Robert Rutherford McCormick, Midwestern Man of the Right: Part 1

2,981 words

Part 1 of 2

The United States has too many ongoing military deployments. There are unnecessary military bases in Syria, Somalia, South Korea, and Niger, to name the most egregious. A solid case can actually be made for the Americans to withdraw from NATO entirely. There have also been a number of pop deployments that have been made to prop up burdensome allies, such as the US Marines’ foray into Lebanon in 1983, to get the Israelis out of a jam they created for themselves.

These deployments are a continuous waste of lives, equipment, and money. In many cases, the nations or peoples being supported are anti-American. They like American money and controllable American politicians, but often hate white Americans. Israelis, for example, enjoy all the American financial aid and weaponry which they use to dispossess the Palestinians and their other neighbors, but Israelis hate white Americans and are especially scornful of the Evangelical Protestants who are their American sine qua non base of support.

A Medill more than a McCormick: Robert McCormick’s background

An American who sought to avoid these problematic foreign entanglements was Robert Rutherford McCormick (1880-1955). McCormick’s patrilineal family originated in Mull, Scotland in the seventeenth century. The McCormick family took part in the plantation of Ulster, and one of Robert’s forbearers served as a Captain at the Siege of Londonderry. Captain McCormick’s children went on to settle in Colonial Pennsylvania. From there they went south to settle in western Virginia, where they prospered. Robert’s great-uncle, Cyrus McCormick, invented the mechanical reaper. The company he founded to make and sell his reaper eventually became International Harvester.

Robert’s maternal grandfather, Joseph Medill, also had Ulster roots, but he was as much Huguenot as Scotch–Irish. Medill’s wife — and Robert’s grandmother — was Katherine Patrick, who was from an old New England/New Amsterdam family. Joseph Medill was raised in Ohio, where he received much of his education from a Quaker tutor. Medill moved to Illinois and became the owner and editor of the Chicago Tribune. Medill was a Republican, an abolitionist, a Unionist, and a supporter of Manifest Destiny. He advocated for the United States to conquer Canada and drive the French out of Mexico in order to leave North America entirely under the control of the American race. During the night of the Chicago Fire, Medill purchased a new printing press as the Tribune’s press and offices burned — and got an edition out the next morning.

As Chicagoans looked at the ashen ruins of their town, Medill’s editorial read:

CHEER UP

In the midst of a calamity without parallel in the world’s history, looking upon the ashes of thirty years’ accumulations, the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN.

Joseph Medill later became Chicago’s Mayor, but his political career was dashed when he alienated part of the Republican Party’s base over saloon taxes. Chicago’s ethic German community liked to drink on Sundays.

The Medill and McCormick families were prominent in the media, industry, the military, and in politics. Robert McCormick’s brother, Joseph McCormick, represented Illinois in the US House and Senate. Ruth Hanna McCormick was a Congresswoman from Illinois as well. They are but a small sample of accomplished individuals from this Midwestern Illinois family.

Joseph Medill (center) makes campaign plans with Abraham Lincoln. Medill was an early member of the Republican Party.

Early career

The McCormick and Medill families where politically at odds in Chicago. Cyrus McCormick was a Southerner and a Democrat. Joseph Medill was a fierce Republican from Ohio. Despite these differences, Medill’s daughter Kate met Robert S. McCormick in the late 1870s. Exactly how Robert S. and Kate met is unknown, as there are several versions of the story. Regardless, the two married, and Robert Rutherford McCormick was born on July 30, 1880.

Robert McCormick’s parents were upper class, but still struggled financially. His father, Robert S. McCormick, lost much of his money in a financial panic. He went on to work for the US State Department and served in several senior diplomatic postings. As a result, Robert moved to England in 1891 and attended an aristocratic school, Ludgrove, the following year. A year later he was sent to Groton, an upper-class boarding school in Massachusetts run by Endicott Peabody, a “puritan” Episcopalian New Englander. Robert attended Groton along with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, although they were in different grades.

McCormick then attended Yale University. Despite being steeped in America’s East-of-the-Hudson WASP culture, he never took to it, remaining a Midwesterner his entire life. He never adopted the internationalist and elitist ideology that was developing in New England at the time.

When McCormick returned to Chicago, he got involved in local politics and was elected as a Republican alderman in 1904. Within months he became President of the Sanitary District Board, where he served for nearly five years.

While he was at the Sanitary District Board, McCormick developed a way to flush the wastewater from the meatpacking factories and associated industries into a sewage system. McCormick was adopting techniques from the most advanced environmental science available at the time. He also worked on improving Chicago in other ways, such as by widening the streets, and he carefully avoided any involvement in corruption.

McCormick would have remained in local politics, but family affairs compelled him to return to the newspaper business. He eventually became the editor of the Chicago Tribune, which was a powerful position.

In a world where everyone receives news instantly on a computer or smartphone, it is difficult to remember how complicated the process of getting a newspaper to its readers was. This required the editor of a major paper to have a business relationship with the lumberjacks who harvested pulpwood, the paper mills, and the transport companies that transported the paper to the printing press and then from the press to the public. McCormick had to deal with labor relations, contracts, industrial processes, and changing input costs all along the line in order to be able to sell a paper that was able to meet its own costs through subscriptions and advertisements. This was further complicated by the fact that rival papers would hire goons to dump copies of the Chicago Tribune into the river. The newspaper business was therefore a lot more than simply writing and editing articles.

The First World War

When the First World War started in the late summer of 1914, McCormick was the established head of a Midwestern media empire. The British government was thus eager to get its message to him. McCormick left for England in February 1915 to report on conditions and met with notable British officials, including Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, and Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. In March 1915 he went to France, where he first experienced being under fire. He found the experience frightening, but muddled through it as best he could.

While in London, he married Amy Irwin Adams. She was the wife of one of McCormick’s cousins, an alcoholic named Ed Adams. Amy was from a family whose men were extremely successful Army officers. After Amy divorced her first husband, she pursued McCormick and married him in London on March 10, 1915. The marriage caused a scandal which McCormick was never able to escape.

You can buy H. L. Mencken’s The Passing of a Profit and Other Forgotten Stories here.

From London, the newlyweds went to Russia with a box of Royal Navy signal flags to present to the Russian Navy. The flags were for Russian-British communication should the upcoming Gallipoli Campaign prove successful. The McCormicks then visited the Carpathian Front in 1915. McCormick filed reports for the Tribune throughout his journey which depicted the Russians in in a heroic and victorious light, but by mid-1915 the Germans had launched an effective counteroffensive which turned out to be the beginning of the end for the Russian Empire.

When he returned to the United States, McCormick joined the 1st Illinois Cavalry (National Guard) and became a Major. He focused on training the men and the horses, anticipating that they would soon have to fight. In his capacity as a newspaper editor, he advocated for preparedness should the United States enter the war, including advocating for the creation of an Army Air Corps.

Prior to the First World War, the United States had received a large influx of European immigrants. Many immigrants merely spent some time working the States before returning to Europe. McCormick had in fact met several Poles in the Russian army in 1915 who had lived in Chicago. As the war clouds gathered, he kept the European immigrant community in mind. He editorialized against Prussian militarism, but was not hostile towards German-Americans in the Midwest. He rightly saw them as assimilating into the American Majority, though he did not use those terms. McCormick viewed the Midwest as a fortress of true Americanism, especially compared to the East Coast.

In March 1916, Poncho Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico. McCormick believed, not irrationally, that the Germans were encouraging border incursions. In response, the 1st Illinois Cavalry was called to active service. McCormick was a Republican partisan and didn’t like Woodrow Wilson, but he supported the administration’s actions along the border. Woodrow Wilson indeed had many faults, but ignoring border security was not one of them.

Robert McCormick was a braggart. In later years, he would claim to have introduced the machine gun into the US Army. This was not strictly true, but he did purchase machine guns for the 1st Illinois Cavalry, which had had no such weapons prior to then. Getting them was not simple, either. All the gun manufacturers in America were working full-time to supply the Europeans with weapons. McCormick thus had to editorialize against “flivver patriotism” to put pressure on the manufacturers to supply the National Guard as well. Five machine guns eventually made it to his regiment. He also affixed a machine gun to a Ford automobile. This was not a first for mechanized firepower, but it was an innovation he brought to the 1st Illinois Cavalry. McCormick’s braggadocio thus ironically diminished his actual accomplishments.

While McCormick’s men didn’t invade Mexico to find Poncho Villa, they did successfully secure the border. Shortly after they returned to Illinois, the Germans introduced their policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. McCormick’s editorials shifted from prepared neutrality to favoring war.

Woodrow Wilson’s policies likewise helped to push America into the British camp. especially when he chose to frame the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania in 1915, which had resulted in the deaths of 123 American civilians, as a German violation of international law, despite the fact that the British were transporting weapons on passenger ships, which was likewise illegal. British intelligence also intercepted and released the Zimmerman Telegram at the beginning of 1917, in which the Germans proposed that the Mexicans should ally with Germany in the event of the US entering the war and invade it with the aim of recapturing the Southwest. The telegram was a crucial step in persuading the initially hesitant American public to support joining the war.

America entered the First World War on April 6, 1917. The question of whether or not this was in fact a good thing to do has never been satisfactorily answered. The Zimmerman Telegram certainly suggests that there was real danger to the United States, so the decision was possibly justified.

After war was declared, the Illinois National Guard, including Robert McCormick’s regiment, was recalled into service. America’s first challenge was getting the various white ethnic groups within its borders to serve together in the military. The Wilson administration used the draft as an opportunity to Americanize immigrants as best as possible. Unlike in the Civil War, there were no ethnic regiments in this conflict. Medal of Honor winner Alvin York was in a squad with two Irishmen, two Italians, and three Polish immigrants, for example.

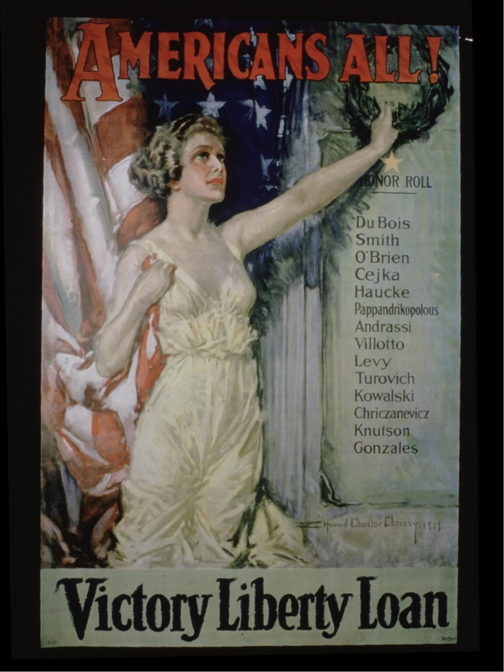

“The draft lists for the American army in the large cities during the World War showed an amazing collection of foreign names. These lists are most dramatic indications of the substantial modifications of the original Anglo-Saxon character of the population which have occurred. A vivid illustration is found in a war poster issued by an enthusiastic clerk of foreign extraction in the Treasury Department during one of the appeals for Liberty Loans. A Howard Chandler Christy girl of pure Nordic type was shown pointing with pride to a list of names, saying ‘Americans All.’” — Madison Grant, The Conquest of a Continent

Americanization’s biggest boost did not come from the military, however. It in fact began to take place when immigration was stopped by the war in 1914, and then stopped again in 1919 as the result of an executive order. It was then reduced to almost nothing in 1924, with the Johnson-Reed Act. Many immigrants likewise returned to Europe, with Swedes, Italians, and Greeks being the most likely to leave.

While Americanization was a problem, the main trouble at home was the oldest one: throughout mobilization, sub-Saharans caused tremendous difficulties. In 1917, members of the 24th US Infantry went on a rampage in Houston; and after the war, Africans went on a crime wave that culminated in the Tulsa Riots of 1921.

It would have been better for all of Western Civilization had the belligerents ceased fighting after Russia fell to the Bolsheviks in 1917. Unfortunately, the nations involved could not seek a compromise once the costs of the war grew so high. Only total victory would satisfy.

The Battle of Cantigny: May 28, 1918

After McCormick was sent to France, he worked in military intelligence on Pershing’s staff, where he rooted out a spy who was transmitting information about American shipping. He later transferred to the field artillery and rose to command the 1st Battalion 5th Field Artillery as a Major. This unit was part of the American 1st Infantry Division, which was organized en route to France and so numbered because it was the first division to arrive. It was also the first American unit to carry out an offensive operation against the Germans, and McCormick played an important role in this.

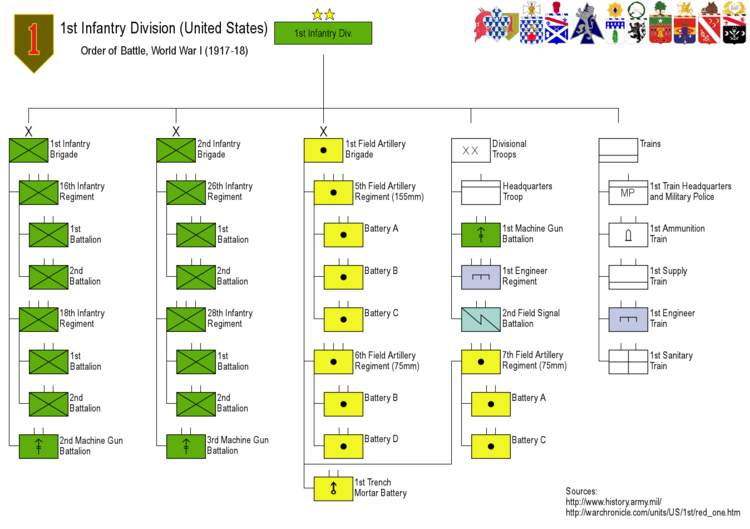

The organization of the 1st Infantry Division. Major McCormick was in the 5th US Field Artillery Regiment.

Shortly after America entered the war, the Germans began an all-out offensive in the hope of overwhelming the French and the British before the Americans could deploy enough troops to make a decisive difference. One of the towns they captured was Cantigny, and the American 1st Infantry was tasked with retaking it.

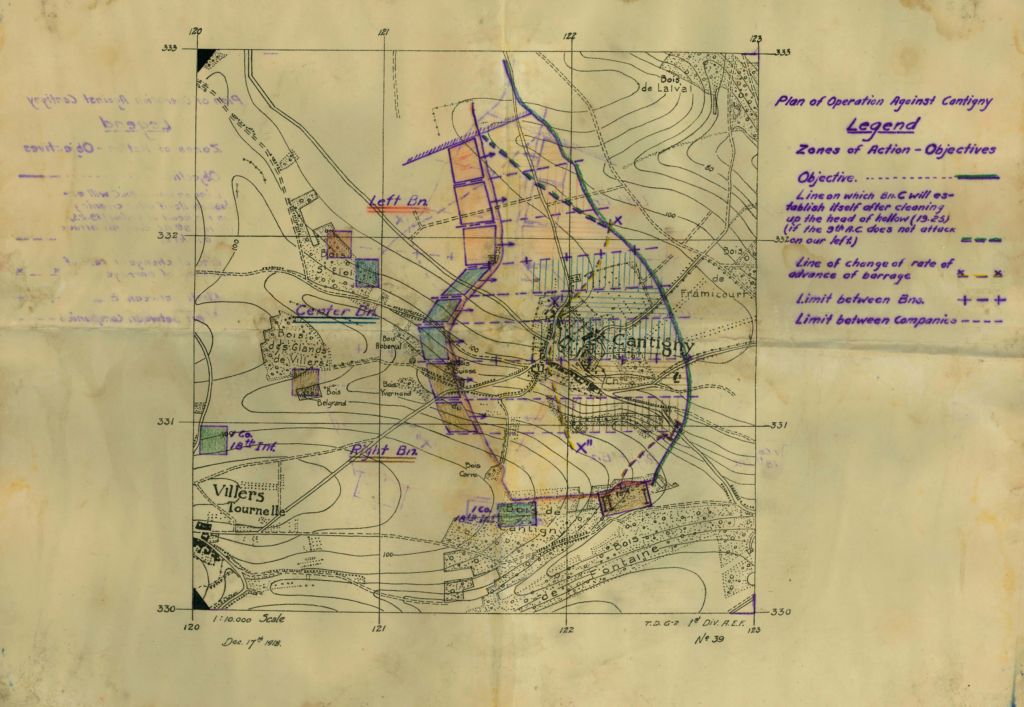

The 1st Infantry Division’s battle plan to recapture Cantigny. The lines across the town indicate where shellfire would be directed during the rolling barrage that would cover their advance. As an artilleryman, Major McCormick was responsible for the barrage.

The attack was to be made by one regiment, the 28th Infantry. The other regiments would either be kept in reserve or would provide supporting fire. The French supplied Schneider tanks, along with three English-speaking French soldiers per tank who were detailed to walk behind them and coordinate with the American infantry needed.

Major McCormick’s job during the battle was to command his battalion of 155mm French-made howitzers and synchronize their fire to support the advancing tanks and infantry. This was carried out by means of a rolling barrage, which is when the artillery is fired at a linear target and the barrage advances according to a pre-planned schedule which attempts to precede and move along with the infantry’s advance. A successful rolling barrage causes the defenders of an enemy position to stay under cover, which allows the attacking infantry to advance without being subjected to enemy fire.

To successfully carry out a rolling barrage, the artillerymen must calculate the range from each cannon to the target such that the shells impact along a line corresponding to the defending force’s positions. The gunners then fire upon that line for as long as they expected their own infantry to advance, and then shift forward along their infantry’s direction of attack. At Cantigny, the artillery began firing on the first line five minutes before the American infantry and its supporting French armor began moving forward. The barrage then advanced 100 meters every two minutes thereafter.

Ammunition management is crucial in a rolling barrage. The shells, fuses, and powder charges must all be in the right place before the shooting starts, and fresh ammunition must be available and moved into position as soon as the initial rounds are exhausted. The soldiers handling the ammunition are every bit as critical as the men in the more prestigious positions on the gun crews. At Cantigny, 200,000 shells were delivered under the cover of darkness just before the battle on May 28, 1918. The attack was a success, and the town was taken in only half an hour.

Major McCormick was greatly aided by his soldiers’ professionalism. The commander of the 1st Field Artillery Brigade was Brigadier General Charles Summerall. His staff developed the plan for the attack, and McCormick carried it out. His ability to work well with others and recognize their expertise were great assets.

McCormick never stopped being a newspaper man during the war. He contributed to the Chicago Tribune every chance he could. After Cantigny, McCormick was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was then transferred to the 122nd Field Artillery. After serving in that regiment for several months, he was promoted to Colonel and sent back to Fort Sheridan, Illinois to command the 61st Field Artillery during training in preparation for the anticipated campaigns of 1919, but the war ended before their training was complete. The biggest crisis the 61st Field Artillery ended up facing was the Spanish Flu, where men who were perfectly healthy could end up dead by afternoon. McCormick was released from active duty with the cessation of hostilities, but he remained in the reserves for the next decade.

* * *

Like all journals of dissident ideas, Counter-Currents depends on the support of readers like you. Help us compete with the censors of the Left and the violent accelerationists of the Right with a donation today. (The easiest way to help is with an e-check donation. All you need is your checkbook.)

For other ways to donate, click here.