After ratification — and four days before President Eisenhower was scheduled to arrive in Japan — the Left’s reaction was swift and furious. Here is how Nick Kapur describes the tumult in his 2018 book, Japan at the Crossroads:

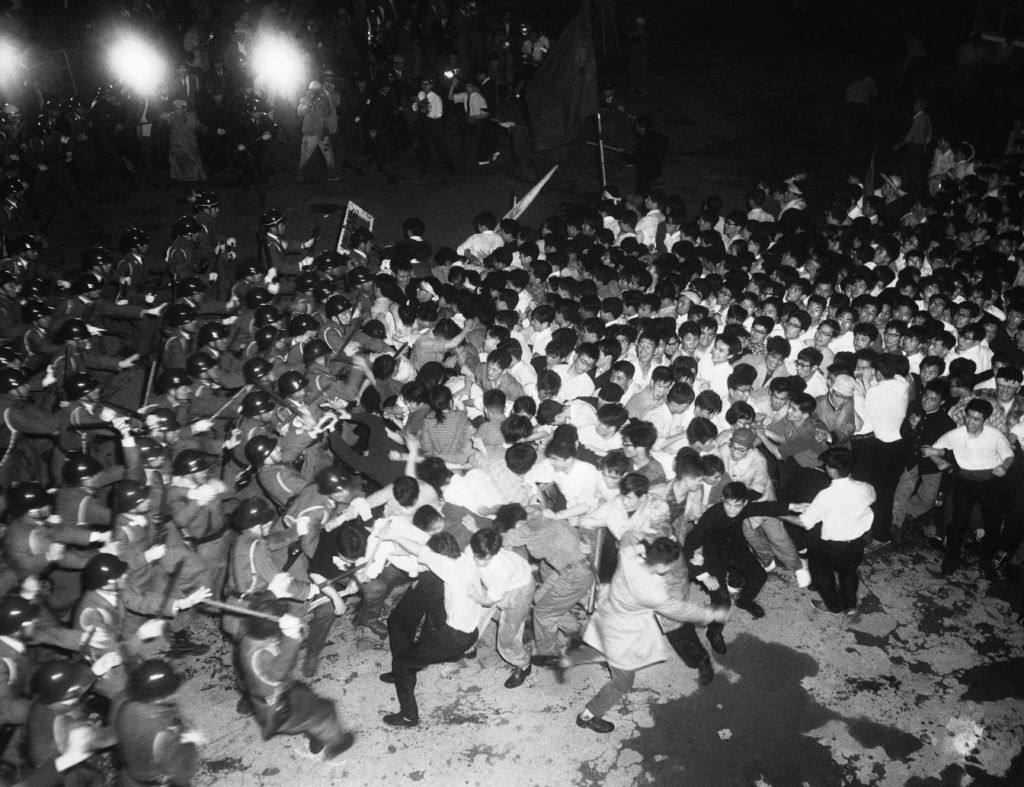

An astounding scene greeted Japanese people turning on their radios and newly purchased television sets on the evening of June 15, 1960. As they watched or listened live in their living rooms, thousands of protesters, many of them students from Japan’s most elite universities, smashed down the gates of the symbol of Japanese democracy itself — the National Diet Building in central Tokyo. Amid the harsh, eerie lighting of burning police vehicles and klieg lights brought in by television film crews, wave after wave of unarmed protesters crashed against ranks of helmeted police officers armed with truncheons, attempting to force their way into the building housing Japan’s national legislature through the sheer force of their massed bodies. The desperate battle raged long into the night and ultimately left hundreds bloodied and battered, and a young female college student dead. It also threw Japan’s post–World War II political settlement, as well as Japan’s place in the Cold War international system, into a state of profound uncertainty.

You can buy Spencer J. Quinn’s young adult novel The No College Club here.

Imagine being a nationalist — especially a Japanese ethnonationalist — and watching this chaos unfold. With pre-surrender memories still vivid in the minds of many, it could have seemed as if the future of Japan itself was on the line in June 1960, almost as much as it had been in August 1945. Yes, Right-wing counter-protestors were making their presence felt. But would Japan become a Communist state regardless? Would the atrocities that had occurred in the Soviet Union and China also happen in Japan? And thinking beyond Japan, would its capitulation to the Left ultimately shift the balance of the Cold War in Asia in favor of the murderous and expansive Communists?

Some of these nationalists may have supported a close, mutually beneficial alliance with the United States. Some may have advocated a neutral course that would have kept Japan out of Cold War politics as much as possible. And others still may have simply opposed the US presence in Japan and its ongoing nuclear testing in the Pacific (which, incidentally, provided the inspiration for the first Godzilla movie in 1954). In any case, something had to be done to quell the Japanese Left’s sudden and ruthless rise. In response came the resurgence of a serious and militant Japanese Right.

According to Kapur:

The darkest side of the renewed right-wing confidence in 1960, however, was a wave of spectacular assassinations and assassination attempts that evoked memories of a similar wave of assassinations that had wracked Japan in the 1930s. Socialist Party leader Kawakami Jōtarō was stabbed by a right-wing youth on June 17, 1960, as was Kishi himself on July 15 (although both eventually recovered). Most spectacular of all was the fatal stabbing of Socialist Party chairman Asanuma Inejirō during an election debate on October 12, witnessed live on national television by a stunned audience of millions.

The assassin was 17-year-old Yamaguchi Otoya. Having grown up fairly well off as the son of a Self-Defense Forces officer, the mentally unstable Yamaguchi had been radicalized by his older brother and joined the nationalist Greater Japan Patriotic Party at 16.

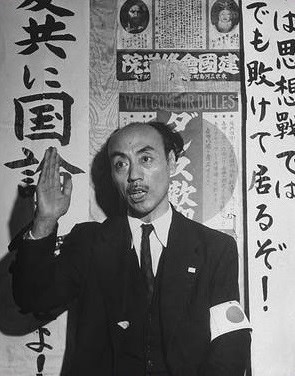

The party’s leader, Akao Bin, had proclaimed himself “Japan’s Hitler,” and consistently preached that Japan was on the verge of a Communist revolution. Unfortunately for Yamaguchi, Akao was not radical enough for him. Yamaguchi felt that Akao was all talk and not enough action, and so resigned from the party in May 1960.

Five months later, Yamaguchi assassinated the bull-necked Asanuma Inejirō in the middle of a televised debate by running him through with a samurai sword. Yamaguchi was apprehended before he could commit suicide. It was all captured live and horrified millions. The strikingly clear photograph of the assassination taken by Yasushi Nagao won the World Press Photo of the Year in 1960 and a Pulitzer in 1961.

After his arrest, Yamaguchi complied perfectly with the authorities, freely offering his testimony and motives. On November 2, while in prison, he mixed toothpaste with water and wrote on his wall, “Would that I had seven lives to give for my country. Long live the Emperor!” The phrase “seven lives for my country” refers to the last words of a famous fourteenth-century samurai. After writing this note, Yamaguchi hanged himself with knotted bedsheets.

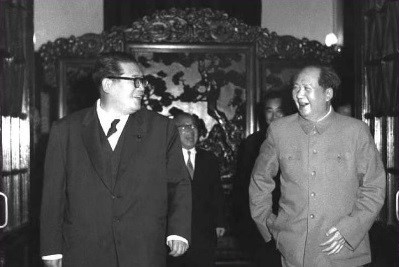

As for Asanuma Inejirō, he had started out in politics in the 1930s as a nationalist and a hawk who supported Hideki Tojo’s military regime. After the war, he reentered politics as a socialist and supported the Chinese Communist Party. From 1955 to 1960, he served as Chief Secretary and later as Chairman of the JSP. The year before his death he had visited the People’s Republic of China, during which time he cozied up to Mao in Beijing and declared that the United States was the mutual enemy of both China and Japan. This happened when Japan, the United States, and many other countries had recognized the Republic of China — and not Mao’s China — as the only legitimate government of the Chinese people. Famously, Asanuma returned to Japan wearing a suit similar to the one typically worn by Mao, which sparked outrage among the Japanese.

It should be remembered that around this time, Mao’s Great Leap Forward was resulting in the starvation of tens of millions. Asanuma had become even more notorious by 1960 considering that his JSP had played a leading role in the riot at the Diet earlier that year.

So what to make of all this? Other than appreciating it as a fascinating slice of history, a combination of humility and ignorance is preventing me from coming to any solid conclusions. From a Western perspective, however, I do find it interesting that even in an ethnically homogeneous nation such as Japan, violent and lethal political strife is still possible. Many on the dissident Right in America will look at the Summer of Floyd and blame it — at least in part — on racial diversity. Diversity + Proximity = War, as the mantra goes. Then how to explain political violence that took place in Japan in 1960?

This is something I believe that the Japanese today might need to ponder, given the fact that there has lately been increased international pressure for them to allow more immigration into their country. We in the West know very well how poorly that can turn out, and one can only hope that Japan’s leaders know this as well. If Japan is to survive, and not ultimately degenerate into a mongrel plaything of the Left, its citizenship must continue to be tied to blood.

Perhaps as terrible as they were, the events of 1960 would have occurred more often and been greater in scale had there been sizable ethnic or racial minorities living in Japanese cities — minorities that the Left could have riled up and used as weapons, as it does in the West. Perhaps with only Japanese living in Japan, there was an overarching balance between Left and Right — despite occasional flare-ups as in 1960. And perhaps with sizeable foreign emigration, this balance might one day be in jeopardy.

These presumptions do jibe with the way in which the multiracial West has been far more volatile than Japan since the Second World War. The widespread Nahel Merzouk riots in France are an excellent recent example. Do the Japanese want to endure that kind of trauma? If they continue to allow non-Japanese immigration, I’m afraid they will. And then the bad old days of 1960 might seem good in comparison.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “Paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

- Third, Paywall members have the ability to edit their comments.

- Fourth, Paywall members can “commission” a yearly article from Counter-Currents. Just send a question that you’d like to have discussed to [email protected]. (Obviously, the topics must be suitable to Counter-Currents and its broader project, as well as the interests and expertise of our writers.)

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here:

Paywall Gift Subscriptions

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

If you are already behind the paywall and want to share the benefits, Counter-Currents also offers paywall gift subscriptions. We need just five things from you:

- your payment

- the recipient’s name

- the recipient’s email address

- your name

- your email address

To register, just fill out this form and we will walk you through the payment and registration process. There are a number of different payment options.