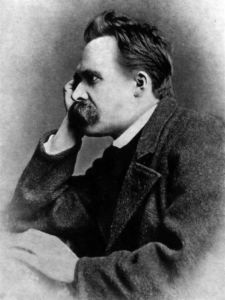

Nietzsche and the Psychology of the Left, Part One

1. Introduction: An Extremely Impious Book

Perplexed, as so many of us are, by the utter mindlessness and malevolence of today’s Leftists, I decided several years ago to undertake an ambitious project: developing a comprehensive theory of their psychology. I assembled an extensive reading list, including Dostoyevsky’s The Devils (which delighted me). When I reread Friedrich Nietzsche, however, I realized that I had almost nothing to add to what he had already said.

Many of my readers probably already know something about what Nietzsche called “slave morality” (Sklavenmoral) and its connection to the feeling of ressentiment (resentment).[1] And they are doubtless aware that Nietzsche uses these concepts to understand the Leftists of his own day, the origins of Christianity, and even the origins of Socratic-Platonic philosophy. The key text here is On the Genealogy of Morality (Zur Genealogie der Moral, 1887). On returning to it, I discovered that there was much here that I had forgotten — and that it was uncannily relevant to the present day, and our present crop of spiteful mutants.

The purpose of this essay is to introduce readers to some of the most important concepts in On the Genealogy of Morality. However, it is not intended to be a general introduction to the work. Nietzsche’s text actually consists of three essays, whose titles are as follows: (1) “‘Good and Evil,’ ‘Good and Bad’”; (2) “‘Guilt,’ ‘Bad Conscience,’ and Related Matters”; and (3) “What Do Ascetic Ideals Mean?” I intend to confine myself to the portions of the text most relevant to the understanding of Leftist psychology. Accordingly, I will focus primarily on the first and third essays (the concept of the “ascetic ideal” being a direct application of the ideas presented in essay one). I believe that the reader will agree with my assessment that Nietzsche’s ideas are virtually the last word in understanding what makes Leftists tick.

First, however, we need to understand Nietzsche’s title, The Genealogy of Morality. Early in the text, he writes that

we need a critique of moral values, the value of these values should itself, for once, be examined — and so we need to know about the conditions and circumstances under which the values grew up, developed and changed . . . since we have neither had this knowledge up till now nor even desired it.[2]

Hence, he will present a “genealogy” of modern, European values — i.e., a theory as to their origin and development. Nietzsche’s approach is truly revolutionary, for no one had thought to attempt this before. Instead, philosophers and others had taken a certain set of moral values “as given, as factual, as beyond all questioning.”[3]

Nietzsche intends to question the value of these values, in essence by arguing that they have arisen through ill will, and that they are inimical to life. No one before Nietzsche had dared raise such a possibility, for to do so would have been seen as extremely impious. Hence, the first thing to understand about On the Genealogy of Morality is that it is an extremely impious text. This — along with his claim that “God is dead” — is why Nietzsche has always been regarded as a dangerous figure. It is also worth pointing out that the subtitle of the book (usually omitted from most editions), is “A Polemic” (Eine Streitschrift).

Further, Nietzsche puts forward the radical idea that the origin of all values lies in “physiology.” Later in the text, he writes that “every table of values, every ‘thou shalt’ known to history or the study of ethnology, needs first and foremost a physiological elucidation and interpretation, rather than a psychological one; and all of them await critical study from medical science.”[4] Nietzsche means that the sort of values one chooses depends on what sort of man one is. Our understanding of the good will flow from the quality of our bodily being. A man with a robust and healthy physiology will choose one set of values; a man who is weak and sickly will choose quite another.

With this idea in mind, let us now proceed to encounter these two sorts of men, and the sort of morality they have given rise to.

2, Masters and Master Morality

Nietzsche makes a distinction between “good and bad” (Gut und Schlecht) and “good and evil” (Gut und Böse) that is peculiar to him. The antithesis “good and bad” is, he theorizes, the older of the two and derives from the standpoint of men he refers to as the “masters” (Herren). “Good and evil” comes later and is the result of the “transvaluation of values” that is effected by those Nietzsche refers to as “slaves” (Sklaven). Nietzsche asks us to imagine the origins of morality in what is, in effect, a struggle between masters and slaves. This is an imaginative reconstruction of events falling outside the historical record, rather like the approach of Rousseau in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men.

You can buy Collin Cleary’s Wagner’s Ring & the Germanic Tradition here.

The more apt comparison, however, is to Hegel, who postulated in his Phenomenology of Spirit that history began with a primal struggle for recognition between Herr (“master” or “lord”) and Knecht (“servant,” often rendered in English translations of Hegel as “slave”). Just as in Nietzsche, these are offered as spiritual types: one is a master in spirit, the other a slave. What distinguishes these? The master type loves honor more than life, whereas the slave type loves life more than honor. Hence, the master is willing to continue the struggle even if it means the loss of his life. The slave is too cowardly to do this, and so at a certain point he yields to the other. The result is that the two then realize in social fact what had before been present only in spirit: the slave becomes a literal slave, and the master his literal master.

It seems like the master has the better deal, but Hegel argues that the aristocratic masters, who scorn labor, allow the slaves to create all of culture for them. The slave sublimates his unsatisfied yearning for recognition into all manner of cultural creations, including a series of intellectual constructions, each of which involves some form of denial of this-worldly existence. “Stoicism” tries to detach itself from the troubles of this world in order to achieve indifference; “skepticism” denies outright the existence of the world; and the “unhappy consciousness” (unglückliche Bewußtsein) yearns for recognition from an extra-worldly, transcendent God. We will see, in fact, that Nietzsche’s analysis of the slave type is not that different from Hegel’s. The path of the Hegelian slave, at least initially, is certainly “life denying,” to use some of Nietzsche’s terminology — though Hegel does not characterize the slave as moved by ressentiment against the masters, as Nietzsche does.

Hegel’s “master-slave dialectic” does not appeal to any sort of historical evidence. And, indeed, given the robust representation of aristocrats among the creators of culture in both the ancient and modern worlds, Hegel’s theory is more than a little wide of the mark. By contrast, Nietzsche appeals to historical examples throughout the text when discussing the character of his own master and slave types. He also utilizes linguistic evidence when dealing with the origins of moral vocabulary — especially with respect to master morality’s distinction between “good and bad.”

Nietzsche writes that

The pathos of nobility and distance, . . . . the continuing and predominant feeling of complete and fundamental superiority of a higher ruling kind in relation to a lower kind, to those “below” — that is the origin of the antithesis “good” and “bad.”[5]

In the conception of the masters, “good” simply describes their own characteristics, whereas “bad” refers to the absence of those characteristics in others. “Noble” and “aristocratic” are the social concepts from which developed the idea of “good,” which initially meant “spiritually noble,” “aristocratic [in bearing and character],” “spiritually high-minded,” or “spiritually privileged.”[6] By contrast “bad” originally referred simply to the “common,” plebeian,” and “low.”[7] Nietzsche credits the modern “democratic bias” with our inability to come to terms with this fact. He writes that

[The] judgment “good” does not emanate from those to whom goodness is shown! Instead it has been “the good” themselves, meaning the noble, the mighty, the high-placed and the high-minded, who saw and judged themselves and their actions as good, I mean first-rate, in contrast to everything lowly, low-minded, common and plebeian.[8]

As we shall see, slave morality is constructed when the slaves react against the masters and declare the traits of the masters “evil,” and their own traits “good.” Master morality, by contrast, does not arise through reaction against another. Instead, Nietzsche tells us that the masters simply “felt” that they were good because they were “complete men,” as he puts it.[9] This intuition of one’s own “goodness” is a matter of physiology. A man who is strong and healthy, who is capable of meeting the challenges of life and of winning in competition against others, has a powerful intuition of his own rightness. This is not a rational judgment, but one that, in effect, a body makes about itself, at a visceral level.[10]

Nietzsche writes that

The chivalric-aristocratic value judgments are based on a powerful physicality, a blossoming, rich, even effervescent good health that includes the things needed to maintain it, war, adventure, hunting, dancing, jousting and everything else that contains strong, free, happy action.[11]

Later, he refers to the masters’ “shocking cheerfulness and depth of delight in all destruction, and all the debauches of victory and cruelty.”[12]

What historical examples is Nietzsche thinking of when he describes the masters? Early in the first essay he mentions the ancient Aryans, whose very name meant “noble.” He later cites “Roman, Arabian, Germanic, Japanese nobility, Homeric heroes, Scandinavian Vikings.” Just prior to this occur some lines that have become notorious:

At the center of all these noble races we cannot fail to see the beast of prey, the magnificent blond beast avidly prowling round for spoil and victory; this hidden center needs release from time to time, the beast must out again, must return to the wild.[13]

A page later he refers to the Goths and Vandals, then to “the raging of the blond Germanic beast.”

These lines have been taken out of context and misinterpreted as signaling Nietzsche’s belief in the superiority of the Nordic race. With the “blond beast,” however, Nietzsche is actually referring to the lion, and his examples of “lion-like” nobles (quoted above) refer to non-Nordics and, indeed, non-Aryans, whom he says are “all alike” with respect to this “hidden center.” (It is just an agreeable coincidence that both ancient Nordic barbarians and lions are blond.) Far from signaling nationalistic pride, Nietzsche immediately follows this by insisting that “between the old Germanic peoples and us Germans there is scarcely an idea in common, let alone a blood relationship.”[14]

3. Slaves and Slave Morality

In historical terms, while it’s clear that Nietzsche’s masters were indeed members of the aristocracy, it’s not clear that his “slaves” were always literal slaves. Certainly, some would have been, but it seems that Nietzsche’s “slaves” could have been anyone in a subservient position vis-à-vis the masters. It is likewise crucial to hold firmly in mind that although Nietzsche’s categories have historical referents, he is also talking about spiritual or psychological “types.” And this means that not everyone in a subservient position counts as a “slave” in Nietzsche’s sense. Indeed, there certainly were literal slaves who would not count as Nietzschean “slaves,” because they did not possess the right (or wrong) sort of soul. Further, the sort of “subservience” meant here is not exclusively social: the slaves for Nietzsche are not just the socially powerless, but the weak and sickly in body and in spirit.

Just to be weak or sickly is not enough, however. Nietzsche’s slave types are principally characterized by the feeling of ressentiment; this is the dominant feature of their psychology. They resent the masters — those they recognize as their betters — and they resent them for their virtues. Ayn Rand, who was influenced by Nietzsche in her younger days, once defined envy as “hatred of the good for being the good” and stated, further, that this means “hatred of that which one regards as good by one’s own (conscious or subconscious) judgment.”[15] This perfectly conveys the essence of ressentiment: the slaves resent the masters not for their faults but precisely for the traits the slaves wish they could possess. Their resentment is thus a kind of tribute paid to the masters.

As noted earlier, while the masters simply intuit that their own traits are good, the morality of the slaves is born in reaction against another. Nietzsche writes:

This reversal of the evaluating glance — this orientation to the outside instead of back onto itself — is a feature of ressentiment: in order to come about, slave morality first has to have an opposing, external world, it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all, — its action is basically a reaction.[16]

Slave morality is born when ressentiment “turns creative,” as Nietzsche puts it, and gives birth to a new set of values. “Whereas all noble morality grows out of a triumphant saying ‘yes’ to itself, slave morality says ‘no’ on principle to everything that is ‘outside,’ ‘other,’ ‘non-self’: and this ‘no’ is its creative deed.”[17] This way of putting things is interesting, for it suggests that the slave is motivated by a kind of primal, negative “egoism.” He is so consumed by the fact that life has handed him a raw deal, he responds to all that is not himself with a kind of nihilating rage. Indeed, he does not just hate the masters; he hates existence itself (a point to which we will return in Part Two, when we discuss the ascetic ideal).

The flip side of the slave’s nihilating rage is a desire to raise himself above all else — not by striving to be better, by transforming his weakness into strength, but by hobbling the strong and condemning strength as such. This is largely the work of those Nietzsche refers to as “the priests” (echoing his earlier text, Thus Spake Zarathustra). He writes that

priests make the most evil enemies — but why? Because they are the most powerless. . . . The greatest haters in world history, and the most intelligent, have always been priests. — nobody else’s intelligence stands a chance against the intelligence of priestly revenge.[18]

This revenge essentially consists in an inversion of values. All that characterized the masters is now declared to be “evil.” For the masters, who arrived at their conception of “good” as an affirmation of their own traits, “bad” was simply “an afterthought.”[19] By contrast, the slaves’ judgment that the masters are “evil,” their reaction against the masters and their characteristics, is the entire basis of slave morality. For the masters, slaves are “bad” just in the sense that fleas and ticks are “bad”: an unfortunate fact of reality, and nothing more. By contrast, “evil” is freighted with assumptions about the supposed “moral responsibility” of the oppressive masters — a point to which we will return in a moment. Nietzsche characterizes the moral inversion perpetrated by the slaves in the following memorable passage:

When the oppressed, the downtrodden, the violated say to each other with the vindictive cunning of powerlessness: “Let us be different from evil people, let us be good! And a good person is anyone who does not rape, who does not harm anyone, who does not attack, who does not retaliate, who leaves the taking of vengeance to God, who keeps hidden as we do, avoids all evil and asks little from life in general, like us who are patient, humble and upright” — this means, if heard coolly and impartially, nothing more than: “We weak people are just weak; it is good to do nothing for which we are not strong enough.”[20]

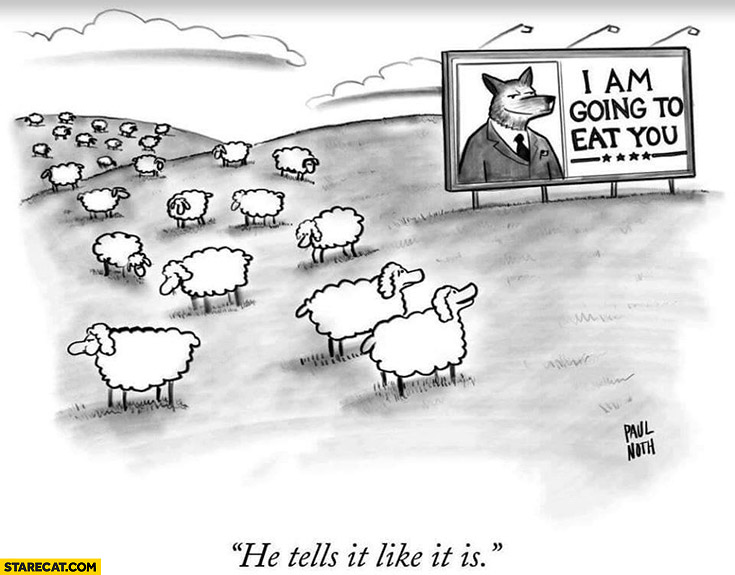

Nietzsche offers a simple parable to explain the situation. Suppose that lambs bore a grudge against the great birds of prey who carry some of them off now and then and devour them. The lambs might say, “These birds of prey are evil; and whoever is least like a bird of prey and most like its opposite, a lamb, — is good isn’t he?”[21] For their part, the birds of prey bear no grudge at all towards the lambs; in fact, they love them, for they are so tender and delicious. It is absurd, of course, to blame the birds of prey for devouring the lambs — as if they could do anything other than act like birds of prey. And this is what Nietzsche says of the masters as well.

In taking such a position, he is rejecting the idea of “free will,” which is the very foundation of the possibility of moral judgment, at least in the dominant moral tradition of our culture. Nietzsche contends, however, that that tradition is the outcome of the slave revolt in morals. In order to judge our own actions, or the actions of another, we assume that the actor could have done otherwise. For example, if I steal I will be condemned — but if it emerges that I was literally forced to steal and could not have acted otherwise, then I am off the hook.

Nietzsche argues that this conception of free will and moral responsibility is a product of slave morality, and that it is a device to hold the masters “responsible.” He writes that

Popular morality separates strength from the manifestations of strength, as though there were an indifferent substratum behind the strong person who had the freedom to manifest strength or not. But there is no such substratum; there is no “being” behind the deed, its effect and what becomes of it; “the doer” is invented as an afterthought, — the doing is everything.[22]

You can buy Collin Cleary’sWhat is a Rune? here

Contrary to what the slaves assert, the strong are not “free” to be weak, any more than the birds of prey are free to be lambs. Needless to say, Nietzsche’s rejection of free will and moral responsibility is an extraordinarily controversial position — one that we cannot fully discuss here, without losing our focus. And our focus is Nietzsche’s psychological analysis of Leftism as a modern-day manifestation of slave morality. It is possible to accept that analysis in most of its details, without committing to Nietzsche’s wholesale rejection of free will.

Nietzsche contrasts master and slave morality on every point. For example, while the slave types are consumed by hatred of their betters, to the point where this hatred essentially defines their very existence, the masters hardly think of the slaves (which may be one reason why the slaves are able to turn the tables on the masters and render what is a product of their own twisted psychology into the dominant moral system). Nietzsche writes:

To be unable to take his enemies, his misfortunes and even his misdeeds seriously for long — that is the sign of strong, rounded natures with a superabundance of a power which is flexible, formative, healing and can make one forget. . . . A man like this shakes from him, with one shrug, many worms that would have burrowed into another man; actual “love of your enemies” is also possible here and here alone — assuming it is possible at all on earth.[23]

I cannot resist the temptation to cite Rand once again, this time her novel The Fountainhead –whose four parts originally opened with epigraphs from Nietzsche, until Rand cut them prior to publication. In one scene late in the book, Howard Roark, the novel’s hero, has a chance meeting with the novel’s villain, Ellsworth Toohey, who is portrayed as an arch purveyor of slave ethics. Toohey says to him, “Mr. Roark, we’re alone here. Why don’t you tell me what you think of me? In any words you wish.” “But I don’t think of you,” Roark responds, and walks away.

Nietzsche also contrasts the differing conceptions of “happiness” held by masters and slaves. Again, he insists that the masters simply “felt” that they were “the happy,” without needing to construct their happiness in reaction against another. Happiness, for the masters, is necessarily tied to a life of action: “they knew they must not separate happiness from action,” Nietzsche says. By contrast, for “the powerless, the oppressed, and those rankled with poisonous and hostile feelings,” happiness is essentially “a narcotic, an anesthetic, rest, peace, ‘sabbath,’ relaxation of the mind and stretching of the limbs, in short something passive.”[24]

In Part Two of this essay, we will deal with Nietzsche’s analysis of the “ascetic ideal,” which contains some of his most important statements about slave morality, and we will deal with his scathing remarks about the Jews. We will then apply Nietzsche’s theories to today’s Left, and discuss recent psychological studies that seem to confirm Nietzsche’s claim that the Left is moved by ressentiment.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.

Notes

[1] Ressentiment is a loan word from French.

[2] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson, trans. Carol Diethe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 8. Unless otherwise noted, all italics in this and other quotations are Nietzsche’s own.

[3] Nietzsche, 8.

[4] Nietzsche, 35.

[5] Nietzsche, 12.

[6] These are Nietzsche’s suggestions. See p. 13.

[7] See also p. 21 for more linguistic examples.

[8] Nietzsche, 11.

[9] Nietzsche, 21.

[10] The only exception to this would be the case of a strong man whose mind has been infected by slave morality, and who thus feels guilt about his natural superiority. (And Nietzsche does believe that slave morality is capable of warping even the strong in spirit.) But when we think of Nietzsche’s master types, we are to imagine men who lived before the advent of slave morality.

[11] Nietzsche, 17.

[12] Nietzsche, 24.

[13] Nietzsche, 23.

[14] Nietzsche, 24.

[15] Ayn Rand, The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution (New York: New American Library, 1975), 153.

[16] Nietzsche, 20.

[17] Nietzsche, 20.

[18] Nietzsche, 17.

[19] Nietzsche, 23.

[20] Nietzsche, 27.

[21] Nietzsche, 26.

[22] Nietzsche, 27.

[23] Nietzsche, 22.

[24] Nietzsche, 21.