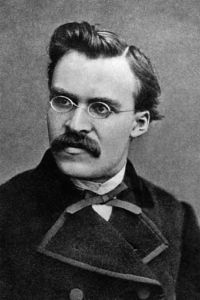

Nietzsche and the Psychology of the Left, Part Two

Part 2 of 2 (Part 1 here)

4. The Ascetic Ideal

The third essay that makes up On the Genealogy of Morality is concerned with asceticism, as it has exhibited itself in religion and in philosophy. Nietzsche writes:

I can think of hardly anything that has sapped the health and racial strength of precisely the Europeans so destructively as [the ascetic ideal]; without any exaggeration we are entitled to call it the real catastrophe in the history of the health of Europeans.[1]

His analysis of asceticism is a direct application of the ideas we discussed in Part One, for he understands it to be a manifestation of slave morality. Indeed, some of Nietzsche’s most famous statements about slave morality are actually made in the context of discussing the ascetic ideal. What Nietzsche says about asceticism can thus help us to understand slave morality more fully.

Nietzsche states that within the soul of the ascetic “an unparalleled ressentiment rules,” and he characterizes the ascetic as a “contradictory type” whose life is “self-contradiction.” Why? Because here “an attempt is made to use power to block the sources of power.” By the “sources of power,” Nietzsche essentially means life itself. The ascetic is someone who advances himself and his own status and power by setting himself against the conditions that make healthy, flourishing human life possible. The ascetic turns “the green eye of spite” onto “physiological growth itself, in particular the manifestation of this in beauty and joy; while satisfaction is looked for and found in failure, decay, pain, misfortune, ugliness, voluntary deprivation, destruction of selfhood, self-flagellation and self-sacrifice.”[2]

The conflict or contradiction within the ascetic “wills itself to be conflicting.” In other words, the ascetic is a living human being who wills the negation of his own life — yet remains alive. It is this negation, in fact, for which he lives. He “relishes” this morbid state and “becomes more self-assured and triumphant to the same degree as [his] own condition, the physiological capacity to live, decreases.”[3] If the ascetic begins to philosophize, he will turn his nihilating dialectic against everything that healthy human beings regard as “true and real.” He will look for error “precisely where the actual instinct of life most unconditionally judges there to be truth.”[4]

Thus, the ascetic will attack everything that our most basic and healthy instincts tell us is true, and conducive to a good human life. For example, the ascetic may even declare that the physical world itself is an illusion (Nietzsche offers the “ascetics of the Vedanta philosophy” as an instance of this). The ascetic will “deny his ego” or even his own existence. Nietzsche describes the “voluptuousness” of asceticism as reaching its peak when it declares that there is “a true world” beyond this realm of illusion, but that “reason is firmly excluded from it.”[5] In other words, there is a true world, but the human intellect is impotent to know it. It is accessible, however, through the feelings and mystical instincts of . . . guess who? Why, the ascetic, of course.

It can easily be seen that in asceticism ressentiment reaches its zenith. Faced with a world in which their weakness makes them unsuited to live, the ascetics — a kind of advanced slave or priestly type — have expressed their hatred by annihilating life and, indeed, all of existence — but only in thought. Effectively, Nietzsche is attacking the entire history of metaphysics from Parmenides to the German idealists — as well as all religion, East and West, and all mysticism. He warns us to beware of conceptions of “a pure, will-less, painless, timeless, subject of knowledge,” as well as such notions as “pure reason,” “absolute spirituality,” and “knowledge as such.”[6] His main targets here are Descartes, Kant, Fichte, and Hegel — and of course, Socrates and Plato.

Nietzsche takes aim at Socrates throughout his writings. For example, he devotes an entire chapter to Socrates in Twilight of the Idols (published two years after Genealogy, and intended as an introduction to Nietzsche’s thought). There he writes that “The wisest sages of all times have reached the same judgment about life: it’s worthless.” These sages exhibit “hostility to life,” Nietzsche tells us. He reminds us that Socrates belonged to “the lowest folk”; indeed, that he was “rabble” (Pöbel). He was also quite ugly, and don’t “forensic anthropologists tell us that the typical criminal is ugly”?[7] (Here again we see the importance Nietzsche places on physiology.) He thus raises the possibility that Socrates’s famous irony is an expression “of the rabble’s ressentiment,” and that Socratic dialectic may be “just a form of revenge.”[8]

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The Trial of Socrates here.

The “asceticism” of Socrates, elaborated by Plato, consists in denying this world in favor of a transcendent realm of ideals to which, conveniently, only the physiologically unprepossessing philosophers have access (for a similar physiological assessment of the philosophers, see Aristophanes’s Clouds). Analogously, in the realm of religion, the priests tell their flock that only they can intercede for them with heaven, and thus only by obedience to priests can souls be saved from eternal damnation. Nietzsche mentions the famous lines in Phaedo where Socrates speaks of life as an affliction and, as he lays dying, declares that he “owes a rooster to Asclepius” (it was customary for those who had been healed of an illness to sacrifice a rooster to Asclepius, the god of medicine). To say the least, by the way, Nietzsche’s reading of Socrates-Plato is highly tendentious — though we cannot explore the case against it here.

Nietzsche at one point characterizes asceticism — “this hatred of the human, and even more of the animalistic, . . . this fear of happiness and beauty” — as, at root, a “will to nothingness.” Nevertheless, Nietzsche says that this will to nothingness “is and remains a will.”[9] In other words, in Socrates’ or the priest’s negation of life, there is still present the sort of striving that is characteristic of life itself. As everyone knows, Nietzsche taught that life is will to power. And the ascetic ideal is one manifestation of will to power — hence, one form in which the life force expresses itself. In spite of appearances, therefore, the ascetic ideal is a “life strategy” aiming not just at survival but at personal aggrandizement — one which is founded, paradoxically, upon seeming to renounce and undermine life.

Nietzsche writes that

the ascetic ideal springs from the protective and healing instincts of a degenerating life, which uses every means to maintain itself and struggles for its existence; it indicates a partial physiological inhibition and exhaustion against which the deepest instincts of life, which have remained intact, continually struggle with new methods and inventions. The ascetic ideal is one such method: the situation is therefore the precise opposite of what the worshippers of this ideal imagine, — in it and through it, life struggles with death and against death, the ascetic ideal is a trick for the preservation of life.[10]

Living things cannot choose death in the sense of mere negation or nullity. All actions are willed, and all willing seeks power. Even the choice to commit suicide is the choice of what one tacitly thinks will be an improvement over one’s present state (“I’d be better off dead,” the despondent sometimes say, when in fact death means the absolute end of the I and its betterment). Life is always seeking its own good, though this often takes perverse forms; forms that may seem obviously self-defeating to others (suicide being just a particularly clear example). As Nietzsche puts it, a basic fact about human will is its “horror vacui; it needs an aim — , and it prefers to will nothingness rather than not will.”[11] This point is so important for him that he repeats it at the very end of the book.[12]

For us, in our own historical situation, the takeaway is simply what we have suspected for some time: that there is a method in the madness of those in our midst who are seemingly out to destroy everything that is conducive to healthy human flourishing (hierarchy, heterosexuality and the family, masculinity and femininity, reason, any and all standards, and now even physical fitness), while simultaneously championing everything that undermines it or reeks of its absence (weakness, fatness, victimhood, deviant sexuality, “diversity,” “equity,” etc.). It is a strategy by which resentful misfits seek status, influence, and power.

5. The Jews

So far we have said nothing at all about the Jews, to whom Nietzsche refers as “a priestly nation of ressentiment par excellence, possessing an unparalleled genius for popular morality.”[13] Indeed, I had forgotten just how vitriolic the treatment of the Jews is in On the Genealogy of Morality. This topic has been debated for about a century, with many Nietzsche scholars working hard to acquit him of the charge of anti-Semitism. This is a peculiar thing about the academic treatment of Nietzsche: you would think that any philosopher who was this anti-egalitarian, this anti-democratic, this scornful of the weak in body and spirit, this determined to explain Leftism as moved by ressentiment, and this anti-Semitic would have been expunged from the canon years ago. But many Nietzsche scholars actively whitewash his heresies. To be sure, Nietzsche is no racialist: He does not proclaim the superiority of any one race, nor, given the scorn he pours on modern Germans, could anyone mistake him for a nationalist.

Nietzsche writes that “the slaves’ revolt in morality begins with the Jews: a revolt which has two thousand years of history behind it and has only been lost sight of because — it was victorious.”[14] And, further:

Nothing that has been done on earth against “the noble,” “the mighty,” “the masters” and “the rulers,” is worth mentioning compared with what the Jews have done against them: the Jews, those priestly people, which in the last resort was able to gain satisfaction from its enemies and conquerors only through a radical revaluation of their values, that is, through an act of the most deliberate revenge.

Nietzsche implies that the “inversion of values” we spoke of in the last installment was first effected by the Jews. In other words, they were the first to reject what Nietzsche calls the “aristocratic value equation” (“good = noble = powerful = beautiful = happy = blessed”) and to create a new table of values that was the inversion of those of the aristocrats (“the masters”).[15] Nietzsche sums up these new, Jewish values as follows:

Only those who suffer are good, only the poor, the powerless, the lowly are good; the suffering, the deprived, the sick, the ugly, are the only pious people, the only ones saved, salvation is for them alone, — whereas you, the noble and powerful, are eternally wicked, cruel, lustful, insatiate, godless, will also be eternally wretched, cursed and damned![16]

In Moses the Egyptian, German Egyptologist Jan Assmann puts forward a theory of what he calls “normative inversion” to explain how Jewish values and religious precepts came about. “Normative inversion” involves exactly what it sounds like: arriving at new norms through “inverting” the norms of a hated tradition or people. Greg Johnson summarizes Assmann’s conclusions as follows:

[The] Jews arrived at their concept of the sacred simply by inverting and profaning what the Egyptians regarded as sacred. For instance, since the Egyptians held the bull and the ram to be sacred animals, Jewish law prescribes that they be sacrificed. Although Assmann does not draw this conclusion, his argument supports the idea that the “slave revolt in morals” that Nietzsche saw at the root of Christian morality goes all the way back to the creation of Judaism at Mount Sinai. Judaism, in short, is no more a religion than Anton LaVey’s Satanism is. Both are just counter-religions, i.e., hateful inversions — “Satanic” parodies — of other religions or counter-religions.

Certainly, Assmann’s “normative inversion” is, for all intents and purposes, indistinguishable from what Nietzsche refers to as the Jews’ “radical revaluation of values.” Johnson also helpfully points out that “The Babylonian Talmud (Sabbat 89a) claims that Sinai received its name because it is the place from which hate (sin’ah) descended upon the world” (though the Talmud claims, unsurprisingly, that “the hate comes from the goyim who are jealous of the chosen”).

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Summoning the Gods here.

Certainly, the Jews were already seen in the ancient world as a people motivated by hatred. Nietzsche says that the Romans saw the Jew as “something contrary to nature.” He cites Tacitus (Annals XV. 44) as saying that the Jews were “convicted of hatred against the whole human species.”[17] In his Histories (V.5), Tacitus claims that the Jews “are obstinately loyal to each other, and always ready to show compassion, whereas they feel nothing but hatred and enmity for the rest of the world.”

Even when Nietzsche does not explicitly reference the Jews, he clearly seems to have them in mind, as when he contrasts the noble man with the “man of ressentiment.” While the noble man is upright, honest, and even something of an innocent, the soul of the man of ressentiment “squints.” His mind “loves dark corners, secret paths, and back-doors.” Further, “he knows all about keeping quiet, not forgetting, waiting, temporarily humbling and abasing himself.”[18] I would contend that Nietzsche simply had to have had the Jews in mind when he goes on to say that “A race of such men of ressentiment will inevitably end up cleverer than any noble race, and will respect cleverness to a quite different degree as well.”[19]

Since Christianity began as a Jewish heresy, Nietzsche inevitably sees it as the product, in effect, of a Jewish conspiracy. Christianity is usually presented to us as offering an ideal of “universal love” that, among other things, constitutes a repudiation of the hatred Jews have historically exhibited toward all nations other than themselves. Nietzsche, however, tells us that just the opposite is true:

This love grew out of the hatred, as its crown, as the triumphant crown expanding ever wider in the purest brightness and radiance of the sun, the crown which, as it were, in the realm of light and height, was pursuing the aims of that hatred, victory, spoils, seduction with the same urgency with which the roots of that hatred were burrowing ever more thoroughly and greedily into everything that was deep and evil.[20]

Jesus of Nazareth, Nietzsche tells us, was a sinister seducer whose teachings constitute a “circuitous route” back to Jewish values born of hate. With Christianity, the Jews reached the pinnacle of their “sublime vengefulness” via this “redeemer” who was, after all, only an “apparent opponent” of Israel.[21] Indeed, for Nietzsche the Jewish invention of Christianity is “part of a secret black art of a truly grand politics of revenge, a farsighted, subterranean revenge, slow to grip and calculating . . .”[22]

According to Nietzsche, the Jews were so diabolical they realized that to throw people off the scent it would be necessary to “denounce [their] actual instrument of revenge [i.e., Christ and his teaching] before all the world as a mortal enemy . . .” Thus was Christ handed over to the Romans and nailed to the cross, with all Israel’s enemies hoodwinked thereby into thinking that Christ had been repudiated by his own people. Israel’s enemies thus could “safely nibble at the bait”: the enticing, intoxicating power of “God on the Cross,” sacrificing himself for the salvation of man. Israel, “with its revenge and revaluation of former values,” thus triumphed.

At least it did so in the West, where the dysgenic, deracinating poison of Christianity enfeebled the souls of noble men and made them virtually powerless to resist the machinations of the Jews. Nietzsche writes:

You might take this victory for blood-poisoning (it did mix the races up!) — I do not deny it; but undoubtedly this intoxication has succeeded. The salvation of the human race (I mean, from “the Masters”) is well on course; everything is being made appreciably Jewish, Christian or plebeian (never mind the words!). The passage of this poison through the whole body of humankind seems unstoppable . . .[23]

Nietzsche reminds us that Dante included an inscription over his entrance to Hell: “Eternal love created me as well.” Nietzsche dismisses this as an expression of “awe-inspiring naivety,” and suggests instead that the following inscription ought to hang over the gateway to the Christian Paradise, as a summation of Christianity’s real raison d’être: “Eternal hate created me as well.”[24]

6, Conclusion: Nietzsche for the Twenty-First Century

Is Nietzsche fair to the Jews and to Christianity? Earlier I declined to go into detail about whether he is fair to Socrates and Plato (I think, in fact, that he is not). You see, in this essay my objective is merely to present Nietzsche’s ideas — insofar as they are helpful for understanding the motivations of the Left — and not to critique them. But I will note here, just briefly, that I think that ressentiment has certainly always been a salient feature of Jewish psychology. As we saw earlier, this was noticed even by the ancients. Is it the motivating factor for everything Jews do? Certainly not.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s From Plato to Postmodernism here

Is Christianity a religion of slave morality? Ressentiment certainly may have been a factor in the motives of the first Christians, and some Christians who’ve lived since. But through the centuries there have also been many devout Christians in whom one finds no trace of this. Was Christianity invented by the Jews as a device to undermine other people’s cultures, thus making it easier for Jews to exploit them? The idea that Christianity was the result of a conscious plot seems implausible to me (and Nietzsche may not, in fact, believe that — even though he seems to write as if he does).

Nevertheless, it is quite true that Christianity is a fundamentally dysgenic belief system, given its egalitarianism and its rejection of “love of one’s own” in favor of an impossible ideal of “universal love.” It does function to weaken ethnic solidarity, and it therefore does ultimately serve Jewish interests. Probably the most reasonable approach here is the one taken by Kevin MacDonald, who recognizes that the Jews do not have to consciously and deliberately “plot” anything. They are just so fiercely ethnocentric that whatever they contribute to the culture — Marxism, psychoanalysis, Boasian anthropology, critical theory, multiculturalism, Hollywood, etc. — winds up advancing Jewish interests nonetheless. There is certainly plenty of justification for seeing Christianity as another such “Jewish movement.”

Whatever may be the limitations of Nietzsche’s ideas in On the Genealogy of Morality, I think that all the foregoing should have convinced the reader that he has provided us with some powerful tools for understanding today’s looney Left. We are appalled by the ideas of the Left, but we are also appalled (and, if truth be told, fascinated and amused) by the people who have emerged in the last couple of decades as their mouthpieces: those shapeless, androgynous, highly neurotic misfits, often with unnaturally colored hair: the Soy Boys, the SJWs, the simps, the transgendered, etc. It’s one thing to be faced with an enemy you hate — one that has managed to acquire considerable influence. But it’s quite another matter, and a disconcerting one, to face a powerful enemy that is simultaneously laughable and pathetic. I was reminded of this when I read the following from Nietzsche:

We may be quite justified in retaining our fear of the blond beast at the center of every noble race and remain on our guard: but who would not, a hundred times over, prefer to fear if he can admire at the same time, rather than not fear, but thereby permanently retain the disgusting spectacle of the failed, the stunted, the wasted away and the poisoned? And is that not our fate? What constitutes our aversion to “human beings” today? — For we suffer from man no doubt about that. — Not fear; rather, the fact that we have nothing to fear from man; that “man” is first and foremost a teeming mass of worms; that the “tame man,” who is incurably mediocre and unedifying, has already learned to view himself as the aim and pinnacle, the meaning of history, the “higher man.”[25]

It may be amusing to make fun of our current crop of freaks, but Nietzsche would advise us that this is actually serious business, and that our visceral revulsion at these folks is an important guide to truth. He would advise us, in short, to take physiology seriously. I recently read two books by the evolutionary psychologist Edward Dutton: Breeding the Human Herd and Spiteful Mutants, and was delighted to find much that constituted a scientific elaboration of Nietzsche’s ideas about physiology.

Dutton theorizes that looney Leftism is largely the result of a lack of genetic fitness. Leftists are, in his delightful phrase, “spiteful mutants” with “high mutational load” that results in an unusually large number of physical and mental abnormalities (as well as, very often, an unattractive appearance; physical attractiveness being highly correlated with low mutational load). In the pre-industrial West, these individuals would probably never have reached adulthood, but technological and medical advances have prevented natural selection from operating as it normally would. Dutton supports his claims by appealing to recent research in the social sciences — for example, studies that show a high correlation between espousing Left-wing views and a number of heritable psychopathologies.

Not only does being Left-wing correlate with low agreeableness, low conscientiousness, and high neuroticism, being far Left is also correlated with the so-called “dark triad” personality traits: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. The most readily detectable of these traits is narcissism — which we have all observed in virtue-signaling Leftists. They claim that they are concerned about equality and about fighting injustice, but psychological studies have cast doubt on this. Leftists do indeed identify with individuals or groups they regard as low in power. However, this appears to be due to the fact that they see themselves as weak and thus low in power as well. Similarly, they place so much importance on “equality” because they think they deserve more power than they have.

Given that Leftists see themselves as physically weak (and are usually right about this), they wind up seeking power in some kind of covert manner (remember: his mind “loves dark corners, secret paths, and back-doors”). Their strategy is to loudly and frequently virtue-signal about “social justice,” “equity,” and “diversity.” They positively adore self-abasement and are always ready to heap scorn upon their “whiteness” and “privilege.” The strategy is a clever one, because many people take them to be sincere idealists, and do not perceive that they are angling for status and power. “Victim signaling” is another such strategy and, according to recent studies, highly correlated with narcissism and Machiavellianism (the reader will have to turn to Dutton’s books for citations to these studies — of which he provides plenty). Dutton writes that the Leftist “loudly proclaims that he is compassionate and kind in order to hide the fact that he is selfish and ruthless and in order to allay his own feelings of inferiority by convincing himself and others of his moral superiority.”[26] One psychological study cited by Dutton identifies “malicious envy” as the single most significant motivator of radical Leftists.

The result is the bizarre spectacle we witness today of what Dutton calls an “ideological arms race” among Leftists, whereby they compete with one another to try and undermine every evolutionarily adaptive tradition or institution because they somehow or other promote injustice or inequality. In a new incarnation of the “ascetic ideal,” Leftists eventually wind up advocating their own destruction — whether by declaring that they will never reproduce, or by calling for the “abolition” of whiteness (and almost all of the looniest Leftists — and certainly the ones I’ve been discussing here — are white).

In short, dear reader, it’s ressentiment, slave morality, and the ascetic ideal all over again. The real danger of spiteful mutants (a.k.a. slave types) consists in their capacity to damage the healthy. Dutton warns us that “As mutational load rises, [relatively healthy people] will increasingly come into contact with mentally unhealthy people . . .”[27] How did slave morality triumph? By warping the minds of healthy people — by causing them to doubt their intuitions of their own fundamental goodness, and their right to happiness. It is the “priests” and the professors who have done this — to say nothing of the journalists, the entertainers, and the foot soldiers posting censorious comments on social media. Let us listen to Nietzsche one final time:

The sickly are the greatest danger to man: not the wicked, not the beasts of prey. Those who, from the start, are the unfortunate, the downtrodden, the broken — these are the ones, the weakest, who most undermine life among those who introduce the deadliest poison and skepticism into our trust in life, in human beings, in ourselves. . . . In such a soil of self-contempt, such a veritable swamp, every kind of weed and poisonous plant grows, all of them so small, hidden, dissembling and sugary. . . . These failures: what noble eloquence flows from their lips! How much sugared, slimy, humble humility swims in their eyes! What do they really want? At any rate, to represent justice, love, wisdom, superiority, that is the ambition of these who are the lowest, these sick people![28]

There is much else to be said about On the Genealogy of Morality, and about Nietzsche. But don’t rest content with getting your information from me. Go to the source. By the way, I part company with Nietzsche on the meaning of the word “evil.” I don’t see it as belonging exclusively to slave morality. The evil is what has set itself against life, and seeks to undermine — out of spite — health, happiness, strength, and normalcy. Make no mistake: evil is a reality, and our fight is a fight against evil. You will find that On the Genealogy of Morality can provide much inspiration and consolation in this ongoing struggle.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson, trans. Carol Diethe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 108. Unless otherwise noted, all italics in this and other quotations are Nietzsche’s own.

[2] Nietzsche, 87.

[3] Nietzsche, 87.

[4] Nietzsche, 88.

[5] Nietzsche, 88.

[6] Nietzsche, 88-89.

[7] Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, trans. Richard Polt (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1997), 13.

[8] Twilight, 15.

[9] Nietzsche, 133.

[10] Nietzsche, 89.

[11] Nietzsche, 69.

[12] Nietzsche, 123.

[13] Nietzsche, 33.

[14] Nietzsche, 18.

[15] Nietzsche, 17.

[16] Nietzsche, 18.

[17] Nietzsche, 33. Though Tacitus here references “those popularly called ‘Christians,’” Nietzsche apparently takes him to be referring to Jews.

[18] Nietzsche, 22. My italics.

[19] Nietzsche, 22.

[20] Nietzsche, 18

[21] Nietzsche, 18. My italics.

[22] Nietzsche, 18-19.

[23] Nietzsche, 19. First italics mine.

[24] Nietzsche, 30.

[25] Nietzsche, 25.

[26] Edward Dutton, Breeding the Human Herd: Eugenics, Dysgenics and the Future of the Species (Perth, Australia: Imperium Press, 2023), 132.

[27] Dutton, 142.

[28] Nietzsche, 91.